Fig. 34.1

Early would infection, localized to the intrathecal pump pocket with small dehiscence and purulent drainage 2 weeks after initial placement. Image from Dr. Malik personal library

34.4 Clinical Manifestation of IDDS Infections

- 1.

Classification of surgical site infections (SSIs). The CDC classifies SSIs as either incisional, which is subdivided into those involving only the skin or subcutaneous tissue or those involving deeper soft tissues, or organ/space. Organ/space SSIs involve any part of the surgical anatomy other than the body wall layers [6]:

- (a)

Superficial incisional SSI . This infection occurs within 30 days after the operation and involves only the skin or subcutaneous tissue. Classical signs of infection must be present on exam such as localized tenderness, swelling, warmth, or erythema. Purulent drainage from the incisional site may also be present [6].

- (b)

Deep incisional SSI . This infection occurs within 30 days after the operation or within 1 year if implant is in place and the infection appears to be related to the operation and infection involves deep soft tissues. It will manifest as purulent drainage from the deep incisional layers, as spontaneous dehiscence of a wound in a patient with classical signs of infection on examination in the presence of a fever, or as an abscess or other signs of a deep infection noted on examination, during reoperation, or on radiologic examination [6].

- (c)

Organ/space SSI . This infection occurs within 30 days after the operation or within 1 year if implant is in place and the infection appears to be related to the operation. The infection must involve any part of the organs or spaces that were manipulated during an operation. Finally, there must be present either purulent drainage from a drain in the organ space, an organism isolated from tissue or fluid in the organ/space, or evidence of infection involving the organ/space seen during reoperation or on radiographic examination [6].

- (a)

- 2.

Bacterial meningitis. Bacterial meningitis can present with the classic triad of fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status. However, a recent study found the prevalence of this classical presentation to be low, but almost all patients (95%) presented with at least two of four symptoms of headache, fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status [7]. Other neurologic findings such as seizures, papilledema, and cranial nerve abnormalities can be present as well but typically present later in the course of the disease [7, 8].

- 3.

Bacterial encephalitis. It presents in a similar fashion as bacterial meningitis. Focal neurological deficits and seizures may be more prominent with encephalitis when compared to meningitis [9]. The most common pathogens resulting in encephalitis are viruses, but when the pathogen is bacterial in nature, meningeal signs are typically more prominent than the ones in viral encephalitic component, and as a whole it is typically referred to as meningoencephalitis [9].

34.5 Specific Diagnostic Methods

- 1.

Blood samples. Once there is suspicion for IDDS-associated infection, blood samples should be sent for a complete blood cell count, which should demonstrate a polymorphonuclear leukocytosis (PMN) with a left shift. Blood samples should also be sent for gram stain and culture. Ideally, blood cultures are sent prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy in order to have a higher success at identifying the pathogen [10]. Serum electrolytes should be evaluated in order to obtain renal function and serum glucose.

- 2.

Tissue cultures. In cases that have an open and draining wound, fluid and wound samples should be sent for gram stain and culture. Ideally these samples would be sent prior to initiation of antibiotic therapy in order to have the highest likelihood of identifying the infectious pathogen.

- 3.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples. Lumbar puncture (LP) should be performed once there is suspicion for bacterial meningitis or encephalitis. The opening pressure is usually elevated in the 20–50 cm H2O range and may be turbid in appearance due to increased white blood cells (WBC) and bacteria [10]. The WBC will have a PMN predominance, and CSF studies for glucose and protein will show a low glucose concentration and elevated protein concentration. CSF samples should also be sent for gram stain and culture. The likelihood that the gram stain will identify the pathogen depends on the bacteria responsible and ranges between 33 and 90%. This likelihood drops by about 20% in patients who receive antibiotic therapy prior to obtaining CSF [10].

- 4.

Radiographic studies:

- (a)

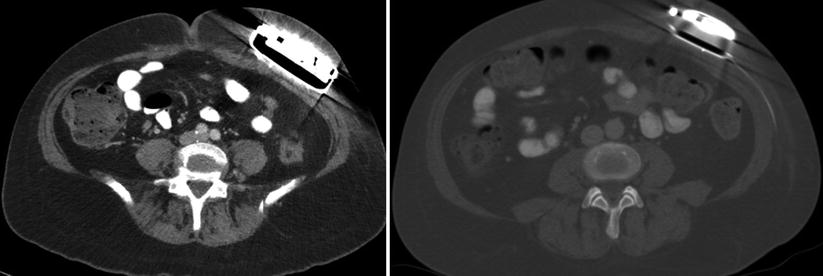

CT scan. CT scan of the pump pocket would be of little benefit due to metal artifact seen on the image. Sometimes, in associated cellulitis, fat strained can be present (Fig. 34.2) A contrast-enhanced cranial CT scan may reveal changes consistent with bacterial meningitis or encephalitis but is not necessary for establishing a diagnosis. These changes would be noted as diffuse enhancement of the subarachnoid space as well as dural enhancement [12]. However, a cranial CT scan is most useful in detecting contraindications to lumbar puncture [11].

- (b)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) . Cranial MRI is more useful in identifying meningeal enhancement that is consistent with meningitis; however, it is again not necessary establishing a diagnosis and is a non-specific finding seen in other disorders involving the central nervous system [12]. MRI is also useful in identifying soft tissue changes consistent with surgical site infection as well as identifying an epidural abscess that might be associated with the infection [13].

- (c)

Ultrasound. Ultrasound has no utility in diagnosing bacterial meningitis. However, it can be used to identify fluid-filled pockets associated with soft tissue infections [14].

- (a)

Fig. 34.2

Patient with delayed infection at the pump pocket. Despite significant artifact, both images show fat stranding consistent with cellulitis. The concern was tracking of the fat stranding toward the spine in image 2. The images are taken 6 months apart. First episode of cellulitis was treated with intravenous antibiotics and temporarily resolved the symptoms; pump was eventually explanted. Image from Dr. Anitescu personal library

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree