INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Every practicing emergency physician over his or her career will see hundreds of patients with complaints of hip or knee pain that are unrelated to major trauma or an acute fracture. Discomfort and limitations to normal use in these areas are typically related to the minor trauma that occurs on a repetitive basis from performing routine daily functions or exercising. Athletes of all varieties are especially prone to these maladies, where strenuous activity transmits forces that are equivalent to three to five times the body weight directly to these major joints. Conversely, the problem of obesity similarly contributes to joint and supporting structural stress and pain.1

However, be alert to the various catastrophic processes that can mimic more mundane etiologies, including ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, epidural abscess, and septic joint (among others). Pay close attention to historical points, specific risk factors, abnormal vital signs, and physical findings to avoid making a life- or limb-threatening misdiagnosis.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND ANATOMY

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint (enarthrosis), allowing motion in all directions. The hip is similar to the shoulder in this capacity, but is much more sTable and relatively resistant to dislocation. The bones of the joint (femoral head, pelvic acetabulum) are strongly reinforced with a fibrocartilaginous labrum, a joint capsule, overlying ligaments, and numerous muscles.

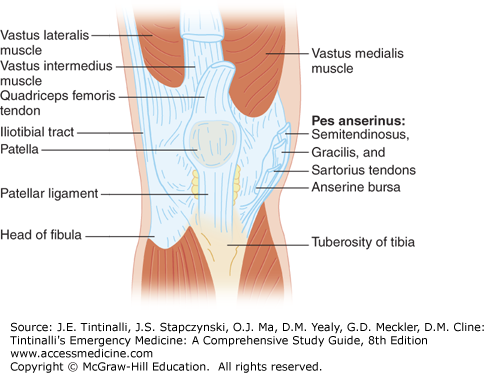

The knee is the largest synovial joint in the body and is relatively complicated in structure, comprising two distinct articulating groups: the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints. The patella floats above the main joint, attaching to the femur superiorly by the quadriceps tendon and inserting into the tibia inferiorly by the patellar ligament. The knee is stabilized internally by the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, and externally by the medial and lateral collateral ligaments. In addition, distal to the main joint, the fibular head attaches by ligaments to the proximal lateral tibia. The medial and lateral menisci are interposed between, and protect, the femoral and tibial condyles. Numerous muscles, tendons, bursa, and additional ligaments add to the complexity of the joint and serve as potential sources for pain and dysfunction (Figures 281-1 and 281-2).

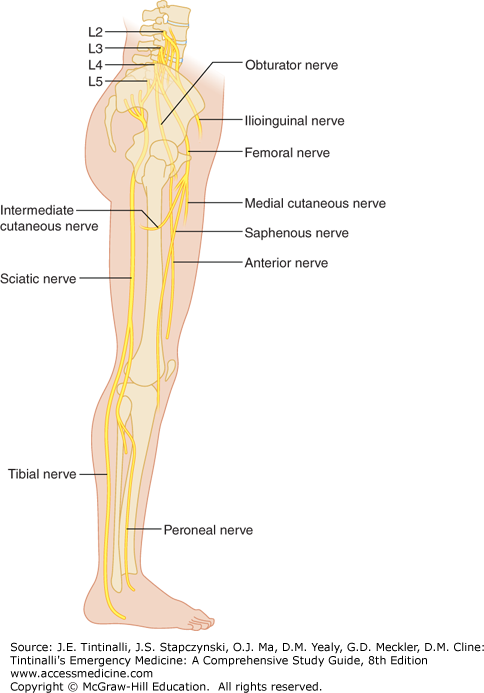

The femoral and sciatic nerves are the major nerves within the thigh (Figure 281-3). The femoral nerve is the largest branch of the lumbar plexus, and the sciatic is the longest nerve in the body, traveling posteriorly and supplying sensation to the hip joint through its articular branches. The femoral and obturator nerves also innervate the hip. The femoral nerve divides into anterior and posterior branches, with the posterior becoming the saphenous nerve and providing sensation to the lower leg. The anterior nerve supplies sensation to the anterior medial thigh by the medial and intermediate cutaneous nerves. The two major branches of the sciatic, the peroneal and tibial nerves, course through the posterior fossa of the knee, along with the popliteal artery and vein.

Pain in the area of the knee is not commonly referred to other sites, and knee pain is usually due to local pathology. However, referred pain from hip pathology is commonly felt in the buttocks, thigh, or groin; may extend to the knee; and may even travel to the foot. Pain felt in the hip and surrounding locations may be referred from pressure on the proximal nerve roots as they exit the lumbar and sacral spine. In the patient with appropriate risk factors, consider expansion or rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm as the cause of hip pain that is not otherwise explained by the history or physical examination, especially when there are no preexisting joint issues. Bedside US may exclude this life-threatening diagnosis. Other extra-articular sources of hip pain include intra-abdominal or pelvic tumors; diverticular, epidural, or psoas abscess; and the generally less worrisome diagnoses of herpes zoster or herniated lumbar disc.

DIAGNOSIS OF KNEE AND HIP DISEASES AND SYNDROMES

The majority of knee and hip problems can be diagnosed or excluded with a focused history and physical examination (Table 281-1).

Determine the location of the pain to narrow down the potential diagnosis. Determine the activities that bring on the pain. Complaints that the joint “gives out” or “buckles” generally are due to pain and reflex muscle inhibition rather than an acute neurologic emergency. This complaint may also represent patellar subluxation or ligamentous injury and joint instability. Poor conditioning or quadriceps weakness generally causes anterior knee pain of the patellofemoral syndrome; therapy should address this weakness. Locking of the knee suggests a meniscal injury, which may be chronic. A popping sensation or sound at the onset of pain is reliable for a ligamentous injury. A recurrent knee effusion after activity suggests a meniscal injury. Pain at the joint line of the knee (palpable indentation between distal femur and proximal tibia) suggests a meniscal injury. |

A suspected diagnosis obtained via history and physical examination is confirmed or ruled out by imaging. For the majority of soft tissue injuries or overuse syndromes, radiographs are not particularly useful unless a history of significant trauma or cancer exists. More sophisticated imaging is typically not needed for evaluation in the ED but may be indicated at follow-up or for selected ED patients on an individual basis. US can identify intra-articular or bursal effusions and soft tissue swelling and can localize muscle or tendon injuries. Normal comparison US views from the unaffected leg can be helpful. US is very helpful for the evaluation of popliteal cysts and arterial structures and will exclude deep venous thrombosis as a cause of pain and swelling.

Plain films are helpful in the evaluation of bony abnormalities such as severe arthritic changes and spurring, calcification derangements, and other inflammatory processes late in their courses. CT scan provides superior detail of osseous structures, will identify intra-articular loose bodies, and visualizes the early changes of osteonecrosis. Abnormalities of the labrum and joint capsule may also be seen. MRI, as the test of choice, precisely defines the anatomy of both the hip and knee and provides great detail for soft tissue and bony abnormalities. MRI is usually obtained on an outpatient basis. Although not frequently ordered from the ED, bone scans may be useful for the assessment of a variety of infectious and inflammatory processes, including avascular necrosis. Ultimately, arthroscopy of the knee and hip allows direct visualization of intra-articular lesions and simultaneous treatment.

SPECIFIC SYNDROMES AND DISEASES BY LOCATION

See Table 281-2 for a summary of the most important conditions.

| Diagnosis Category | Diagnosis | Pain Location |

|---|---|---|

| Nerve entrapment | Meralgia paresthetica Obturator nerve entrapment Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment Piriformis syndrome (sciatic nerve compression by piriformis muscle) | Anterolateral thigh pain or paresthesias Groin and inner thigh pain Groin pain Buttocks and hamstrings pain |

| Hip bursitis | Trochanteric bursitis Ischiogluteal bursitis Iliopectineal and iliopsoas bursitis | Hip pain when lying on side or with hip abduction and adduction Ischial pain Anterior pelvis and groin, hip extension |

| Knee bursitis | Pes anserine bursitis Prepatellar bursitis | Anterior medial knee pain Pain anterior to patella |

| Hip overuse syndromes | External snapping hip syndrome (coxa saltans) Fascia lata syndrome | Posterior lateral hip pain Lateral thigh pain |

| Knee overuse syndromes | Patellofemoral syndrome (runner’s knee) Medial plica syndrome Iliotibial band syndrome or snapping knee syndrome Popliteus tendinitis Patellar tendinitis (jumper’s knee) Quadriceps tendinitis Popliteal (Baker) cyst | Anterior knee pain, worse with prolonged knee flexion Anterior medial knee pain, knee snapping during repeated flexion/extension Pain over lateral epicondyles, or snapping when iliotibial band passes over femoral condyle Posterior lateral knee pain, worse on downhill exercise Inferior patellar or proximal patellar tendon pain Proximal patellar pain Posterior knee pain |

The psoas muscle is susceptible to the hematogenous spread of infection from distant sites because of its rich blood supply and proximity to overlying retroperitoneal lymphatic channels.2 Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen (80%); other less frequent pathogens include Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus aphrophilus, Proteus mirabilis, and enteric pathogens.

Symptoms include abdominal pain radiating to the hip, flank pain, fever, and limp. Presentation may be insidious. Other symptoms include nausea, weight loss, and malaise. To provoke pain, instruct the patient to perform forceful contraction of the psoas. Place your hand just proximal to the patient’s ipsilateral knee, and have the patient raise his or her thigh against your hand. Confirm the diagnosis by CT scan. Treatment includes antibiotics and surgical consultation for percutaneous (most commonly) or open drainage.2

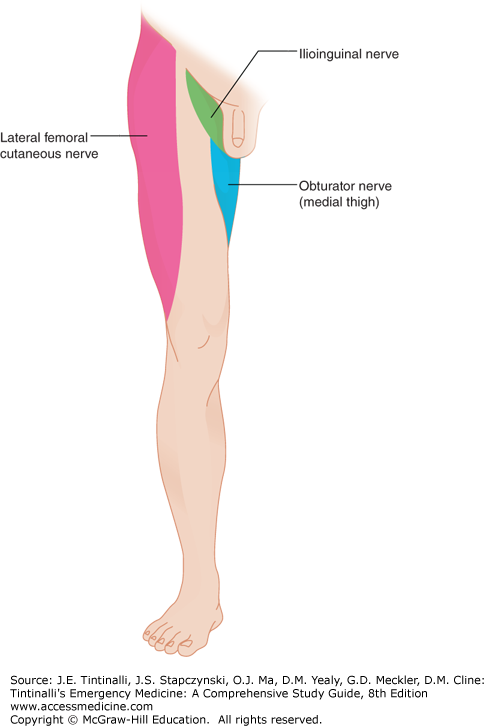

Meralgia paresthetica, or compressive inflammation of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, is the best known of the lower extremity nerve entrapment syndromes. The nerve enters the thigh under the inguinal ligament near the anterior superior iliac spine and is subject to a variety of minor, reoccurring traumatic events. The syndrome can be triggered by (among other causes) wearing tight belts, heavy tool belts, car seat belts, or corsets; pregnancy; certain sitting positions (i.e., on a riding lawnmower); focal trauma, including surgical interventions such as appendectomy or hysterectomy; and obesity. It has been reported in women with muscular thighs performing activities that require repetitive flexion/extension of the leg, such as cheerleading, and in runners. Symptoms include pain to the hip area, thigh, or groin along the distribution of the nerve (proximal anterior lateral aspect of the leg; Figure 281-4), burning or tingling paresthesias, and hypersensitivity to light touch. Pain may be worsened or reproduced during physical examination by tapping over the area of the anterior superior iliac spine. Those affected should limit the exacerbating activity and eliminate the source of the irritation. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local injections, weight loss, and (rarely) surgical excision of the nerve are other treatment options.3,4

Obturator nerve entrapment is typically a sequela of pelvic fractures or abdominal/pelvic surgery. Obturator nerve inflammation is generally sensed in the groin and down the inner thigh (Figure 281-4) and aggravated by movement of the hip. Exercise-induced medial thigh pain may be the predominant symptom. The nerve is entrapped in athletes due to the presence of a fascial band at the distal obturator canal or may be compressed due to pelvic hematomas or other masses. Surgery may be required for pain relief. Imaging studies are of limited value, but needle electromyography reveals the characteristic findings of chronic denervation. Local injection of lidocaine into the area of the nerve relieves the pain and associated reactive weakness and may make the diagnosis; however, the nerve block is both difficult to perform and rarely done in the ED.5

The ilioinguinal nerve arises from the lumbar plexus and passes through the psoas muscle, the transverses abdominal muscle adjacent to the anterior superior iliac spine, and the abdominal oblique muscles into the inguinal canal to innervate the groin and scrotum or labrum. Entrapment occurs due to hypertrophy of the abdominal wall musculature or pregnancy. Hyperextension of the hip produces pain and hypoesthesia in the distribution of the nerve, yielding groin pain.6

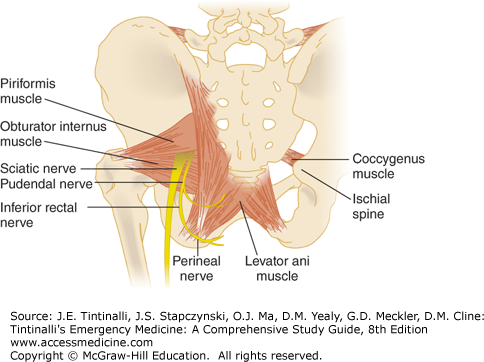

Compression of the sciatic nerve generally produces pain in the distal extremity, but irritation of the sciatic nerve from the piriformis muscle, referred to as the piriformis syndrome, causes pain in the area of the buttocks and hamstring muscles that is worsened by sitting, climbing stairs, or squatting (Figure 281-5). The clinician may palpate a tender mass over the piriformis muscle and elicit pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint or gluteal musculature. Hip flexion and passive internal rotation will exacerbate the symptoms. Imaging is useful only to rule out other conditions. Treatment is conservative.

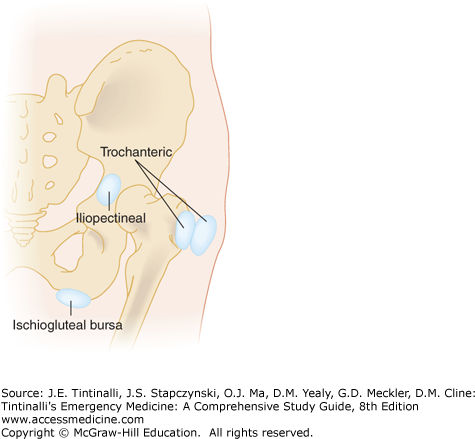

Bursae are self-contained flat sacs, lined with synovium, that reduce friction between tissues moving over each other in a repetitive fashion, such as ligaments, tendons, and bone. New bursae may form at any area that is subject to repeat irritation. Causes of bursal pain include inflammation (with repetitive minor trauma; rheumatologic disorders, such as psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis; and crystalline disease, such as gout or pseudogout) and infection. Certain bursae are more prone than others to these insults, and these produce symptoms in specific locations that the practitioner should recognize.

Inflammation may be very difficult to distinguish from infection, because both disorders share common symptoms and signs, with a significant overlap in diagnostic cell counts when bursal fluid is aspirated. A Gram stain positive for bacteria and a culture growing pathogens are definitive for infection and septic bursitis, but infection may be present in the absence of these findings. Occasionally, with trauma or prolonged inflammation, a bursa may end up communicating with a joint. Arthrocentesis is required in these circumstances or any other when a septic joint is suspected. The development of a draining sinus tract favors septic bursitis (see chapter 284, “Joints and Bursae”).

The trochanteric bursae lie between the gluteus maximus and the posterolateral greater trochanter, with a deep and superficial component (Figure 281-6). Female runners with a broad pelvis are prone to inflammation in this location. Inflammation is commonly seen in older women and can be a complication of rheumatoid arthritis. The patient complains of pain due to direct pressure when lying on the involved side, with activities where the hip is abducted (involving the deep bursa), and when adducted for the superficial component. Simple walking and climbing stairs aggravate the pain as well. Pain is revealed by palpation over the greater trochanter and resisted abduction or adduction of the hip.7,8

Bursitis from abnormal calcification is uncommon, but may affect the trochanteric bursa. Calcific bursitis is identified on plain radiographs or CT as a poorly marginated line that is clearly separated from the femoral cortex. Calcification may also form around tendons.

Ischiogluteal bursitis presents with pain over the ischial prominence (Figure 281-5), which thus is increased in the sitting position. “Weaver’s bottom” is a nickname for the inflammatory version of this bursitis, which is particularly exacerbated by sitting on a hard surface for long periods. As expected, this condition most often occurs in sedentary individuals. The bursa is also subject to focal, direct trauma. The bursa lies in close proximity to the sciatic nerve and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, predisposing to concomitant inflammation of these nerves and subsequent characteristic radicular pain.

The iliopectineal bursa is interposed between the hip joint and the iliopsoas muscle (Figure 281-6). Pain is located over the anterior pelvis and the groin on the affected side. The patient may reflexively assume a position of hip flexion and external rotation to aid in relief. On examination, extend the hip and palpate the area overlying the joint capsule to reproduce pain.9

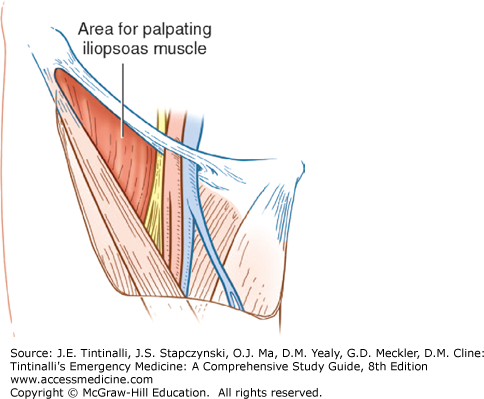

The iliopsoas bursa lubricates movement of the iliopsoas tendon over the lesser trochanter and is the largest bursa in the hip region. The patient complains of pain to extension of the hip, which is reduced by hip flexion. There may be tenderness over the middle third of the inguinal ligament in the area of the femoral pulse (Figure 281-7). This process may be confused with iliopsoas tendinitis, hernias, femoral aneurysms, adenopathy, or psoas abscess.10

The pes anserine (from the Latin for three-toed foot of the goose) bursa lies deep to the three tendons that insert on the medial aspect of the tibia below the knee joint—the gracilis, sartorius, and semitendinosus—and above the medial collateral ligament and medial femoral condyle (Figure 281-8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree