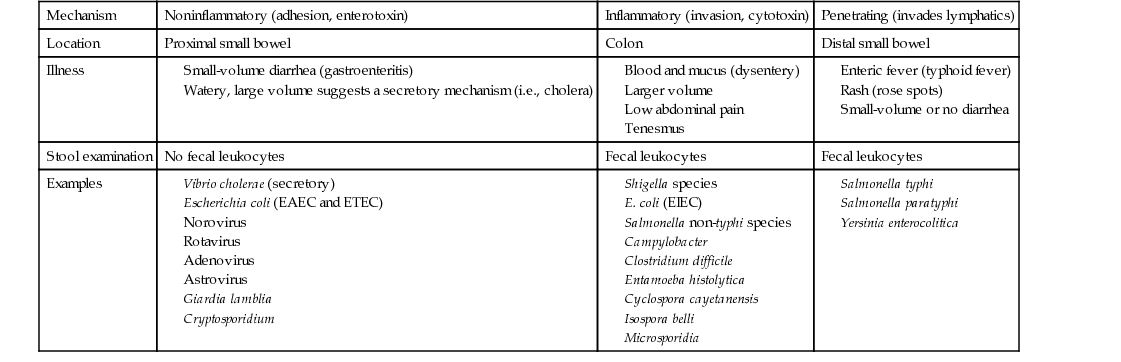

Thomas H. Taylor Diarrhea is an alteration of normal bowel movement characterized by an increase in volume or frequency of stools. If the predominant symptoms are nausea and vomiting, viral gastroenteritis (i.e., noroviruses in adults and rotavirus in children) as well as food poisoning caused by the ingestion of preformed toxin (i.e., Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus cereus) should be considered. If the predominant symptom is diarrhea, upper and lower bowel pathogens of the small intestine and colon, respectively, should be considered. Infections of the small intestine (upper intestinal diarrhea) cause less-frequent, small-volume, noninflammatory stools and are caused by enteric viruses, enterotoxic bacteria (e.g., enterotoxic Escherichia coli), and noninvasive parasites such as Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Small-volume diarrhea is the consequence of the great capacity of our colon to absorb water from the more proximally diseased small bowel. Infections of the colon (lower intestinal diarrhea) are more likely to cause frequent, large-volume, inflammatory diarrhea, which is recognized by fever and mucus and blood in the stool, often referred to as dysentery. When dysentery is present, Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), and Entamoeba histolytica are likely pathogens. Dysentery is often associated with tenesmus, or pain and cramping in the rectum and left lower quadrant, with straining, spasm of the rectal sphincter, and ineffectual evacuation. Fecal leukocytes and stool Hemoccult smears are routinely tested to help differentiate inflammatory diarrhea from noninflammatory diarrhea. Watery diarrhea is a type of noninflammatory, small bowel diarrhea suggestive of a secretory mechanism. It is likely to be abrupt in onset, very large in volume, and associated with symptoms of acute loss of blood volume (shock); cholera is implicated. In this case, the capacity of the distal colon to absorb watery diarrhea produced in the small intestine is overwhelmed. Penetrating diarrhea refers to organisms that may cause a sometimes unrecognized inflammatory process, usually in the distal small bowel, with eventual invasion into the bloodstream associated with systemic manifestations referred to as enteric fever (i.e., Salmonella typhi or typhoid fever). Table 232-1 outlines the differences among noninflammatory, inflammatory, and penetrating diarrheas. Infectious diarrheal diseases are the second leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the United States, each person experiences one or two bouts of diarrhea each year, or some 200 million to 375 million episodes of diarrheal illness occur each year, resulting in 3000 to 5000 deaths.1 Infectious diarrhea is a problem for both industrialized and developing nations, but it is uniquely associated with high morbidity and mortality in developing nations. Inadequate food and water supplies lead to recurrent bouts of diarrhea in very young children, who are not able to maintain adequate hydration during acute episodes but, more important, have baseline malnutrition. Malnutrition sets them up for gastrointestinal infection, and recurrent infection worsens malnutrition. Recurrent bouts of diarrhea weaken bowel health in a fashion that leads to chronic diarrhea. The situation is worsened by the fact that infectious diseases such as measles remain rampant in developing nations and are often not survivable in malnourished children. Rotavirus, a common cause of childhood viral gastroenteritis even in the United States, shares this proclivity to cause death in malnourished children. Fortunately, modes of transmission are well known and include three main routes: food-borne, water-borne, and person to person (fecal-oral). Non-typhi Salmonella species and Campylobacter jejuni are transmitted through food, but norovirus has become the most common food-borne diarrhea.2 Shigella species are transmitted mainly person to person. Giardia and Cryptosporidium are principally water-borne. International health initiatives have made progress in reducing the global annual childhood mortality rate from 5 million to 1.5 million deaths per year by promotion of breastfeeding, measles and rotavirus vaccination programs, education about oral rehydration therapy (ORT), food distribution programs, and separation of drinking water from bathing and bathroom facilities. Residents of industrialized nations experience one or two bouts of diarrhea annually, compared with five or six in underdeveloped areas, but certain individuals may be affected more frequently and severely (Box 232-1). Viruses, bacteria, and parasites can all cause diarrhea. Viral infections usually occur on a year-round basis but peak in the winter months. Bacterial illnesses are more common in the summer or early fall. Acute infectious diarrhea may be categorized as noninflammatory, inflammatory, or penetrating and thus cause unique clinical scenarios. E. coli organisms have the potential to exchange plasmids and other transgenic virulence factors, which run the gamut of pathogenic mechanisms. Because E. coli is part of normal bowel flora, special techniques must be requested to discover pathogenic species. Distinct syndromes follow these four pathogenic mechanisms: A good medical history is most helpful in determining the cause of infectious diarrhea and directing the extent of diagnostic testing. The epidemiologic setting, clinical presentation, and laboratory features guide our empirical approach to a broad spectrum of pathogens. Given that most acute diarrhea in the United States is caused by noroviruses (50% to 80%),2 which produce mild noninflammatory gastroenteritis with fewer than six low-volume stools per day, and that it is self-limited with resolution in 2 to 3 days, the health care provider should investigate and give antibiotics only for presentations not consistent with norovirus infection. The probability that this is not norovirus infection increases dramatically if there are epidemiologic clues: travel, antibiotic use, hospital-acquired infection, outbreak association, animal or pet contact, hiker drinking untreated water, shellfish ingestion, unpasteurized milk ingestion, uncooked eggs, and day care client or worker. The provider should consider bacterial causes (Table 232-2) if the clinical presentation is one of inflammatory diarrhea: fever, abdominal pain, tenesmus, large-volume diarrhea, more than six stools per day, and mucus or blood in stool. A search for the pathogen with empirical antibiotic treatment is in order. TABLE 232-2 Clinical Signs and Disease Probability The presence of chronic illness, chemotherapy, tube feedings, medications, immune deficiency, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with low CD4 counts will prompt consideration of more severe manifestations of norovirus, rotavirus, adenovirus, or astrovirus infection and atypical presentation of bacterial and parasitic diarrhea. Chronic diarrhea, lasting more than 14 days, is suggestive of protozoan parasites: Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and E. histolytica. Systemic manifestations of fever, chills, rigors, night sweats, and weight loss suggest penetrating bacteria (i.e., S. typhi or Yersinia enterocolitica), and blood cultures are in order. Chronic or recurrent diarrhea is also suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease, such as ulcerative colitis or regional enteritis. Irritable bowel syndrome may be present in a diarrhea-predominant form, which has been recently related to idiopathic adult-onset bile malabsorbtion.3 Some bacterial pathogens and toxins may cause noninflammatory, self-limited disease in healthy people, but if they produce only norovirus-like illness, patients would not benefit from extensive laboratory tests or antibiotic treatment. Older adults or very young patients may develop complications from gastroenteritis or mild diarrhea and may benefit from hydration and admission, even if a pathogen search and antibiotics are withheld. A temporal association should be sought with medications related to diarrhea or food related to bacterial toxins, such as mayonnaise, cream pie, and potato salad (staphylococcal enterotoxin) or rice dish on the warming table (B. cereus food poisoning); an association that would ensure a good prognosis without need for antibiotics. The physical examination includes weight, temperature, and orthostatic vital signs (blood pressure and heart rate lying, sitting, and standing) to assess volume depletion (dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, absent jugular venous pulsation). The patient’s mental status should be noted along with a close assessment of skin color, temperature, and rashes. Signs of bowel perforation include an abdomen quiet to auscultation and rigid to palpation. Small bowel obstruction might include a tender abdomen, with distention and high-pitched bowel sounds, as opposed to the usual bowel rushes and scaphoid abdomen seen with diarrheal enteritis. Thyromegaly, tachycardia, and proptosis suggest hyperthyroidism as a cause of chronic diarrhea. Lymphadenopathy, especially cervical node, suggests lymphoma or bowel cancer as a cause of diarrhea. In the female patient with lower abdominal symptoms, a pelvic examination is imperative. In the geriatric patient, fecal impaction must be ruled out. All patients should now be tested for HIV infection, and diarrhea is a good indication. For the patient who has mild acute diarrhea or gastroenteritis, diagnostic evaluation is typically not indicated. This diarrhea is usually viral and considered benign. Symptoms commonly resolve within 1 week, often within 1 to 3 days, and a diagnosis is rarely helpful. Complete blood count (CBC), serum electrolyte values, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine concentrations are standard tests for evaluation of electrolyte derangement and dehydration. A stool sample for fecal leukocytes and occult blood should be taken for patients with a temperature above 38.8° C (102° F), bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, or more than six unformed stools in a 24-hour period and for patients who are frail and elderly or immunocompromised. Stool evaluation for occult blood and fecal leukocytes helps differentiate between inflammatory and noninflammatory diarrhea. Fecal leukocytes (or immunoassay for the neutrophil protein lactoferrin) are associated with Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, C. difficile, and EHEC. If fecal leukocytes are present, typically in inflammatory diarrhea, the stool should be further evaluated by stool culture and perhaps for ova and parasites.4 Diarrhea that develops after hospitalization is unlikely to represent infection with Giardia or Cryptosporidium and should not be tested for ova and parasites. Systemic leukocytosis is suggestive of C. difficile infection, and a stool sample for C. difficile toxin B is sent. The old enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which required reflex testing for toxin, has been largely replaced by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for toxin B gene.5 This real-time test for the toxin B gene is more sensitive (98.7%) and specific (87.5%). It is not necessary to send more than one test sample for C. difficile, and the test should not be performed on formed stool. Colonoscopy may differentiate inflammatory bacterial colitis, C. difficile, invasive E. coli, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC), or cytomegalovirus from inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, and irritable bowel disease.6 There is some risk of bowel perforation, especially in the setting of pseudomembranous colitis. Computed tomography (CT) imaging is useful to discover mucosal thickening, hemorrhage, abscess, malignancy, and inflammatory colitis. Mucosal thickening and pericolonic stranding are signs of C. difficile–associated pseudomembranous colitis. A good history investigating epidemiology, clinical signs, and routine diagnostic tests allow consideration of broad categories: noninflammatory, inflammatory, and penetrating gastrointestinal illness. Noninflammatory illness suggesting gastroenteritis, norovirus, rotavirus, or traveler’s diarrhea is differentiated from more inflammatory and penetrating disease; it requires only hydration and electrolyte replacement, without stool or blood culture or further diagnostic testing. Norovirus, the most common cause of viral gastroenteritis or “intestinal flu” in older children and adults, is a member of the Caliciviridae family of small RNA viruses. Human caliciviruses cause disease year-round but are the most common cause of outbreaks of “winter vomiting syndrome”; they occur frequently in closed systems, such as cruise ships, hospitals, nursing homes, and military facilities. These viruses require low inocula, are highly transmissible, and are resistant to cooking and chlorine cleaners. Shellfish, such as clams and oysters, are filter feeders and readily concentrate organisms from contaminated water. Nonbacterial, food-related outbreaks are usually a result of these agents. The incubation period for various caliciviruses is only 1 or 2 days. Winter vomiting disease is characterized by abrupt onset of vomiting, diarrhea, and low-grade or no fever. The duration is also short, 1 to 3 days. Treatment consists of ORT, and antibiotics are not indicated.7 Travelers are asked not to take antibiotic treatment, unless symptoms fail to subside within 24 hours. Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe diarrhea in very young children. There is a seasonal pattern, from November to April in the United States. Fecal-oral transmission may occur through contaminated water, food preparation, and hands. Rotavirus invades small intestine villous enterocytes, causing malabsorption, and produces a viral enterotoxin, which induces a secretory diarrhea by stimulating chloride secretion but without cyclic nucleotide signaling (i.e., not a cholera toxin). Thus the diarrhea is watery and lasts 3 to 8 days, and it is cholera-like in its ability to dehydrate and to cause death in young malnourished children. Vomiting and fever may be prominent symptoms, as in other gastroenteritis. The incubation period is 4 to 7 days. Antibiotics are not warranted, and treatment is ORT. In the United States, 1 of 40 children will require admission for intravenous fluid resuscitation.8 Although rotavirus is also associated with disease in winter months, rotavirus disease in older children and adults is mild, short-lived, and thus underreported. Two vaccines, RotaTeq (RV5: three doses at 2, 4, and 6 months) and Rotarix (RV1: two doses at 2 and 4 months), have reduced infant mortality in developing nations and morbidity in developed nations. These live vaccines should be used with caution in immunocompromised children, but HIV positivity is not a contraindication.

Infectious Diarrhea

Definition

Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Signs

Disease

Nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain

Small volume, short course

Norovirus, rotavirus, adenovirus, astrovirus

Escherichia coli (EAEC and ETEC)

Blood or mucus in stool, low abdominal pain

Large volume

Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter

E. coli (EIEC), Clostridium difficile, Entamoeba histolytica

Watery stool, large volume, shock

Cholera, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC)

Rectal pain and tenesmus

Shigella, Entamoeba histolytica

Fever (temperature >101° F), chills, night sweats, weight loss

Salmonella typhi, Yersinia enterocolitica

Chronic diarrhea

Cryptosporidium, Giardia, E. histolytica, Campylobacter, Yersinia

HUS

E. coli O157:H7 or other STEC

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Campylobacter jejuni

Physical Examination

Diagnostics

Differential Diagnosis

Noninflammatory Diarrhea: Acute Gastroenteritis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Infectious Diarrhea

Chapter 232