INJURY: KNEE

MARC N. BASKIN, MD AND CYNTHIA M. ADAMS, MD

Acute pain or injury to the knee is a common complaint in the emergency department (ED). Many injuries are minor and require only limited therapy; others, however, require consultation with an orthopedist, either in the ED or as outpatients after pain and inflammation subside. The emergency physician can provide appropriate therapy or determine the need for consultation, based on a comprehensive history, physical examination, and an appropriate radiographic evaluation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

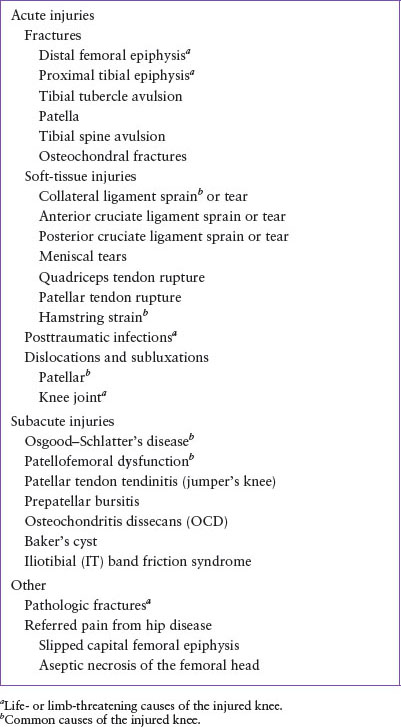

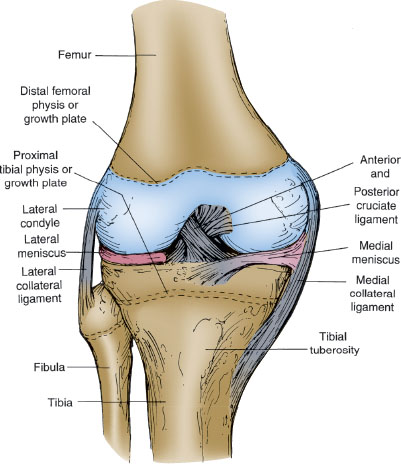

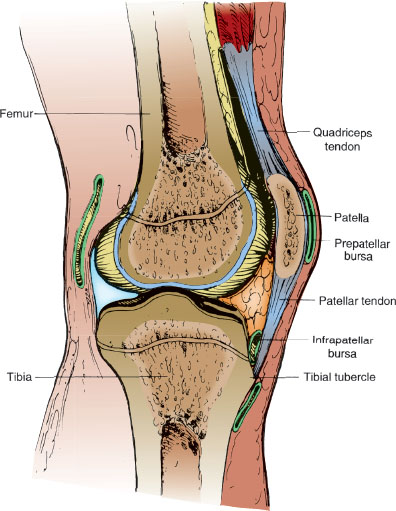

The differential diagnosis of acute and chronic knee injuries is summarized in Table 37.1. The pertinent anatomy is illustrated in Figures 37.1 and 37.2.

Acute Injuries

Fractures

Preadolescents with open growth plates (physes) are especially susceptible to fractures. Since pediatric bone strength is less than pediatric ligament strength, an injury that would cause a ligamentous injury in adults may cause a Salter–Harris type physeal fracture in children. For bones around the knee, the epiphyses close by 17±1 years in females and by 18±1 years in males.

Fractures of the distal femoral epiphysis are classified by the Salter–Harris pattern (see Chapter 119 Musculoskeletal Trauma) and by the displacement of the epiphysis (usually lateral or medial). The injury usually follows significant trauma (e.g., being struck by a car and the knee hyperextended or during contact sports when sustaining a lateral hit with the foot fixed by cleats). Distal neurovascular status should be assessed because compromise of the popliteal artery occurs in 1% of cases and peroneal nerve injury occurs in 3% of cases.

Fractures of the proximal tibial epiphysis are rarer than those of the distal femoral epiphysis but are more likely to involve vascular compromise because of the proximity of the popliteal artery to the posterior aspect of the tibial epiphysis. With both fracture types, the patient will have severe pain, refusal to bear weight, extensive soft-tissue swelling, limited range of motion (ROM), and commonly, hemarthrosis. For both injuries, radiographs are usually diagnostic but may be normal if the injury is a nondisplaced Salter–Harris type I fracture. Although not necessary as part of ED evaluation, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be needed when the physis is tender or a large effusion is present.

Acute traumatic avulsion of the tibial tuberosity is caused by acute stress on the knee’s extensor mechanism. The quadriceps muscle group extends the knee by way of the patellar ligament. The patellar ligament inserts on the tibial tuberosity and may avulse it during sudden acceleration (e.g., beginning a jump) or deceleration (e.g., landing after a jump). The patient will have tenderness and swelling over the tibial tubercle and be unable to extend the knee fully (or perform a straight leg raise). A lateral radiograph is diagnostic.

Fractures of the patella are rare in younger children because the child’s patella does not ossify until 3 to 6 years of age, leaving it with a thick cartilage layer that protects it from direct trauma. In addition, the soft tissue anchors of the patella are flexible which diffuses blunt forces. However, a direct impact on the patella into the distal femur can cause transverse or comminuted fractures. Much more common in children are avulsion fractures of the patella resulting from forceful contraction of the quadriceps. With patellar fractures, the patient’s knee will be swollen, the patella tender, and knee extension painful. A radiograph is usually diagnostic although care must be taken not to miss small avulsion fragments including sleeve fractures which are unique to pediatrics (egg-shell–like bony fragment that dislocates with avulsed soft tissue). Bipartite patellas are a normal variant and may be confused with an acute fracture.

Osteochondral fractures are fractures of articular cartilage and underlying bone not associated with ligamentous attachments. These fractures often involve the femoral condyles or the patella. The injury may follow a direct blow to the knee, a twisting injury, or patellar dislocation. The patient will have severe pain, immediate swelling, and will hold the knee partially flexed. Hemarthrosis may be present. Knee radiographs need to include an intercondylar view because the fracture fragment may be in the intercondylar notch. Osteochondral fractures can be missed because only the small ossified portion of the osteochondral fragment is radiopaque. MRI may be necessary.

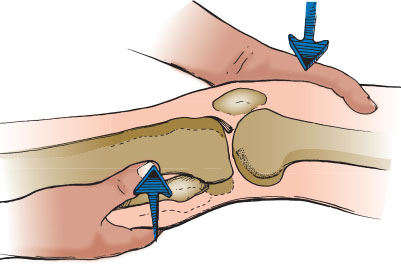

Analogous to an adolescent who ruptures the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), patients 6 to 16 years old may sustain avulsion fractures of the tibial spine at the point where the ACL inserts. The tibial spine is incompletely ossified and may avulse before the ligament ruptures. The patient may have a hemarthrosis and will be unable to bear weight. If the patient tolerates an examination, the Lachman test (see Fig. 37.3) may be positive because the injury is similar mechanically to an ACL tear. AP, lateral, and intercondylar or tunnel-view radiographs will show the avulsed fragment. The visible ossified fragment may be small because the tibial spine is mostly radiolucent cartilage.

Dislocations

In a child, the knee joint itself rarely dislocates; usually, the distal femoral or proximal tibial epiphysis separates first. Dislocation occurs more frequently when the growth plates have closed and usually with trauma that involves significant force, such as a motor vehicle collision or contact sports. The knee will appear obviously deformed with the tibia or femoral condyles abnormally prominent in an anterior or posterior dislocation, respectively. Disruption of the popliteal artery may occur with the dislocation, and the resulting hypoperfusion may be limb threatening. Posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses and peroneal nerve function (sensation between the great and second toe and ankle dorsiflexion) must be documented. Radiographs will confirm the diagnosis.

TABLE 37.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF THE INJURED KNEE

Patellar dislocation occurs as the quadriceps muscles pull the patellar tendon to extend the knee, especially when the knee has a valgus stress or the extremity is suddenly abducted as when the leg slips laterally. If the vastus medialis fibers do not keep the patella in the intercondylar groove, the patella may dislocate laterally. This often recurrent injury rarely occurs from direct force. The patient may feel a popping sensation and will have intense pain and hold the knee flexed. The patella is displaced laterally, and the diagnosis is usually made based on history and examination. The dislocation may be reduced before radiographs are taken. Postreduction radiographs should be obtained to rule out an associated avulsion or osteochondral fracture of the patella.

FIGURE 37.1 Anatomy of the knee—anterior view (patella removed).

FIGURE 37.2 Anatomy of the knee—sagittal section.

FIGURE 37.3 Testing for anterior cruciate ligament injury with the Lachman test. Flex the knee 20 to 30 degrees, support the thigh with one hand, and grasp the calf with the other hand. Move the tibia forward on the femur. Observe the tibial tubercle for movement and feel for excessive forward movement of the tibia in relation to the femur.

If the history is consistent with dislocation but the patient is no longer in pain and has a normal examination, the patella may have subluxated or dislocated and self-reduced. A high-riding or laterally displaced patella may be observed. The patellar apprehension test can be performed by gently attempting to move the patella laterally. If the patient tightens the quadriceps, becomes apprehensive, or grabs the examiner’s hand, this suggests a previously subluxated (or fully dislocated) patella. Radiographs should be obtained to look for an associated osteochondral fracture.

Soft-tissue Injuries

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree