INTRODUCTION

Most ED chief complaints involving skin lesions are due to infections, irritants, and allergies.1 Visual pattern recognition is the key to diagnosis. The recommended approach for the diagnosis of a skin disorder in the ED (assuming resuscitation or stabilization is not required) is to:

Determine the chief complaint.

Obtain a brief history (duration, rate of progression, and location of lesions).

Perform the dermatologic examination (morphology and extent of distribution).

Formulate the age-appropriate differential diagnosis based on lesion morphology and distribution.

Elicit additional concerns from the history (associated complaints, comorbidity, medications, or exposures), and include or exclude syndromes in the differential diagnosis based on this information.

Evaluate for systemic involvement, and consider ancillary investigations, if necessary.

Obtain dermatologic consultation, if necessary, and arrange for appropriate referral (primary care or dermatologic).

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Determine the chief complaint and obtain a brief history (discomfort, duration, rate of progression, percentage of body surface involvement, and location of lesions). The secondary history should include issues relating to the lesion: morphology, evolutionary nature, rate of progression, and distribution. Associated systemic complaints and mucosal systems must be identified. Ask about exposures, immunizations, toxins, chemicals, foods, animals, insects, plants, and ill contacts. Sexual history, if appropriate, and medical and family histories should be reviewed. If applicable, a detailed occupational history should be obtained; industrial exposure may be the causative etiology. Asking about medication use, sun exposure, travel history, or particular food ingestion also may yield helpful information. Be sure to include any other housemates or partners in your history of exposures; contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to fragrances or other products that a partner is using.2 The patient should also be asked about the degree of discomfort of the dermatoses; a painful dermatitis is often a red flag and is not usually associated with a self-limiting lesion.3

A detailed medication history is important and particular attention should be paid to recently started drugs or dosage increases. Erythema multiforme, exfoliative dermatitis, photosensitivity reactions, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and vasculitis are common medication-induced drug reactions. Dermal necrosis should prompt consideration of anticoagulant use, whereas a diffuse rash in a patient on sulfa drugs, anticonvulsants, or some antimicrobials may aid the clinician in diagnosing Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

The patient should be gowned and in a room with adequate lighting and appropriate privacy to allow entire skin examination. Inspect all skin and mucosal surfaces, including hair, nails, scalp, and mucous membranes. Then evaluate the specific skin lesions. A magnifying lens and a portable light are helpful aids.

Examine the skin systematically. Determine the distribution, pattern, arrangement, morphology, extent, and evolutionary changes of the lesions. Distribution is the location of the skin findings, and the pattern is their anatomic, functional, and physiologic arrangement. For example, a unilateral band-like arrangement of lesions on the thorax suggests varicella-zoster virus infection. Skin diseases often present with a predilection for certain body areas; the distribution of lesions will assist in narrowing the diagnostic possibilities. From the anatomic perspective, the skin surfaces that are usually considered as separate areas of distribution are generalized body; face and scalp; trunk and axillae; groin and skin folds; and hands, feet, and nails. The extremities may be further subdivided into upper versus lower, proximal versus distal, wrists versus ankles, and hands versus feet.

In a patient with diffuse erythema in whom toxic shock syndrome is suspected, the presence of a foreign body such as a retained tampon should be investigated. Petechia should prompt the investigation of meningococcemia or Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Rashes on exposed portions of the skin should prompt inquiries about sun exposure, jewelry, topical agents, or exposures. See Table 248-1 for a differential diagnosis of skin lesions as a function of location, including both distribution and pattern considerations.

| Distribution and Pattern | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Flexor surfaces | Atopic dermatitis, candidiasis, eczema, ichthyosis |

| Sun exposure (face, upper thorax, distal extremities) | Sunburn, photosensitive drug eruption, photosensitive dermatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, viral exanthem, porphyria |

| Distal extremities | Viral exanthem, atopic or contact dermatitis, eczema, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, gonococcemia |

| Front and back of chest | Pityriasis rosea, secondary syphilis, drug eruption, atopic or contact dermatitis, psoriasis |

| Clothing covered (thorax and distal lower extremities) | Contact dermatitis, psoriasis, folliculitis |

| Acneiform (face and upper thorax) | Acne, drug-induced acne, irritant dermatitides |

Use the burn rule of nines (see chapter 216, “Thermal Burns”) to estimate the degree of skin involvement in disorders with widespread distribution. This calculation also may be used to determine the amount of topical medication required for a specific treatment course or whether an oral medication might be more appropriate. Extensive erythroderma (often >90% of body surface area) is a dermatologic emergency.3,4 Severe erythroderma can represent underlying severe infectious dermatitis, toxic shock syndrome, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, drug reaction, psoriasis, or seborrheic dermatitis.

Lesion arrangement refers to the symmetry and configuration. Bilateral symmetry suggests a systemic internal event or symmetric external exposure, as seen in erythema multiforme, with plaque-like lesions on the flexor surfaces of the extremities, or contact dermatitis related to a lotion application. An asymmetric arrangement supports a localized process. Configuration may apply to a single lesion with reference to its individual features or, alternatively, to multiple lesions and their relation to one another. For instance, internal configuration is illustrated by the relation between the central papule relative to the erythematous ring in the target lesion of erythema multiforme; on the total-body scale, configuration is demonstrated by clustering of lesions in a herpesvirus infection or by a linear arrangement as with a reaction from poison ivy or oak. Other terms used to describe the lesion configuration are listed in Table 248-2.

| Descriptor | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Annular | Ring-like or pertaining to the outer edge |

| Arcuate | Curved or pertaining to the curve |

| Circinate | Circular |

| Confluent | Blending together |

| Dermatomal | Belt-like or limited to one side of the body in anatomic dermatome |

| Discoid | Solid, round, slightly raised, or pertaining to a disk |

| Discrete | Separate or individual |

| Grouped | Clustered |

| Guttate | Scattered |

| Gyrate | Coiled or winding |

| Herpetiform | Creeping |

| Iris | Concentric circles |

| Linear | In a line |

| Polycyclic | Overlapping circles or borders of irregular curves |

| Retiform | Net-like |

| Serpiginous | Snake-like |

Recognition of the primary lesion is vital in establishing the diagnosis; the use of the primary lesion’s morphology is very important regarding the generation of an appropriate differential diagnosis and ultimately the correct dermatologic diagnosis. The primary lesion is the one that has not been altered by secondary issues, including healing, complicating infection, medication application, or scratching. Examples of primary skin lesions are macules, papules, nodules, tumors, cysts, plaques, wheals, vesicles, bullae, and pustules. Careful attention should be paid to a nonblanching lesion. Secondary lesions have had their appearance altered due to disease evolution or various external factors, as noted earlier, and include crusts, scales, fissures, erosions, ulcerations, excoriations, atrophy, scarring, and lichenification. See Table 248-3 for a listing and descriptions of the various morphologic descriptors of dermatologic lesions; see Tables 284-4 and 284-5 for a differential diagnosis of the various skin disorders relative to primary and secondary lesion morphologies.

| Descriptor | Morphology | Lesion Nature | Height Relative to Adjacent Skin | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excoriation | Linear marks from scratching | Secondary | Flat |  |

| Erosion | Ruptured vesicle or bulla with denuded epidermis | Secondary | Depressed |  |

| Fissure | Linear cracks on skin surface | Secondary | Flat |  |

| Ulcer | Epidermal or dermal tissue loss | Secondary | Depressed |  |

| Macule | Flat, circumscribed discoloration ≤1 cm in diameter; color varies | Primary | Flat |  |

| Petechiae | Nonblanching purple spots <2 mm in diameter | Primary | Flat |  |

| Sclerosis | Firm, indurated skin | Secondary | Flat or elevated |  |

| Telangiectasia | Small, blanchable superficial capillaries | Primary | Flat |  |

| Purpura | Nonblanching purple discoloration of the skin | Primary | Flat |  |

| Abscess | Tender, erythematous, fluctuant nodule | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Cyst | Sack containing liquid or semisolid material | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Nodule | Palpable solid lesion <1 cm in diameter | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Tumor | Palpable solid lesion >1 cm in diameter | Primary | Elevated |

|

| Scar | Sclerotic area of skin | Secondary | Flat or elevated |  |

| Wheal | Transient, edematous papule or plaque with peripheral erythema | Primary | Flat or elevated |  |

| Vesicle | Circumscribed, thin-walled, elevated blister <5 mm in diameter | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Bulla | Circumscribed, thin-walled, elevated blister >5 mm in diameter | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Pustule | Vesicle containing purulent fluid | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Papule | Elevated, solid, palpable lesion <1 cm in diameter; color varies | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Plaque | Flat-topped elevation formed by confluence of papules >0.5 cm in diameter | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Comedo | Papule with an impacted pilosebaceous unit | Primary | Elevated |  |

| Lesion Morphology | Differential Considerations | Images |

|---|---|---|

| Macule | Drug eruption (fixed or photosensitive), nevus, tattoo (ink), rheumatic fever, syphilis (secondary), viral exanthema, toxic or infectious erythemas, meningococcemia (early), external trauma (ecchymosis), vitiligo, tinea versicolor, cellulitis (early) |  |

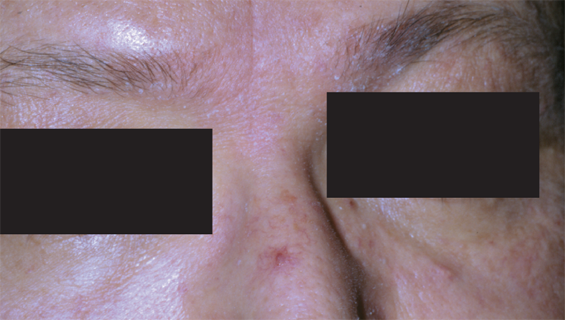

| Papule | Acne, basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, nevus, warts, molluscum contagiosum, skin tags, atopic dermatitis, urticaria, eczema, folliculitis, insect bites, vasculitis, psoriasis, scabies, Toxicodendron dermatitis (poison ivy, oak, sumac), erythema multiforme, varicella (early), gonococcemia |  |

| Plaque | Eczema, pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis and versicolor, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, urticaria, syphilis (secondary), erythema multiforme |  |

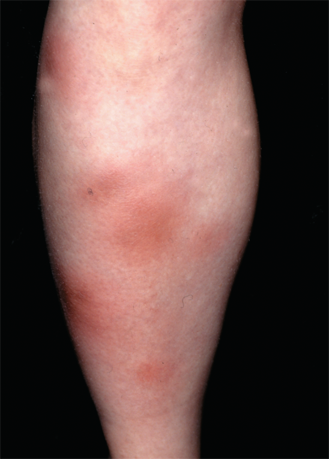

| Nodule | Basal cell, squamous cell, or metastatic carcinoma; melanoma; erythema nodosum; furuncle; lipoma; warts |  |

| Wheal | Urticaria, angioedema, insect bites, erythema multiforme |  |

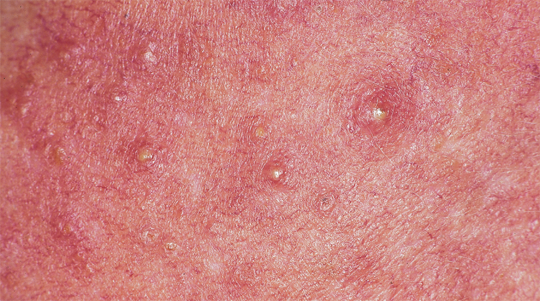

| Pustule | Acne, folliculitis, gonococcemia, hidradenitis suppurativa, herpetic infection (herpes simplex, herpes zoster, varicella), impetigo, psoriasis, rosacea, pyoderma gangrenosum |  |

| Vesicle | Herpetic infection (herpes simplex, herpes zoster, varicella), impetigo, Toxicodendron dermatitis (poison ivy, oak, sumac), thermal burn, friction blister, toxic epidermal necrolysis, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris |  |

| Bulla | Bullous impetigo, Toxicodendron dermatitis (poison ivy, oak, sumac), thermal burn, friction blister, toxic epidermal necrolysis, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris |  |

| Lesion Morphology | Differential Considerations | Images |

|---|---|---|

| Scales | Psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, toxic and infectious erythemas, syphilis (secondary), dermatophytic infection (tinea), tinea versicolor, xerosis (dry skin), thermal burn (first degree) |  |

| Crusts | Eczema, dermatophytic infection (tinea), impetigo, contact dermatitis, insect bite |  |

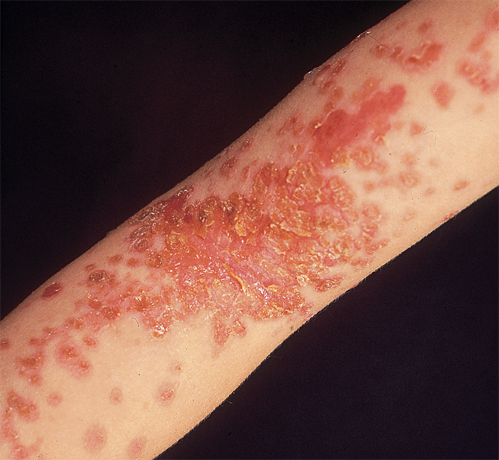

| Erosions | Candidiasis, dermatophytic infection (tinea), eczema, toxic epidermal necrolysis, toxic-infectious erythemas, erythema multiforme, primary blistering disorders (bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris), brown recluse spider envenomation |