Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is the preferred method of emergency airway management. It involves the near simultaneous administration of fast-acting induction and neuromuscular blocking agents to achieve optimal intubating conditions without the need for bag-mask ventilation. The following discussion of orotracheal intubation refers to RSI. Techniques for gum-elastic bougie insertion and nasotracheal intubation are also discussed.

INDICATIONS

![]() Failure to protect the airway

Failure to protect the airway

![]() Failure to maintain the airway

Failure to maintain the airway

![]() Failure of ventilation

Failure of ventilation

![]() Failure of oxygenation

Failure of oxygenation

![]() Predicted deterioration or anticipated clinical course requiring intubation

Predicted deterioration or anticipated clinical course requiring intubation

CONTRAINDICATIONS

![]() Orotracheal and Nasotracheal Intubation

Orotracheal and Nasotracheal Intubation

![]() Total upper airway obstruction

Total upper airway obstruction

![]() Total loss of facial landmarks

Total loss of facial landmarks

![]() Nasotracheal Intubation

Nasotracheal Intubation

![]() Apnea

Apnea

![]() Basilar skull or facial fracture

Basilar skull or facial fracture

![]() Neck trauma or cervical spine injury

Neck trauma or cervical spine injury

![]() Head injury with suspected increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

Head injury with suspected increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

![]() Nasal or nasopharyngeal obstruction

Nasal or nasopharyngeal obstruction

![]() Combative patients or patients in extremis

Combative patients or patients in extremis

![]() Coagulopathy

Coagulopathy

![]() Pediatric patients

Pediatric patients

LANDMARKS

![]() Viewing the oropharynx from above, the tongue is the most anterior structure

Viewing the oropharynx from above, the tongue is the most anterior structure

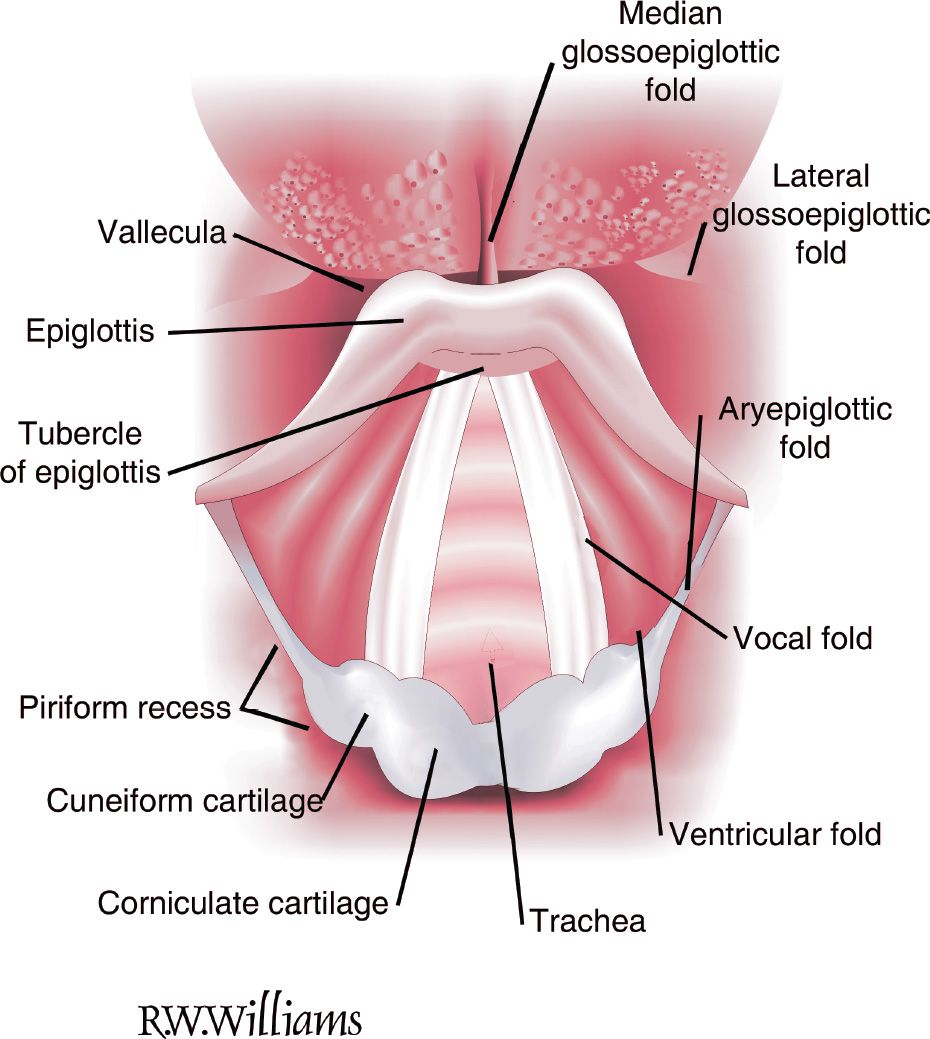

![]() The pouchlike vallecula separates the tongue from the epiglottis, which sits above the larynx (FIGURE 1.1)

The pouchlike vallecula separates the tongue from the epiglottis, which sits above the larynx (FIGURE 1.1)

![]() The vocal cords sit as an inverted “V” within the larynx

The vocal cords sit as an inverted “V” within the larynx

![]() The larynx is anterior to the esophagus

The larynx is anterior to the esophagus

TECHNIQUE FOR OROTRACHEAL INTUBATION

![]() General Basic Steps

General Basic Steps

![]() Preparation

Preparation

![]() Preoxygenation

Preoxygenation

![]() Pretreatment

Pretreatment

![]() Paralysis and induction

Paralysis and induction

![]() Positioning

Positioning

![]() Placement of tube

Placement of tube

![]() Proof of placement

Proof of placement

![]() Postintubation management

Postintubation management

FIGURE 1.1 Larynx visualized from the oropharynx. Note the median glossoepiglottic fold. It is pressure on this structure by the tip of a curved blade that flips the epiglottis forward, exposing the glottis during laryngoscopy. Note that the valleculae and the pyriform recesses are different structures, a fact often confused in the anesthesia literature. The cuneiform and corniculate cartilages are called the arytenoid cartilages. The ridge between them posteriorly is called the posterior commissure. (Reused with permission from Redden RJ. Anatomic considerations in anesthesia. In: Hagberg CA, ed. Handbook of Difficult Airway Management. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:9.)

![]() Preparation

Preparation

![]() Assess airway: Use LEMON mnemonic to predict difficulty of airway

Assess airway: Use LEMON mnemonic to predict difficulty of airway

![]() Look externally: If you sense that an airway appears difficult, it likely is

Look externally: If you sense that an airway appears difficult, it likely is

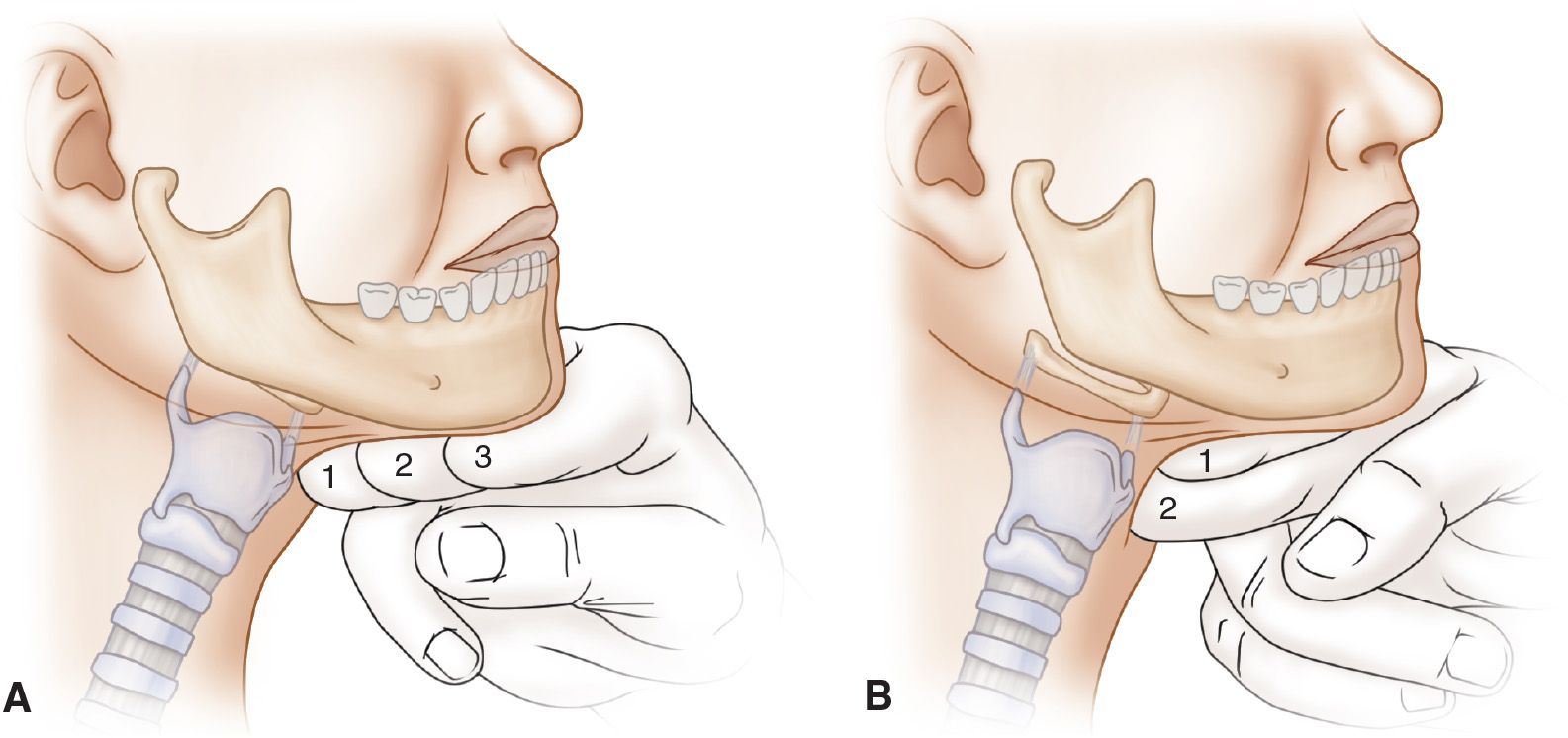

![]() Evaluate anatomy: The “3-3-2 rule” (FIGURE 1.2)

Evaluate anatomy: The “3-3-2 rule” (FIGURE 1.2)

![]() Thyromental distance: Should be approximately 3 finger widths. Significantly more or less suggests a difficult airway.

Thyromental distance: Should be approximately 3 finger widths. Significantly more or less suggests a difficult airway.

![]() Mouth opening: Less than 3 finger widths predicts poor visualization on laryngoscopy and a difficult airway

Mouth opening: Less than 3 finger widths predicts poor visualization on laryngoscopy and a difficult airway

![]() Hyomental distance: More or less than 2 finger widths predicts a difficult airway

Hyomental distance: More or less than 2 finger widths predicts a difficult airway

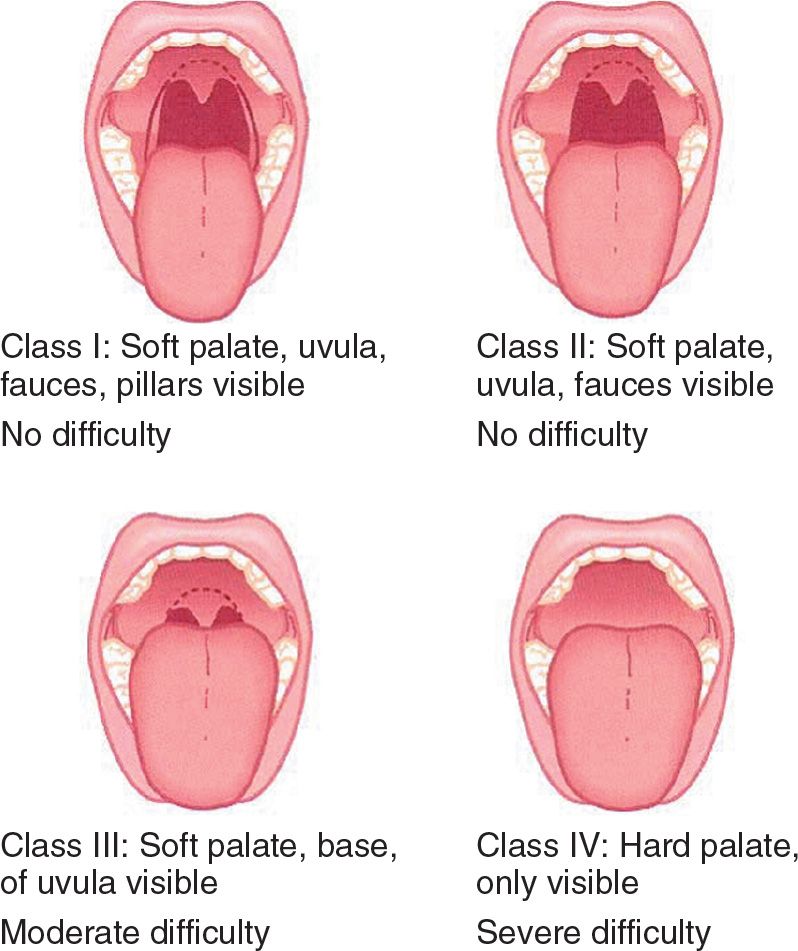

![]() Mallampati score: Roughly correlates the view of internal oropharyngeal structures with intubation success. Graded as class I to IV (FIGURE 1.3).

Mallampati score: Roughly correlates the view of internal oropharyngeal structures with intubation success. Graded as class I to IV (FIGURE 1.3).

![]() Obstruction/Obesity: Any evidence of upper airway obstruction heralds a difficult airway. Obesity is also associated with difficult laryngoscopy.

Obstruction/Obesity: Any evidence of upper airway obstruction heralds a difficult airway. Obesity is also associated with difficult laryngoscopy.

![]() Neck mobility: Crucial to obtaining the optimum view of the larynx. Hindrance to neck extension, including cervical spine immobilization, predicts difficulty in intubation.

Neck mobility: Crucial to obtaining the optimum view of the larynx. Hindrance to neck extension, including cervical spine immobilization, predicts difficulty in intubation.

![]() Equipment

Equipment

![]() Endotracheal tube (ETT) and smaller backup (often 7.5 or 8.0 and 7.0)

Endotracheal tube (ETT) and smaller backup (often 7.5 or 8.0 and 7.0)

![]() 10-cc syringe

10-cc syringe

![]() Laryngoscope blade

Laryngoscope blade

![]() Laryngoscope handle

Laryngoscope handle

![]() Suction

Suction

![]() Rescue airway devices, including oral airway, gum-elastic bougie, and laryngeal mask airway

Rescue airway devices, including oral airway, gum-elastic bougie, and laryngeal mask airway

![]() RSI pharmacologic agents

RSI pharmacologic agents

FIGURE 1.2 A: The second 3 of the 3-3-2 rule. B: The 2 of the 3-3-2 rule. (From Walls RM, Murphy MF. Manual of Emergency Airway Management. The 4th edition, 2012 version of the Walls Emergency Manual as well. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:77, with permission.)

![]() Check integrity of ETT cuff

Check integrity of ETT cuff

![]() Ensure that laryngoscope light source is working properly

Ensure that laryngoscope light source is working properly

![]() Make sure IV is functioning

Make sure IV is functioning

![]() Ensure patient is appropriately monitored

Ensure patient is appropriately monitored

![]() Position patient and adjust bed height

Position patient and adjust bed height

![]() Assign team roles

Assign team roles

![]() Prepare for possible surgical airway

Prepare for possible surgical airway

![]() Preoxygenation

Preoxygenation

![]() Theoretically, deliver 100% oxygen for 3 minutes via nonrebreather mask. (In reality, it delivers approximately 70% oxygen.)

Theoretically, deliver 100% oxygen for 3 minutes via nonrebreather mask. (In reality, it delivers approximately 70% oxygen.)

![]() This fills the functional residual capacity with oxygen, replacing nitrogen and allowing for a longer apneic period before desaturation

This fills the functional residual capacity with oxygen, replacing nitrogen and allowing for a longer apneic period before desaturation

![]() When time is critical, preoxygenation can be achieved in eight vital capacity breaths

When time is critical, preoxygenation can be achieved in eight vital capacity breaths

![]() Nasal cannula should be placed to augment preoxygenation and facilitate apneic oxygenation

Nasal cannula should be placed to augment preoxygenation and facilitate apneic oxygenation

![]() Pretreatment

Pretreatment

This refers to the administration of medications to attenuate the potential adverse side effects of intubation. Medications are given 3 minutes prior to intubation. While evidence supporting pretreatment is not conclusive, it should be considered in the following groups of patients:

![]() Elevated ICP: To mitigate ICP increase with laryngoscopy and intubation

Elevated ICP: To mitigate ICP increase with laryngoscopy and intubation

![]() Lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg

Lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg

![]() Fentanyl 3 μg/kg

Fentanyl 3 μg/kg

![]() Cardiovascular disease: To decrease sympathetic response

Cardiovascular disease: To decrease sympathetic response

![]() Fentanyl 3 μg/kg

Fentanyl 3 μg/kg

![]() Reactive airway disease: To reduce bronchospasm

Reactive airway disease: To reduce bronchospasm

![]() Lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg

Lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg

![]() Albuterol 2.5 mg nebulized

Albuterol 2.5 mg nebulized

![]() Paralysis and Induction

Paralysis and Induction

![]() Give the induction agent, as a bolus, in sufficient dose to produce immediate loss of consciousness. Common agents are propofol (1.5–3 mg/kg) and etomidate (0.3 mg/kg).

Give the induction agent, as a bolus, in sufficient dose to produce immediate loss of consciousness. Common agents are propofol (1.5–3 mg/kg) and etomidate (0.3 mg/kg).

![]() Push the paralytic agent immediately following the induction agent. Succinylcholine (1.5–2 mg/kg) is the common first choice in RSI because of its rapid onset.

Push the paralytic agent immediately following the induction agent. Succinylcholine (1.5–2 mg/kg) is the common first choice in RSI because of its rapid onset.

![]() Fasciculations will occur 20 to 30 seconds after the administration of succinylcholine

Fasciculations will occur 20 to 30 seconds after the administration of succinylcholine

![]() Apnea and paralysis will occur almost uniformly by 1 minute

Apnea and paralysis will occur almost uniformly by 1 minute

FIGURE 1.3 The Mallampati Scale. (From Walls RM, Murphy MF. Manual of Emergency Airway Management. 4th edition, 2012 version of the Walls Emergency Manual as well. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:78, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree