INTRODUCTION

INTRAOSSEOUS ACCESS

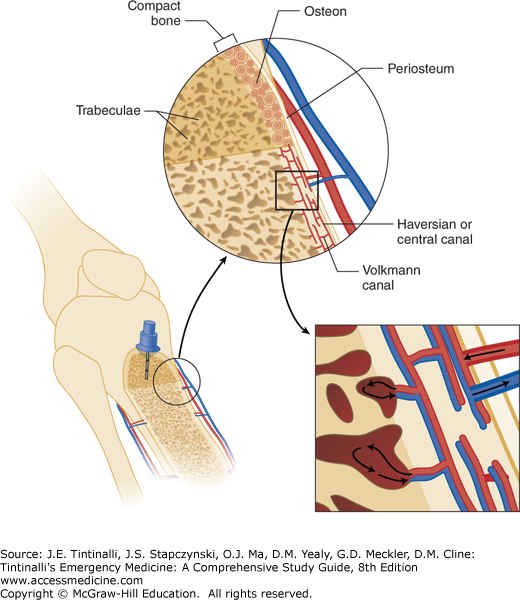

Intraosseous access has the advantage of cannulating a noncollapsible structure that connects to the central circulation. The intraosseous approach is particularly useful for children as a result of their high percentage of red bone marrow and relatively thin bony cortex.

Intraosseous access is indicated when there is an emergent need for vascular access and other sites are difficult, high risk, or excessively time-consuming. Mechanical intraosseous insertion devices have insertion times of only seconds with consistently >90% success rates.1,2,3,4,5,6 Insertion devices include simple hand-twist needles, hand-held power drills, and spring-loaded devices.

There are few contraindications to intraosseous placement (Table 112-1), and the rate of serious complications from intraosseous insertion is ≤1%. The most common complication is extravasation at the insertion site. By comparison, central venous catheters have complication rates of at least 3.4%.7,8

Any medication or fluid that can be given through an IV can be administered by the intraosseous route. Paralytics, anticonvulsants, analgesics, benzodiazepines, and vasopressors such as epinephrine have comparable intraosseous and IV infusion rates. Blood and blood products can be given by the intraosseous route.9 Medications for rapid-sequence intubation can be administered by the intraosseous route, although the time to effect may be delayed.10 In a study of sheep given IV or intraosseous succinylcholine, the IV route induced respiratory arrest in a mean of 30.8 seconds, whereas the intraosseous route took 57.5 seconds.11

The principal limitation of intraosseous access is a relatively low maximum flow rate. Resistance to flow within the bone marrow cavity limits the flow rate of intraosseous needles, and flow rates per kilogram tend to be higher in young patients who have a greater percentage of low-resistance red marrow compared to adults. The speed of administration of intraosseous infusions can be improved with pressure devices.

The comparison of marrow aspirate with peripheral blood has been explored in small trials of hematology and oncology patients undergoing routine marrow sampling (Table 112-2). Two of these human studies have shown a close correlation of marrow aspirate to venous blood in regard to hemoglobin, sodium, chloride, bilirubin, pH, bicarbonate, urea, and creatinine concentrations.12,13 In another study, bone marrow taken for medical diagnosis correlated with the peripheral blood for ABO, Rh typing, and leukocyte activity.14 Correlation between bone marrow and peripheral blood is less reliable for leukocytes, platelets, glucose, potassium, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, and partial pressure of oxygen; however, the degree of discrepancy likely has minimal clinical significance. Aspirates obtained from the marrow after prolonged CPR may be considerably different from serum levels.15

| Equivalent | Use Caution in Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | Hemoglobin | Leukocytes, hematocrit, platelets |

| Chemistries | Sodium, chloride, glucose, bilirubin, bicarbonate, urea, and creatinine | Potassium, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase |

| Venous gas | pH | PCO2, PO2 |

| Transfusion | ABO, Rh typing, and leukocyte activity | — |

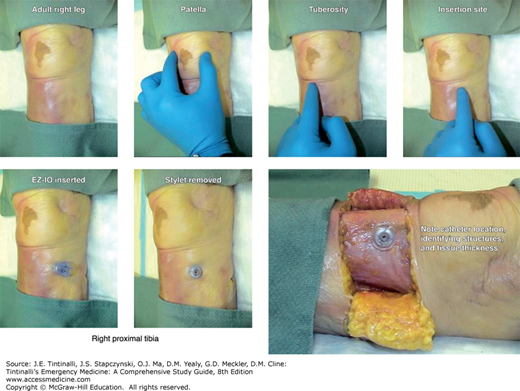

There are several devices available for intraosseous insertion. The two most common manual insertion devices include the Cook® intraosseous needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) and the Jamshidi® style intraosseous needles. Powered devices are also available for intraosseous needle insertion; two examples are the EZ-IO® (Vidacare Corp., San Antonio, TX) and the Bone Injection Gun (BIG®) (Waismed, Ltd., Hertzliya, Israel). There is one prospective randomized study comparing manual to powered insertion devices in pediatrics in the prehospital setting, which compared the Jamshidi needle to the BIG. There were only 22 children in the cohort, which was primarily comprised of adults. There were no significant differences in time to insertion, which was less than 1 minute for both devices, or success rate, which was approximately 80% for both devices.4 Several studies have demonstrated rapid insertion and high success rates (>90%) using the EZ-IO in children, even among providers with minimal training.4,16 Small randomized studies in adults comparing the EZ-IO to the BIG suggest faster time to insertion and a higher first-time insertion success rate for the EZ-IO.5,6 The EZ-IO is a battery-powered cordless drill with a specialized needle (Figure 112-1). The needle is chosen based on the patient’s weight and the distance from the skin to the bone (Figure 112-2). This device is intended for use in the proximal tibia, distal tibia, or proximal humerus. The BIG is a spring-loaded device that can be used in the proximal tibia; the pediatric device allows adjustable depths of insertion based on the patient’s age. The BIG has the potential to cause injury to patient or provider if fired at the wrong time.

FIGURE 112-2.

EZ-IO® needle sizes. The pink needle set is 15 mm in length (EZ-IO PD). This size is used in most children. The blue needle set is adult sized at 25 mm in length (EZ-IO AD), and the yellow needle set is for larger adults and is 45 mm in length (EZ-IO LD). The length and color are the only differences between needle sets. [Reproduced with permission from Vidacare Corp., San Antonio, TX. For updates see http://www.vidacare.com/ez-io/index.html.]

The ideal location for intraosseous access is a large bone with easily palpable landmarks, a thin cortex, and limited proximity to vital structures. The proximal or distal tibia, distal femur, and sternum are the sites most commonly described. The flat surface of the anteromedial proximal tibia is easily accessible given the paucity of overlying tissue, making it the most commonly accessed site (Figure 112-3).16 Insert the needle 2 cm inferior (distal) to the tibial tuberosity to avoid the physeal plate in children (Figure 112-4). When accessing the distal tibia, enter just superior to the medial malleolus, avoiding the saphenous vein (Figure 112-5), which is located 2 cm anterior and 2 cm superior to the malleolus. In adults, the distal tibia has thinner cortex than that of the proximal tibia. The anterior distal femur is an alternate site for children when the proximal tibia cannot be used or has failed (Figure 112-6). Insert the needle two fingerbreadths superior (proximal) to the distal end of the femur in the midline.