ANATOMY

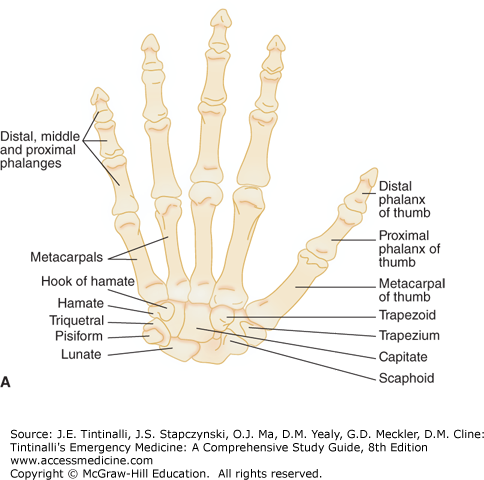

The hand consists of 27 bones: 14 phalangeal bones, 5 metacarpal bones, and 8 carpal bones arranged in five rays of metacarpals and phalanges having its base at the carpometacarpal (CMC) articulation (Figure 268-1).

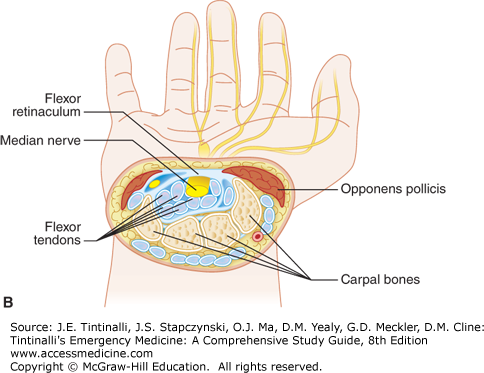

The carpal bones are made up of two rows, each with four bones. The bones are concave volarly and are bridged by the flexor retinaculum. This forms the carpal tunnel through which the median nerve and the nine long flexor tendons of the fingers pass (flexor pollicis longus [FPL]; flexor digitorum profundus [FDP] from the index, middle, ring, and small fingers; and flexor digitorum superficialis [FDS] from the index, middle, ring and small fingers) (Figure 268-2).

The index and middle finger CMC articulations have relatively little mobility, whereas the thumb, ring, and small finger CMC articulations have greater mobility at the CMC joint, which allows grasping and adaptive movements of the hand. More metacarpal deformity can be accepted in the great mobility CMC joints.

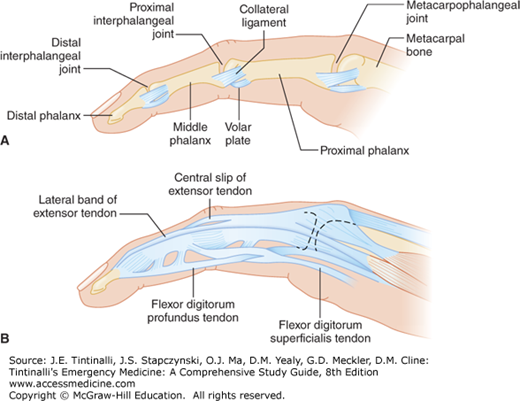

Multiple soft tissue structures support the bones and joints of the hand: capsules and ligaments provide stability, whereas muscles/tendons of the hand and forearm generate mobility (Figures 268-2, 268-3, and 268-4). The collateral ligaments of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are tightest in flexion in the index through small fingers (to allow stability in grasp), while the collateral ligaments of the MCP thumb are tight in flexion and extension (which also provide stability for the thumb in all positions) (Figure 268-3). The collateral ligaments of the interphalangeal (IP) joints are also tight throughout the entire range of motion.

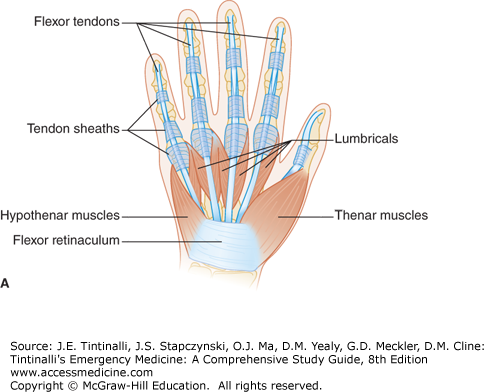

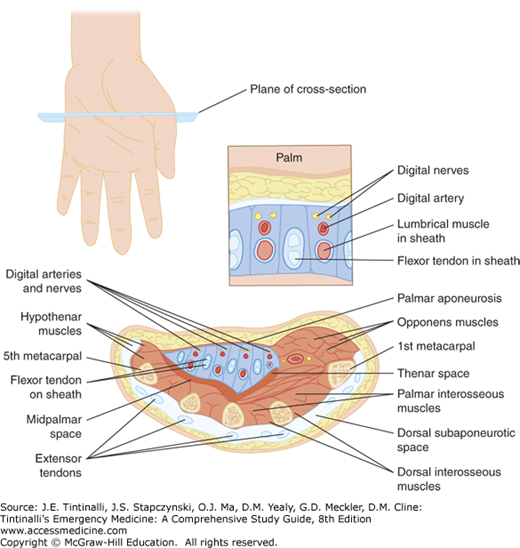

The intrinsic muscles of the hand are those that have both their origins and insertions within the hand. They consist of the thenar and hypothenar muscles, the adductor pollicis, the interossei, and the lumbricals (Figures 268-3, 268-4, and 268-5).

The thenar muscles (from superficial to deep: abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and flexor pollicis brevis) originate in the flexor retinaculum and carpal bones and insert on the radial base of the thumb proximal phalanx and the radial aspect of the first metacarpal. The motor branch of the median nerve innervates all three muscles except for the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis, which is innervated by the ulnar nerve. The adductor pollicis is innervated by the ulnar nerve and originates from the capitate and second and third metacarpals and inserts on the ulnar base of the thumb proximal phalanx.

The hypothenar muscles include, from superficial to deep, the abductor digiti minimi, the flexor digiti minimi, and the opponens digiti minimi. These muscles, innervated by the ulnar nerve, originate in the flexor retinaculum and carpal bones and insert at the ulnar base of the small finger proximal phalanx and the ulnar aspect of the fifth metacarpal.

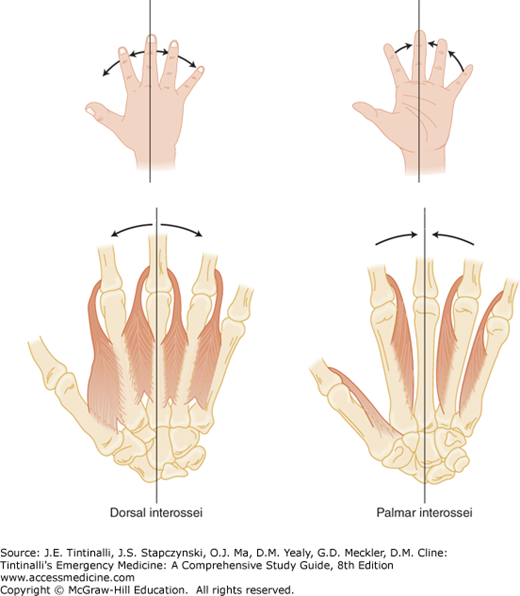

There are seven interosseous muscles, all innervated by the ulnar nerve (Figure 268-5). The three palmar and four dorsal interossei lie between the metacarpal bones and originate from them. The palmar interosseous muscle and the palmar portion of the dorsal interosseous muscle have an insertion into the extensor hood. The palmar interosseous muscle adducts the index, ring, and small finger to the midline, which is designated as the middle finger. The dorsal portion of the dorsal interosseous muscle has a tendinous insertion into the base of the proximal phalanx. The dorsal interosseous muscles abduct the fingers away from the midline.

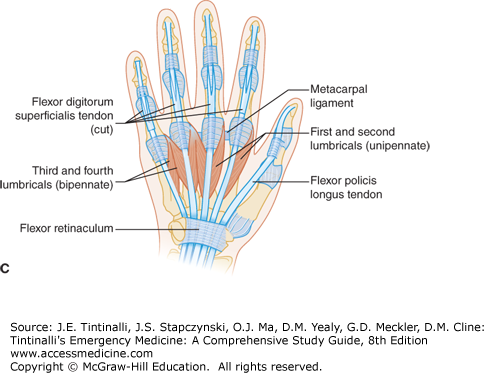

The lumbrical muscles (Figure 268-3) do not attach to bone. They arise from the FDP tendons in the palm, course radially near the MCP joints, and attach to tendons or expansions, reinforcing the interosseous lateral band on the radial side of the digit. They flex the MCP joints while extending the IP joints.The median nerve innervates the radial two lumbricals, and the ulnar nerve innervates the ulnar two. The lumbricals flex the MCP joint and extend the IP joints of the index to the small fingers. Lumbrical muscles also play a critical role coordinating the flexor and extensor systems of the digits.

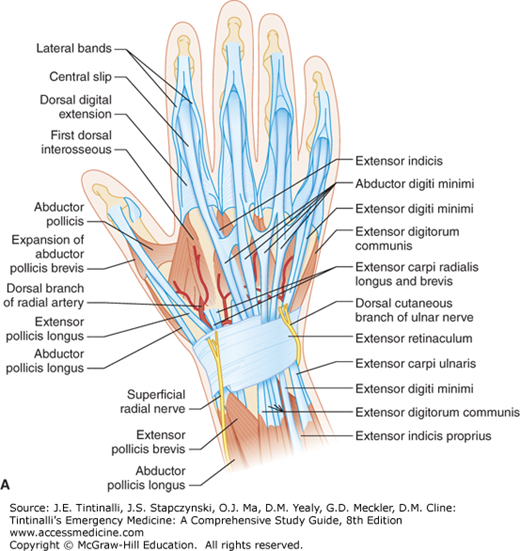

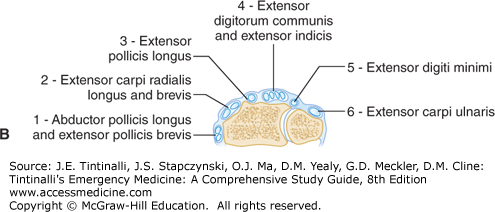

The extensor tendons course over the dorsal side of the forearm, wrist, and hand (Figure 268-4). Nine extensor tendons pass under the extensor retinaculum and separate into six compartments. In the dorsum of the hand, the extensors digitorum communis are connected by juncturae (Figure 268-6). Based on this anatomy, finger extension may still be possible with a complete tendon laceration that is proximal to the juncture. In the finger, the extensor mechanism divides into a central slip that attaches to the middle phalanx and into two lateral bands that join with the tendons of the lumbrical and interosseous muscles, which then attach to the dorsal base of the distal phalanx as the terminal tendon.

FIGURE 268-6.

Dorsal view of the hand showing juncturae tendinum. EPL, extensor pollicis longus; EPB, extensor pollicis brevis; ECRL, extensor carpi radialis longus; APL, abductor pollicis longus; ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis; EIP, extensor indicis proprius; EDC, extensor digitorum communis; EDQ, extensor digitorum quinti; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris.

The flexor tendons (flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, and palmaris longus) course over the volar side of the forearm, wrist, and hand, and primarily flex the wrist. The remaining nine tendons (four FDP, four FDS, and the FPL) pass through the carpal tunnel (Figure 268-1). The FPL goes to the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. The other four digits have two tendons each (Figure 268-2). The FDS inserts into the volar, proximal half of the middle phalanx and flexes all the joints it crosses, including the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and MCP joints. The FDP runs deep to the FDS until the level of the MCP joint, at which point it bifurcates. The FDP inserts at the volar base of the distal phalanx and acts primarily to flex the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint as well as all the PIP and MCP joints. Unlike the extensor tendons, the flexor tendons are enclosed in synovial sheaths, making them prone to deep space infections.

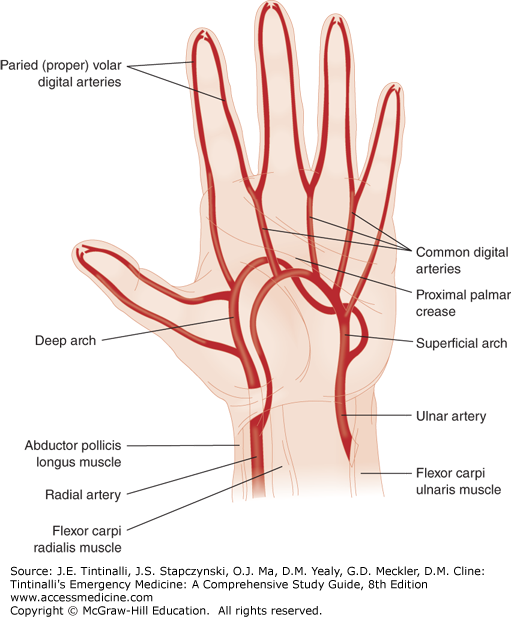

The hand and digits are perfused by the radial and ulnar arteries. The radial artery forms the deep palmar arch, whereas the ulnar artery forms the superficial palmar arch. The common digital arteries (in the second, third, and fourth web spaces) arise from the superficial palmar arch (Figure 268-7) and provide blood supply to the fingers. The blood supply to the thumb arises from the princeps pollicis, which is the radial artery as it turns into the palm. The radialis indicis, which is on the radial side of the index finger, arises from the radial artery or the princeps pollicis.

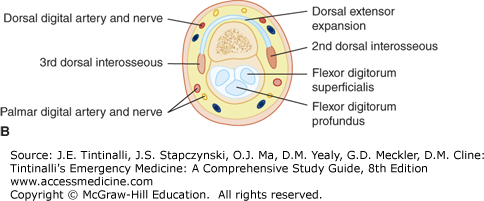

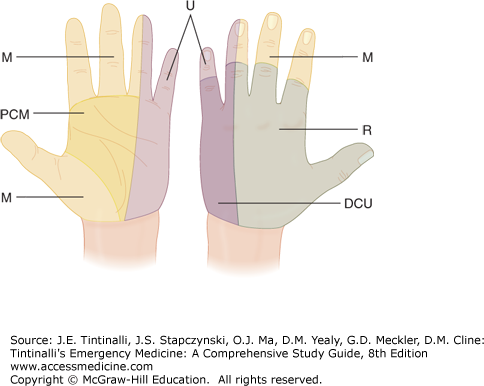

The radial, ulnar, and median nerves innervate the hand (Figure 268-8). In the hand, the median and ulnar nerves have mixed motor and sensory function. The superficial radial nerve (C5-T1) provides sensation to the dorsal radial aspect of the hand. The ulnar nerve (C7-T1) supplies sensory function to the small finger and the ulnar volar half of the ring finger and motor function to the hypothenar muscles, ulnar two lumbricals, interossei, adductor pollicis, and deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis. The median nerve (C5-T1) supplies sensory function to the thumb, index, middle, and radial volar half of the ring fingers, and motor function to the abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis brevis, and superficial head of flexor pollicis brevis. As the digital nerves course across the palm, they are superficial structures and thus are easily injured. Digital nerve sensation and two-point discrimination should be routinely assessed when evaluating lacerations of the palm (Figure 268-8). Normal two-point discrimination is 5 mm. Consult a hand specialist if the extent of injury is uncertain. In the digits, the digital nerves divide into volar and dorsal branches to supply sensation to the fingers. Knowing the location of these nerves is important to properly perform a digital block (Figure 268-3, cross-sectional view).

CLINICAL FEATURES

Do not allow a visually striking hand injury to delay the identification and treatment of other potentially life-threatening injuries. After hemorrhage control, assessment involves a detailed history, general hand examination, testing of nerves and tendons, anesthesia, and direct wound inspection. Compare with the uninjured hand, especially to identify partial motor or sensory deficits.

The history should include the time and cause of injury as well as the position of the hand at the time of injury. Ask about the possibility of associated crush, burn, injection, or chemical exposure. When applicable, determine the type and amount of chemical to which the patient was exposed. Document the patient’s occupation, avocations, prior hand injuries, and hand dominance to determine the functional impact of the injury.

Detail the extent of injury by documenting the vascularity, status of the skin, posture of the fingers, and presence of deformity or active bleeding. Ask the patient to demonstrate the hand position at the time of injury. Injuries with the digits in flexion may result in retraction of the cut end of the tendon when the digit is examined in extension. Check bilateral grip strength. Compare motor, sensory, and tendon function of both hands to assess baseline function. Test range of motion and strength against resistance. Have the patient make a clenched fist to observe the orientation and rotation of the middle and distal phalanxes. All phalanges should be oriented parallel to each other with the nails positioned in the same plane and be pointing toward the scaphoid when the fist is clenched. Circulation is assessed by regional pulses and capillary refill.1 Doppler assessment can also help assess digital artery flow.

To test the median nerve, have the patient flex the IP joint of the thumb against resistance, which tests FPL function. Alternatively, hold the index or middle finger PIP and MCP joints in extension and have the patient flex the DIP joint, which tests FDP function of the index and middle fingers. The “OK” sign will reveal the ability to flex the IP joint of the thumb and the DIP joint of the index finger. To test the motor branch of the median nerve, position the thumb in palmar abduction with the palm up. Have the patient resist a force directing the thumb toward the palm, and assess the motor power while palpating the belly of the abductor pollicis brevis muscle to ensure it is contracting. It is important to note that a laceration at the level of the wrist or distal forearm may have intact FDP function of the index and middle fingers and FPL function to the thumb because these muscles have been innervated at the proximal forearm. A median nerve injury at the level of the wrist or distal forearm can only be determined by examining two-point discrimination in the three and a half radial digits or motor branch integrity to the thenar muscles.

To assess ulnar nerve integrity, have the patient spread the fingers apart (finger abduction) and assessing the motor power by resisting a force pushing the index and small fingers to midline. Alternatively, have the patient cross the fingers. To test thumb adduction (the ulnar nerve innervates the adductor pollicis muscles), have the patient hold a piece of paper with the volar pulp of the thumb against the radial side of the PIP joint of the index finger. If the patient can maintain the key pinch of the paper against resistance then the adductor pollicis is relatively strong. If the patient cannot hold the paper and uses the FPL and flexes the IP joint to compensate for the weak adductor pollicis this is a positive Froment’s sign and indicates ulnar nerve pathology. All these reviewed maneuvers for the ulnar nerve test intrinsic muscles so that an ulnar nerve injury at the level of the wrist would be revealed by these test maneuvers.

To test the radial nerve, have the patient hyperextend the finger MCP joints against resistance, which will test the extensor digitorum communis tendons. One way to test this is to have the patient put the palm on a table, with fingers flat and hyperextended, and then lift each digit straight up and extend up from the Table while keeping the palm flat. Finger resistance can also be checked in this extended, upright position. During this maneuver, it is important to keep the finger MCP joints in hyperextension because the interossei extend the IP joints of the fingers (but flex the MCP joints), and failure to keep the digit in full extension can mislead the examiner into believing the radial nerve is intact. The interossei cannot hyperextend the finger MCP joints. By extending the thumb against resistance, the extensor pollicis longus integrity is confirmed. If a patient has a posterior interosseous nerve (which innervates the majority of the extensor muscles) palsy, the patient will be unable to hyperextend his or her fingers, but may be able to extend the wrist in a radial direction because the extensor radialis longus and extensor radialis brevis are innervated by the radial nerve proper before the posterior interosseous nerve branches.

Sensation is determined by two-point discrimination. Normal two-point discrimination is 5 mm at the volar fingertips. Older patients may have 6 mm of two-point discrimination. Compare both injured and contralateral fingers to establish a reasonable baseline, because patients may have preexisting compressive neuropathies such as carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome or previous nerve injuries. Examine the radial and ulnar sides of each finger to determine which digital nerve is injured. Hand specialists recommend repeating two-point discrimination testing two to four times on each side of the digit, because patients can guess sensation correctly by chance. At least 80% accuracy is considered acceptable. Less than 80% or indeterminate accuracy suggests the possibility of digital nerve injury. A sensory deficit also implies a potential digital artery laceration because of the close proximity of the two.

Assess full range of motion of each tendon against resistance and compare with the uninjured side. It is important to test resistance because up to 90% of a tendon can be lacerated with preservation of range of motion without resistance. In addition, the juncturae tendinum contributes to digital extension, so patients with lacerations to the extensor digitorum communis may be able to extend the digit but may not have the same motor power. Pain along the course of the tendon during resistance testing suggests a partial laceration even if strength appears adequate

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree