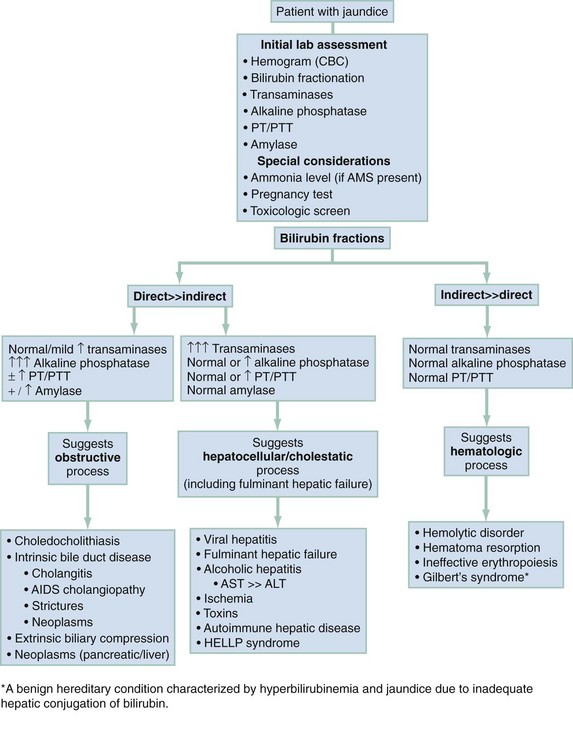

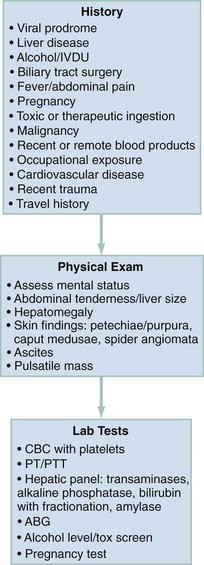

Chapter 28 The three major diagnostic categories to consider are liver injury or dysfunction (cholestasis), biliary obstructive disorders, and disorders of hemolysis. Figure 28-1 outlines a laboratory-based approach to differentiating among these three categories. The pivotal findings related to history, physical examination, and ancillary testing are listed in Figure 28-2. Pertinent physical examination findings are summarized in Figure 28-2. Examination of the skin and the abdomen is particularly helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Neurologic examination of the jaundiced patient may show depressed mental status, indicating hepatic encephalopathy or cerebral dysfunction caused by sepsis. Asterixis is a specific finding of hepatic encephalopathy. Table 28-1 addresses the clinical stages of hepatic encephalopathy. Table 28-1 Clinical Stages of Hepatic Encephalopathy From Fitz G: Systemic complications of liver disease. In Feldman M, Sleisenger M, eds: Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998. Figure 28-2 lists the laboratory tests that are helpful in the evaluation of a patient with jaundice. Serum γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) rises in parallel with alkaline phosphatase (AP) in the setting of liver disease.1 Although AP also can be elevated in diseases affecting bone or placenta, the concomitant increase in serum GGT or 5′-nucleotidase confirms a hepatic source. A reticulocyte count and evaluation of the peripheral blood smear may identify hemolysis. In cases of unexplained hepatocellular injury, a quantitative acetaminophen level may be helpful. Bedside stool guaiac testing assesses for the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Both glucose and ammonia metabolism can be altered in the presence of hepatocellular injury, and patients with altered mental status should have glucose and ammonia levels determined. The degree of elevation in serum ammonia does not correlate directly with the level of hepatic encephalopathy. Ascitic fluid should be analyzed in patients with new-onset ascites and in those with established ascites but new complaints of fever, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, hypotension, or renal failure. Cell count and differential, albumin, and total protein concentration are sufficient initial screening tests. In the setting of suspected bacterial peritonitis, fluid culture is also necessary; Gram stain is rarely helpful. Two sets of blood cultures should be performed for patients with fever and jaundice. If there is evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding with hemodynamic instability or severe anemia, a type and crossmatch should be performed by the laboratory.

Jaundice

Diagnostic Approach

Pivotal Findings

Signs

CLINICAL STAGE

INTELLECTUAL FUNCTION

NEUROMUSCULAR FUNCTION

Subclinical

Normal examination findings, but work or driving may be impaired

Subtle changes in psychometric testing

Stage 1

Impaired attention, irritability, depression, or personality changes

Tremor, incoordination, apraxia

Stage 2

Drowsiness, behavioral changes, poor memory, disturbed sleep

Asterixis, slowed or slurred speech, ataxia

Stage 3

Confusion, disorientation, somnolence, amnesia

Hypoactive reflexes, nystagmus, clonus, muscular rigidity

Stage 4

Stupor and coma

Dilated pupils and decerebrate posturing; oculocephalic reflex

Laboratory Tests

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Jaundice

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue