CHAPTER 47

Identification and Management of Temporomandibular Disorders

Golaleh Barzani, DMD • Harry Dym, DDS

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a collective term embracing several clinical problems including disorders of masticatory, cervical musculature, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and associated structures. The key to treatment of most TMDs is proper understanding of the structural changes within the TMJ and the factors that influence muscle function. Much of the difficulty with the treatment of these patients is attributed to the clinician’s ability to accurately diagnose the problem. It is very important for nurses and physician assistants to be familiar with TMDs and their treatment because often these practitioners are the first people to identify and treat these disorders.

This chapter attempts to provide a comprehensive guide for clinicians to properly identify and provide initial appropriate treatment for these conditions. More importantly, it aims to help clinicians have a better understanding of various TMJ disorders and to help with appropriate and prompt referral to specialists when necessary.

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

Painful disorders of the TMJ involve trigeminal nerves: V1 ophthalmic, V2 maxillary, and V3 mandibular. Each branch also contains motor fibers that innervate the muscles of mastication. Pain receptors are divided into two groups based on their size, myelination, and rate of transmission. The larger A delta fibers are myelinated and, therefore, transmit pain quickly and are the most important pain fibers. The smaller, nonmyelinated fibers or C fibers are more susceptible to chronic, dull pain and pressure. Both pain fibers have input from trigeminal ganglia to the spinal nucleus with subsequent synapses, which lead to the postcentral gyrus and the reticular activating system. The fact that several other areas are innervated by the trigeminal nerves helps explain referred pain from the TMJ.

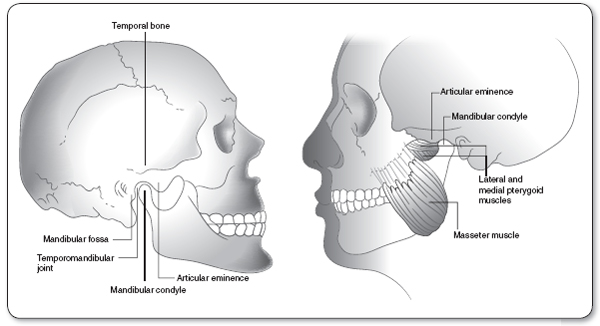

TMJ consists of the moving condyloid process of the mandible that articulates with the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone (Figure 47.1). The anterior portion of the glenoid fossa is the articular eminence. The external auditory canal is located posteriorly. The zygomatic process lies laterally and the styloid process lies medially. The surfaces of condyles and the glenoid fossa are lined with fibrous connective tissue, which is primarily a layer of hyaline cartilage. Between the condylar process and glenoid fossa is the cartilaginous disc that provides a stable platform for rotational and gliding movements of the joint. It also acts as a shock absorber. Any alteration in normal position of the disc is known as internal derangement or ID. The mandible is held medially and laterally by a set of capsular ligaments; posteriorly is the retrodiscal pad. More posteriorly and medially are the stylo- and sphenomandibular ligaments. Tendons of the muscles of mastication suspend the mandible.

In the healthy joint, the disc and condyle are considered one continuous anatomical structure. Lateral and medial ligaments and the retrodiscal pad have connections between the disc and the condyle; therefore, the essential cause of disc disorder is a pathologic change in the ligamentous attachments of the disc–condyle complex (Alomar et al., 2007).

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

It is crucial for a clinician to properly recognize and diagnose TMDs in order to render proper treatment. The following outline is the clinician’s guide to proper evaluation and diagnosis of patients with TMDs (American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons [AAOMS] Parameters of Care, 2012).

History and Physical Examination

detailed history, head and neck evaluation, and general physical examination when indicated.

Comprehensive Evaluation

The following questionnaire has been adapted to help clinicians properly evaluate and assess TMJ pain and symptoms. It is important to note that during this interview all findings should be from the patient’s perspective. These results should be followed by a clinical evaluation and report.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR QUESTIONNAIRE

Chief complaints

Chief complaints

When did you first notice this problem?

When did you first notice this problem?

Was there any event that you believe may have caused this problem?

Was there any event that you believe may have caused this problem?

Associated complaints

Associated complaints

Present illness

Present illness

Accident or traumatic injury to face, head, or jaw

Accident or traumatic injury to face, head, or jaw

Past surgical history

Past surgical history

Dental surgery with prolonged pain or dysfunction

Dental surgery with prolonged pain or dysfunction

Orthodontic treatment

Orthodontic treatment

New crowns or fillings

New crowns or fillings

Severe headaches

Severe headaches

Migraine headaches

Migraine headaches

Repeated earaches

Repeated earaches

Ringing in ears

Ringing in ears

Noise in jaw

Noise in jaw

Neck, shoulder, or back pain

Neck, shoulder, or back pain

Sinus problems

Sinus problems

Sensitive teeth

Sensitive teeth

Dizziness

Dizziness

Ulcers

Ulcers

Changes in hearing

Changes in hearing

Stuffy feeling in ears

Stuffy feeling in ears

Depression

Depression

Difficulty sleeping

Difficulty sleeping

Arthritis

Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Pain assessment:

Pain assessment:

Duration

Duration

Location

Location

Frequency

Frequency

Character

Character

– Dull

– Sharp

– Throbbing

– Burning

Pattern of pain

Pattern of pain

Constant or intermittent

Constant or intermittent

Does anything make the pain worse or better?

Does anything make the pain worse or better?

Severity 0–10 (0 no pain, 10 worst pain)

Severity 0–10 (0 no pain, 10 worst pain)

Factors that affect pain

Factors that affect pain

Chewing

Chewing

Bruxism

Bruxism

Diet

Diet

Medication

Medication

Weather

Weather

Clenching or grinding at night or during day

Clenching or grinding at night or during day

Heat

Heat

Other

Other

Dysfunction

Dysfunction

Limited mobility

Limited mobility

Locking

Locking

Popping

Popping

Crepitus

Crepitus

Previous treatment

Previous treatment

Imaging

Imaging

Consults

Consults

Medication

Medication

Appliance: night guard, splints, braces, surgery

Appliance: night guard, splints, braces, surgery

Current medication

Current medication

Medical/dental history

Medical/dental history

Hospitalization

Hospitalization

Intubation

Intubation

Trauma

Trauma

Illness

Illness

Previous dental work

Previous dental work

Preexisting dental disease

Preexisting dental disease

Personal considerations

Personal considerations

Habits: clenching, bruxism, gum chewing, other

Habits: clenching, bruxism, gum chewing, other

Occupational history

Occupational history

Stress evaluation

Stress evaluation

Disability caused by TMD

Disability caused by TMD

TMJ EVALUATION

Measurement of mandibular range of motion

Measurement of mandibular range of motion

Click on opening or closing

Click on opening or closing

Crepitus upon opening or closing

Crepitus upon opening or closing

Limit of opening without pain

Limit of opening without pain

Excursion

Excursion

Overbite

Overbite

Overjet

Overjet

Open bite

Open bite

Deviation upon opening

Deviation upon opening

Deviation upon closing

Deviation upon closing

Dislocation upon opening

Dislocation upon opening

Dislocation upon closing

Dislocation upon closing

Pain in TMJ upon palpation intraorally

Pain in TMJ upon palpation intraorally

Pain in TMJ upon palpation extraorally

Pain in TMJ upon palpation extraorally

Palpation of muscles of mastication, 0 to 3 (0 normal, 1 slight, 2 moderate, 3 severe)

Palpation of muscles of mastication, 0 to 3 (0 normal, 1 slight, 2 moderate, 3 severe)

Masseter

Masseter

Temporalis

Temporalis

Lateral pterygoid

Lateral pterygoid

Medial pterygoid

Medial pterygoid

Resisted motion

Resisted motion

Opening

Opening

Right lateral

Right lateral

Protrusive

Protrusive

Closing

Closing

Left lateral

Left lateral

Auscultation and palpation of joint sounds

Auscultation and palpation of joint sounds

Laboratory studies: If suspected of ID/osteoarthritis (OA)

Laboratory studies: If suspected of ID/osteoarthritis (OA)

Imaging

IMAGING

TMJ imaging should be selected based on preliminary findings of the history and physical examination. Imaging of TMJ and associated structures can be used as adjunctive diagnostic tools to establish the presence or absence of pathology and stage of disease. It is recommended to obtain bilateral studies because of the high incidence of bilateral joint disease (AAOMS Parameters of Care, 2012).

a. Panoramic films are useful screening tools for most patients and will reveal gross abnormalities of the bony region of the TMJ. They are valuable tools in assessing the source of facial pain that is often confused with TMJ pain, such as dental infections, neoplasms, sinus pathology, and Eagle’s syndrome. Plain radiographs can assess condylar morphology and position of the condyle in the fossa.

b. CT scan can be used to assess bone abnormalities such as ankylosis, dysplasias, growth abnormalities, fractures, and osseous tumors. It is important to note that if a panoramic screen shows degenerative changes of the bone in the TMJ, axial CT may be needed. Three-dimensional (3D) CT is a valuable diagnostic tool for complex cases requiring major reconstructive surgery. When ordering a CT scan of the TMJ, thin-slice images with 3D reformatting should be requested. This will allow manipulation of the images and visualization of the bony component of the joint from any view. It will also maximize the diagnostic value of the proposed image and assist in surgical planning. Contrast is not needed for routine imaging of the TMJ unless the joint is infected and soft-tissue spread has occurred (AAOMS Parameters of Care, 2012).

If history and physical examination suggest ID of TMJ, MRI studies may be ordered. MRI can confirm the clinical suspicions of ID of the TMJ by showing disc position and determining whether the disc is reducing or nonreducing. Disc morphology can also be assessed on MRI and could be of great value in planning the surgical approach (AAOMS Parameters of Care, 2012).

It is recommended the that surgeon and radiologist have a prior discussion to assure a useful scan in which slices that are in the sagittal plane are perpendicular and coronal images are parallel to the medial and lateral axes of the condylar head. T1-weighted sagittal scans should be obtained in closed- and open-mouth views in the smallest slice thickness available. T2-weighted images are useful for showing joint effusion, whereas T1-weighted images are best for evaluating TMJ anatomy. Coronal images are useful for determining medial/lateral position of the TMJ disc and for assessing patterns of degenerative changes in the condylar head. The T2-sagittal and T2-coronal images are acquired only in closed-mouth position to shorten the time and stress on the patient (AAOMS Parameters of Care, 2012).

c. Arthrotomography. MRI has replaced arthrography; however, in selected cases, it is still used for identifying disc pathology. MRI really has become the standard for imaging the soft tissue of the TMJ, but dye-contrast arthrotomography can still provide excellent diagnostic images of ID. However, it is more technique sensitive and more difficult to perform. CT is also superior to various forms of plane tomography. CT images can be manipulated to the diagnostic advantage of the surgeon; this is not possible with conventional tomography.

d. Transcranial radiographs have also been suggested in the literature; however, the diagnostic value of this technique is poor because of angulation and distortion of the supporting structures.

e. Technetium 99 (Tc 99m): Advanced imaging techniques such as nuclear medicine scanning of the head may occasionally be required. Tc 99 scanning is useful in cases of condylar hyperplasia or osteochondroma where the treatment plan hinges on whether the lesion is actively growing. The affected bone will have increased uptake of dye.

f. Isotope bone scan: Radioactive isotope bone scans have a high sensitivity for detecting metabolic activity and inflammation. Increased vascularity on such a scan appears as increased isotope activity.

g. Diagnostic arthroscopy permits obtaining synovial fluid for analysis and specimen for biopsy (AAOMS Parameters of Care, 2012).

PATHOLOGY

PATHOLOGY

TMD is a collective term embracing all the problems involving to the TMJ and related musculoskeletal structures. The disease is characterized by deterioration of the articular cartilage, disc, synovium, subchondral bone, and (in rare instances) disc displacement. Histological evaluation of these joints suggests osteonecrosis. There are also secondary inflammatory changes that result from tissue damage in the joint. Several inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, neuropeptides, serotonin, and free radicals, have been isolated from fluid in symptomatic joints and may play a role in producing pain (de Leeuw, 2008a).

As explained previously, problems can arise from the joint itself or from muscles of the jaw. Injury to the jaw, TMJ, or muscles of the TMJ can cause pain and discomfort at the TMJ. Other possible causes include grinding or clenching of the teeth, dislocation of disc, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and stress.

ID and the usual coexisting osteoarthritis are considered to be the most common cause of serious TMJ pain and dysfunction. The prevalence of ID is not clearly defined, but it occurs most commonly in females. Women comprise about 80% of patients seeking treatment for joint pain. Average age of patients seeking surgical care is about 30 years.

Failure to find disc placement or OA in infants and very young children strongly suggests that the condition is not congenital but acquired. Joint overload also plays a role in development of OA in TMJ. In addition to overload, blunt force to the face or flexion–extension neck injuries may cause or aggravate ID/OA. Moreover, the repetitive loading of clenching and bruxing possibly are etiological factors. Genetic and metabolic factors may contribute by lowering the threshold for tissue damage from overloads or trauma and, therefore, may also be important factors in development of ID/OA. The relationship of the time of onset between ID and OA is not clear; however, it seems more plausible that ID precedes OA. It is also speculated that the causative event simultaneously initiates both ID and OA, and once the improper disc placement is present, ID almost certainly facilitates the progression of pathology, especially the development of bone changes in the condyle and temporal fossa (AAOMS Parameters of Care, 2012).

Myofacial Pain or TMD?

Myofacial pain disorders are the most common cause of pain in the head and neck region. Complex symptoms and frequent psychological factors often make these disorders difficult to treat. Once diagnosed, the treatment is usually effective if compliance is good. In myofacial pain, muscles of mastication are normally involved and the patient typically experiences a dull, unilateral, aching pain that increases with muscular use. Other complaints are headaches, otalgia, tinnitus, burning tongue, and difficulty hearing. It is important to note that myofacial pain is associated with pain over the TMJ without the palpable or audible click that is associated with most TMJ disorders. Stress also greatly contributes to this disease. Parafunctional habits such as bruxism, clenching, and excessive gum chewing can all contribute to muscle overload, fatigue, spasm, and pain (Turp, Hugger, & Sommer, 2007).

There are three diagnostic criteria for myofacial pain syndrome:

1. Presence of painful, firm bands of muscle or tendons otherwise known as trigger points

2. Pain complaints that follow known patterns of trigger points

3. Reproducible pain complaints with trigger points

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree