and Punkaj Gupta1

(1)

Department of Pediatrics Divison of Pediatric, Pulmonology and Sleep Medicine, University Of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock Arkansas, USA

Keywords

Neuromuscular diseasePediatricsNoninvasive ventilationMechanical ventilationNoninvasive weaningAbbreviations

ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

ARF

Acute respiratory failure

BIPAP

Biphasic positive pressure ventilation

BiPA

Bilevel positive pressure ventilation

CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

FiO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

IPPV

Invasive positive pressure ventilation

NPPV

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

NIV

Non-invasive ventilation

PICU

Pediatric intensive care unit

PaO2

Arterial partial pressure of oxygen

PaCO2

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

SpO2

Arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry

54.1 Introduction

The common etiologies of respiratory failure requiring chronic ventilatory support in children include neuromuscular diseases (NMDs), congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, spinal cord injury, craniofacial abnormalities, severe tracheobronchomalacia, chronic lung disease, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Prevalence of NMD is about 1 in 3,000. Positive-pressure ventilation is often used to provide respiratory support for children with acute respiratory failure (ARF) because it increases the tidal volume and therefore helps to recruit lung tissue and maximize lung volumes, reversing hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Mechanical ventilation (MV) can be delivered via positive-pressure breaths or negative-pressure breaths. Additionally, the positive-pressure breaths may be delivered noninvasively or invasively. Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is defined as the use of a mask or nasal prongs to provide ventilatory support through a patient’s nose and/or mouth. By definition, this technique is distinguished from those ventilatory techniques that bypass the patient’s upper airway with an artificial airway (endotracheal tube, laryngeal mask airway, or tracheostomy tube). To reduce the effect of complications associated with protracted invasive ventilation, investigators have explored the role of NIV in weaning patients from invasive ventilation. Noninvasive weaning involves extubating patients directly to NIV for the purpose of weaning to reduce the duration of invasive ventilation and, consequently, complications related to intubation. Use of NIV has seen increasing popularity in pediatric patients with both chronic respiratory failure and ARF of numerous etiologies [1].

Negative-pressure ventilation is an alternative form of NIV that uses a rigid cuirass that covers the chest and abdomen. Applied negative-pressure leads to diaphragmatic descent and ventilation, provided that the upper airway is stable. Modern pediatric machines are available, but they are relatively expensive and offer little clinical advantage over positive-pressure machines and thus are infrequently used for ARF or chronic respiratory failure.

The benefits of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) for ARF are being increasingly recognized in patients with chronic respiratory insufficiency. It has been applied to pediatric patients with a variety of respiratory disorders associated with impending ARF of almost any etiology, including pneumonia, pulmonary edema, postoperative respiratory decompensation in sleep apnea syndrome, status asthmaticus, neuromuscular weakness, airway obstruction (including laryngotracheal malacia), postextubation atelectasis, and chronic respiratory failure [2–7]. The success of this technique depends not only on the diagnosis of respiratory failure and patients’ characteristics but also on when the ventilation is started and the setting in which the patient is treated. A study in the state of Massachusetts in the United States found that the highest percentage of children requiring MV is no longer due to the chronic lung disease associated with premature birth but rather for reasons related to congenital and neurological disorders and NMDs [8]. This chapter focuses on positive-pressure ventilation via noninvasive interface in pediatric patients with ARF and chronic neuromuscular weakness.

54.2 Management of ARF in Children with NMD

Respiratory failure is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with slowly or rapidly progressive NMD. There are a wide variety of NMDs that can compromise respiratory functions, as summarized in Table 54.1. Depending on clinical onset of ARF, NMDs can be also classified as: (1) slowly progressive NMD with acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory failure, and (2) rapidly progressive NMD with acute episodes of respiratory failure. Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and inherited myopathies (e.g., Duchenne muscular dystrophy) are the most frequent slowly progressive NMDs in children.

Table 54.1

Neuromuscular diseases affecting respiratory functions

Myopathies |

Acquired myopathies |

Polymyositis, dermatomyositis |

Critical illness myopathy |

Toxic myopathy |

Hereditary myopathies |

Progressive muscular dystrophy |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Becker muscular dystrophy |

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy |

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy |

Myotonic dystrophy |

Congenital myopathies |

Myofibrillar myopathy, nemaline myopathy, central core diseases, myotubular myopathy |

Congenital muscular dystrophy |

Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy, Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy, merosin-positive congenital muscular dystrophy, rigid spine muscular dystrophy |

Metabolic myopathies |

Mitochondrial myopathy, glycogen storage disease type 2 |

Neuropathic disease |

Motor neuron disease |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

Poliomyelitis, post-polio syndrome |

Spinal muscular atrophy |

Paralytic rabies |

Peripheral neuropathies |

Guillain–Barre’ syndrome, chronic inflammatory demyelinating |

Polyneuropathy |

Critical illness polyneuropathy |

Unilateral or bilateral diaphragm paralysis |

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease |

Disorders of the neuromuscular junction |

Myasthenia gravis, congenital myasthenic syndrome, Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome |

Botulism, poisoning with curare and organophosphate |

When these patients develop chronic respiratory failure, long-term MV is the main therapeutic intervention to support their respiratory muscle function, increasing life expectancy and health-related quality of life. However, these patients are at high risk of developing acute exacerbations of respiratory failure. The potential causes of respiratory failure in patients with NMD include upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, atelectasis, cardiac failure secondary to cardiomyopathy and/or arrhythmia, sedative drugs, aspiration, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, and acute gastric distension associated with use of NIV.

54.3 Mechanisms Underlying ARF in NMD

In patients with slowly progressive NMD, ARF is caused by an imbalance between the respiratory load and muscle strength, resulting in ineffective alveolar ventilation and hypercapnia. In contrast, in patients with rapidly progressive NMD, such as myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and inflammatory myopathies, ARF is generally caused only by an acute and severe decrease in muscle strength, without necessarily the presence of triggers or other respiratory diseases.

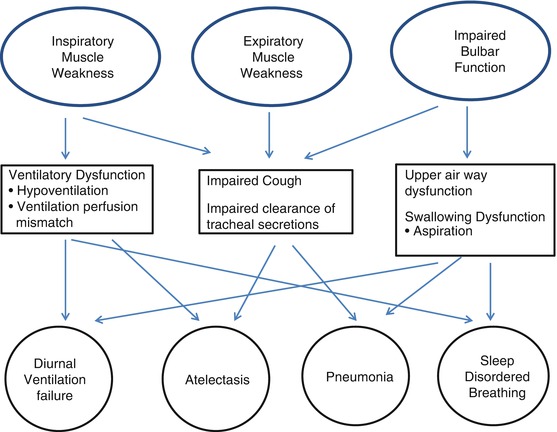

Respiratory muscle weakness results in a decline of the functional residual capacity of the lungs. This increases the work of breathing, and the reduction of lung volume alters ventilation/perfusion relationships, resulting in less efficient gas exchange. Weakness of expiratory muscles combined with inadequate lung inflation prevents effective coughing and airway clearance, altering airway resistance and increasing the risk of developing atelectasis and pneumonia [9]. Thus, hypoventilation, upper-airway obstruction, aspiration lung disease, secretion retention and lower airway infection, and the mechanical effects of progressive scoliosis are seen as a consequence of neuro muscular weakness (NMW). Bulbar muscle weakness (facial, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal muscles) can affect the ability to speak, swallow, and clear airway secretions, resulting in an increased likelihood of aspiration (Fig. 54.1)