Chapter 2 Initiatives to Improve Patient Safety

The United States faces a paradoxical health care situation. On the one hand, the level of care available, at least at certain facilities, is among the best in the world, and many major medical breakthroughs and innovations occur in the United States. On the other hand, the U.S. health care system is dysfunctional to the point that justifiable concerns are being raised about patient safety. Approximately 15 million incidents of medical harm occur each year, averaging 40,000 such events a day (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2009b). In a large study (n = 44,000) of operations performed between 1977 and 1990, it was found that 5.4% of all surgical patients suffered complications, nearly half of which were attributable to error (Kohn et al, 2000). It has been found that 40% to 60% of surgical site infections are preventable and that antibiotics are overused, underused, misused, or used at the wrong time in 25% to 50% of all operations. The result is that as many as 13,027 perioperative deaths and 271,055 surgical complications could have been prevented (Kanter, 2007). A 2007 study found that hospital-acquired infections were associated with 99,000 deaths (Klevens, 2007). A well-known 1999 report stated that medical errors cost the U.S. health care system between $17 billion and $29 billion (Kohn et al, 2000). The full extent of the problem is so vast that it has not yet been rigorously quantified.

CURRENT HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS

Congress has called for fundamental reforms of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), moving it to a more proactive role from its previous role as “passive payer” that provides incentives for health care consumption with no links back to quality or appropriateness. The original Medicare program was designed to pay for care, as ordered, and to treat as inconsequential the quality of care. Medicare had no incentives (or even passive penalties) for such commonsense tactics as preventive medicine, withholding excessive care, or thorough patient education (Valuck, 2009). Under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, Section 5001(b), CMS was authorized to develop a pay-for-performance or value-based purchasing (VBP) program for hospitals that would tie reimbursement to achievement of certain benchmarks or goals in quality and efficiency. VBP is considered a major paradigm shift in U.S. health care. Although financial reform is no doubt needed, it is perhaps even more important to consider the role VBP could play in improving patient safety.

GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

The American Hospital Association (AHA) supports VBP but advocates moving forward carefully and with deliberation to avoid the creation of convoluted or counterproductive incentive-based payment plans. The AHA has set forth guidelines to create a workable incentive program that includes focusing on improving quality (rather than cutting costs), incremental implementation, and using measures that are evidence based, tested, feasible, and statistically sound and that recognize differences in patient populations (AHA, 2009b). VBP initiatives are some of the most fundamental changes in American health care in recent times, but other initiatives already have been used successfully to help address the safety issues in U.S. hospitals.

In 1996 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies in the United States launched a phased, multiyear initiative aimed at the large but important goal of improving the quality of health care in the United States. The first phase (1996-1999) reviewed medical literature to capture the scope of the problem, which can be summed up as the overuse, underuse, and misuse of available health care resources. In the second phase (1999-2001), the Committee on Quality of Health Care in America formulated metrics and a road map to help “cross the quality chasm” from what medical consensus determines to be sound health care practice versus what U.S. patients actually receive. Now in its third phase, this initiative seeks to put its vision into practice by creating a “more patient-responsive health system” (IOM, 2009).

Initiatives to improve patient safety may seem fairly straightforward on the surface, but crafting them can be complicated. Such measures, both public and private, have been successful in accomplishing the goals they set for themselves and finding resonance with the clinical community. The result has been a wave of initiatives that has created its own confusion. In 2006 the AHA launched the AHA Quality Center to help hospital leaders keep abreast of the many new and effective measures to improve quality and patient safety (AHA, 2009a).

An effective initiative must involve two distinct entities—health care services and health care systems—and help restructure their interaction (Clancy, 2007). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services formulated Ten Patient Safety Tips for Hospitals. The tips may be grouped into setting up quality programs at the hospital (continuous improvement, reporting systems, proper decision-making tools), creating an efficient working environment for clinicians (teamwork, limiting shifts, using appropriate-level staff, minimizing interruptions), and fundamental medical safety tips (such as infection prevention and proper use of chest tubes and urinary catheters) (AHRQ, 2009).

Part of AHRQ’s role is to provide data necessary to formulate initiatives and assess quality levels. One such successful effort is the creation of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), a program that develops patient surveys to evaluate the patient’s perception of his or her care. Data pose a unique problem in patient safety initiatives. As the U.S. health care market increasingly asks consumers to make important decisions about their own health care, the need for comprehensible patient safety data becomes urgent. Hospitals now follow no uniform national standards regarding what data they collect, how they collect data, and how these data are transmitted. Apples-to-apples comparisons can be impossible across systems. Variations in which data are collected and how they are collected can occur even among hospitals in the same system. For this reason the National Voluntary Hospital Reporting Initiative, a public-private collaborative, launched a three-state pilot program in 2003 to standardize hospital data across all systems. The goal is to collect similar data in similar ways so that meaningful comparisons can be made across the continuum of care and among facilities (American Health Quality Association, 2003).

Even today, the degree to which health care in the United States is consistent with basic quality standards is largely unknown, in part because quality studies tend to be highly focused and not indicative of overall care received by the average consumer (McGlynn and Brook, 2001). Thus it may be possible to obtain safety statistics for a specific procedure done in a specific time period at certain hospitals, but not broad safety statistics. This paucity of information contributes to the persistent belief in the United States that quality is not a serious national health care issue. In a comprehensive study, phone interviews with a random sampling of adults (n = 6712) in 12 U.S. metropolitan areas evaluated performance on 439 indicators of quality of care for 30 acute and chronic conditions and for preventive care. Aggregate scores found that only about half (54.9%) of patients received recommended care (McGlynn et al, 2003). What remains unknown is the real price tag for those patients who did not receive recommended care—in financial terms and in human suffering and even loss of life.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement Initiatives

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) (2009b) launched a groundbreaking initiative in 2004 with its aptly named 100,000 Lives Campaign, aimed at reducing deaths attributable to preventable medical errors. More than 3000 hospitals came together for an initial program credited with saving 122,000 lives in its first 18 months. Encouraged by national and grassroots-level resonance, IHI launched its 5 Million Lives Campaign in 2006, aimed at preventing 5 million cases of medical harm over a 2-year period (IHI, 2009b). More than 3800 facilities enrolled in 5 Million Lives, including more than 1500 rural hospitals (which have a special rural affinity group to address their unique needs). Building on the first six proven interventions of the 100,000 Lives Campaign, the 5 Million Lives Campaign added six more (Box 2-1).

BOX 2-1 IHI Proven Interventions

THE SIX INTERVENTIONS FROM THE 100,000 LIVES CAMPAIGN

• Deploy Rapid Response Teams… at the first sign of patient decline

• Deliver Reliable, Evidence-Based Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction… to prevent deaths from heart attack

• Prevent Adverse Drug Events (ADEs)… by implementing medication reconciliation

• Prevent Central Line Infections… by implementing a series of interdependent, scientifically grounded steps

• Prevent Surgical Site Infections… by reliably delivering the correct perioperative antibiotics at the proper time

• Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia… by implementing a series of interdependent, scientifically grounded steps

NEW INTERVENTIONS TARGETED AT HARM

• Prevent Harm From High-Alert Medications… starting with a focus on anticoagulants, sedatives, narcotics, and insulin

• Reduce Surgical Complications… by reliably implementing all of the changes recommended by SCIP, the Surgical Care Improvement Project (www.medqic.org/scip)

• Prevent Pressure Ulcers… by reliably using science-based guidelines for their prevention

• Reduce Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection… by reliably implementing scientifically proven infection control practices

• Deliver Reliable, Evidence-Based Care for Congestive Heart Failure… to avoid readmissions

• Get Boards on Board… by defining and spreading the best known leveraged processes for hospital boards of directors, so that they can become far more effective in accelerating organizational progress toward safe care

From Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Protecting 5 million lives from harm, available at http://www.ihi.org/NR/rdonlyres/EB78B6DB-0955-4C9C-A9B8-599E1E53DF6D/0/5MillionLivesCampaignBrochure0207.pdf. Accessed on August 18, 2009.

The eighth intervention of the 5 Million Lives campaign refers to the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP), a well-known program for surgical safety. SCIP’s genesis was in 2002, when CMS and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Findings from this project on preventable surgical site infections and inappropriate use of antibiotics resulted in the creation of SCIP, a suite of national initiatives to improve the care of Medicare patients receiving surgery. The original goal of SCIP was to reduce preventable surgical morbidity and mortality by 25% by 2010. Using outcome, process, and test measures, SCIP periodically identifies, measurable outcomes of preventable complications specific to the surgical setting (Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 Surgical Care Improvement Project National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures

| Set Measure ID # | Measure Short Name |

|---|---|

| INFECTION | |

| SCIP Inf-1 | Prophylactic antibiotic received within one hour prior to surgical incision. |

| SCIP Inf-2 | Appropriate antibiotic received. |

| SCIP Inf-3 | Prophylactic antibiotic discontinued within 24 hours after surgery end (48 hours for cardiac surgery). |

| SCIP Inf-4 | Cardiac surgery patients with controlled 6 am postoperative blood glucose. |

| SCIP inf-6 | Appropriate hair removal for surgery patients. |

| SCIP Inf-9 | Urinary catheter removed on postoperative (POD) Day 1 or POD Day 2 |

| SCIP Inf-10 | Surgery patients with perioperative temperature management. |

| VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM | |

| SCIP VTE-1 | Recommended VTE prophylaxis ordered. |

| SCIP VTE-2 | Appropriate VTE prophylaxis received within 24 hours prior to surgery to 24 hours after surgery. |

| CARDIAC | |

| SCIP Card-2 | Surgery patients on beta-blocker therapy prior to arrival who receive a beta-blocker during perioperative period. |

The Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures (Version 3.0c, November 06, 2009) is the collaborative work of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission. The Specifications Manual is periodically updated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission.

Modified from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), The Joint Commission (TJC): Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures (specifications manual), version 3.0c, 2009, available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2Fpage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1228695698425. Accessed December 14, 2009.

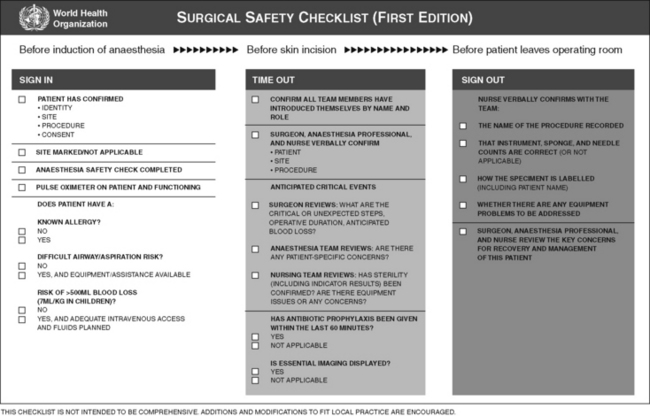

At the beginning of 2009 IHI launched a new campaign called the IHI Improvement Map, which retains the 12 patient safety interventions from the 5 Million Lives campaign and adds 3 more: (1) the World Health Organization (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist, (2) prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and (3) ability to link quality and financial management—engage the chief financial officer and provide value for patients (IHI, 2009a). The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist (Figure 2-1) gained recognition following a study describing how its use significantly reduced patient morbidity and complications (Haynes et al, 2009). In hospitals where the checklist was used, postoperative complication rates fell by 36% on average, and death rates fell by a similar amount (Haynes et al, 2009).

Figure 2-1 WHO Surgical Safety Checklist.

(From World Health Organization: Surgical safety checklist, available at http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/ss_checklist/en/index.html.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree