INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Injuries to the hip and femur are common, occurring most often in the elderly population secondary to falls. Hip fractures are a significant and costly public health concern. Age, race, and gender are important risk factors for hip injuries; the incidence is more than two times greater in women than in men.1

Morbidity and mortality from hip and femur fractures are due to complications from prolonged immobilization, with venous thromboembolism being the most common complication. Patients with hip fracture have a five- to almost eightfold increased risk of all-cause mortality in the first 3 months after the injury, and increased mortality persists for years afterward. Another significant portion of patients will have markedly decreased functional capacity. Advanced age, male gender, and comorbidities all increase mortality risk following hip fracture.2

This chapter discusses the diagnosis and ED management of fractures of the hip and proximal femur, fractures of the femoral shaft, and anterior and posterior hip dislocations. Fractures involving the femoral condyles are discussed in chapter 274, Knee Injuries.

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

For purposes of this chapter, we define the hip as the anatomic region including the head and neck of the femur to 5 cm distal to the lesser trochanter. The femoral shaft is the portion of the femur distal to the lesser trochanter, down to but not including the femoral condyles.

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the femoral head and the acetabulum. The fibrous capsule that surrounds the joint on all sides is quite strong, attaching proximally at the acetabulum and distally on the intertrochanteric line on the anterior surface. The joint capsule is weakest posteriorly where it attaches to the femoral neck. The femoral head and shaft are connected at the obliquely angled femoral neck. Blood is supplied to the femoral head mainly from the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries that form an extracapsular ring with branching retinacular arteries in the joint capsule. Therefore, intracapsular fractures can compromise blood supply to the femoral head. Less important blood supply includes branches of the obturator and gluteal arteries, with a small contribution from the foveal artery at the ligamentum teres.

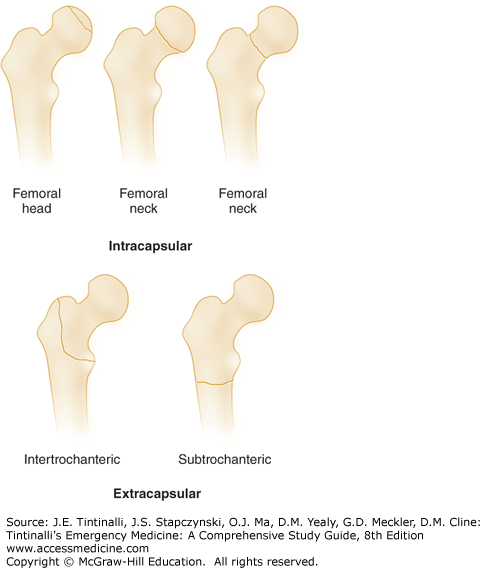

Hip fractures are classified as intracapsular (femoral head and neck) or extracapsular (trochanteric, intertrochanteric, and subtrochanteric). See Figures 273-1 and 273-2 and Table 273-1. The prognosis for successful union and restoration of normal function varies considerably with the fracture type. Most fractures occur in older patients with osteoporosis or other bony pathology secondary to systemic disease. Younger patients are more likely to have femoral shaft fractures or hip dislocation secondary to high-energy trauma.

| Fracture | Incidence/Demographics | Mechanism | Clinical Findings | Concomitant Injuries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral head | Isolated fracture rare; seen in 6%–16% of hip dislocations | Usually result of high-energy trauma; dashboard to flexed knee most common | Limb shortened and externally rotated (anterior dislocation); shortened, flexed, and internally rotated (posterior dislocation) | Closed head injury; intrathoracic and/or intra-abdominal injuries; pelvic fracture, knee injuries |

| Femoral neck | Common in older patients with osteoporosis; rarely seen in younger patients | Low-impact falls or torsion in elderly; high-energy trauma or stress fractures in young | Ranges from pain with weight bearing to inability to ambulate; limb may be shortened and externally rotated | Ipsilateral femoral shaft fracture |

| Greater trochanteric | Uncommon; older patients or adolescents | Direct trauma (older patients); avulsion due to contraction of gluteus medius (young patients) | Ambulatory; pain with palpation or abduction | — |

| Lesser trochanteric | Uncommon; adolescents (85%) > adults | Avulsion due to forceful contraction of iliopsoas (adolescents); avulsion of pathologic bone (older adults) | Usually ambulatory; pain with flexion or rotation | — |

| Intertrochanteric | Common in older patients with osteoporosis; rare in younger patients | Falls; high-energy trauma | Severe pain; swelling; limb shortened and externally rotated | Anemia from blood loss into thigh; concomitant traumatic injuries |

| Subtrochanteric | Similar to intertrochanteric; 15% of hip fractures | Falls; high-energy trauma; may also be pathologic | Severe pain; ecchymosis; limb shortened, abducted, and externally rotated | Vascular injuries, anemia/hypovolemic shock from fracture itself or other traumatic injuries |

In intracapsular fractures with displacement, blood supply to the femoral head may be compromised due to direct injury to the blood vessels, tension from the fracture, or compression secondary to a hemarthrosis. Urgent reduction of the fracture may restore blood flow, although avascular necrosis occurs in 15% to 35% of patients unless some of the capsular vessels remain intact.3 Extracapsular fractures less commonly cause vascular compromise.

CLINICAL FEATURES

History of a recent fall or motor vehicle crash suggests the possibility of hip fracture and other injuries. Falls should also prompt questioning about possible syncope, especially in the ill or elderly. Understanding the mechanism of injury can identify associated fractures, such as fractures of the pelvis or about the knee. Important historical factors, such as cancer, chronic kidney disease, or prolonged steroid use, increase the risk of osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, and pathologic fractures.

Patients with hip fracture or dislocation will typically have pain at the site of the injury, but may also report knee pain, groin pain, or pain at sites of other injuries. Determine the duration of immobilization to assess for dehydration, venous thrombosis, or rhabdomyolysis.

After the primary survey and stabilization, carefully examine the patient for deformities, shortening, rotation, lacerations, bruising, or instability of the limbs or tenderness of the pelvis or sacrum. Note any focal tenderness or crepitance. If no significant abnormalities are found, evaluate range of motion of the hips. If rotation of the hip with the leg in extension is painful, avoid other hip maneuvers. Identification of a hip or pelvic injury in a trauma victim should raise suspicion for concomitant intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, femoral shaft, knee, or urologic injuries. Perform a rectal exam if concern exists for concurrent spinal or pelvic injuries, including evaluation of the prostate in males.

Injuries to the hip and femur should also raise concern for damage to adjacent nerves and vasculature, especially the femoral and sciatic nerves and femoral blood vessels. Assess motor and sensory function of these nerves and their major branches (Table 273-2). Evaluate pulses distal to the site of injury, including popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibialis pulses. If concern exists for vascular injury, further testing should be performed and may include ankle-brachial indices, angiography, or duplex US.

| Nerve | Motor | Sensory |

|---|---|---|

Sciatic Common peroneal Tibial | Knee flexion Dorsiflexion of foot and toes Plantarflexion of foot and toes | Lateral lower leg, first web space of foot Posterior lower leg |

Femoral Anterior branch Posterior branch | Hip flexion Knee extension | Anterior and medial thigh Medial lower leg |

DIAGNOSIS

Consider radiographic evaluation of the pelvis and hips in all unconscious patients who have sustained multiple injuries or have a concerning mechanism for pelvic, hip, or lower extremity injury.

Include anteroposterior and lateral views of the hip in the initial radiographic evaluation. An anteroposterior pelvis view is also useful as it allows comparison of both sides. Conventional radiographs are estimated to be 90% to 98% sensitive for hip fractures.4 Other views may be requested by consulting orthopedists; in certain instances, additional views (e.g., Judet view) may allow better identification and detail of the acetabulum or femoral head and neck. Imaging of the femoral shaft or knee may also be necessary, following the adage to assess the joint above and the joint below the injury.

Pain with weight bearing in the face of normal radiographs should raise suspicion for occult fracture, especially at the femoral neck or acetabulum.5 MRI is highly sensitive (nearly 100%) for occult fractures and is also useful in identifying other injuries that may explain the patient’s symptoms. CT may be useful in identifying nondisplaced fractures not easily seen on conventional radiographs but is not as sensitive or accurate as MRI for occult fracture. Although bone scanning is sensitive for detecting occult fracture, neoplasm, and avascular necrosis, MRI has largely replaced it.4,5,6,7

HIP FRACTURES

Isolated femoral head fractures are uncommon and are typically associated with dislocations of the hip (Table 273-1). The signs and symptoms are often from the dislocation rather than from the fracture itself. They are usually best seen on radiographs obtained after reduction of a hip dislocation.

The standard anteroposterior and lateral views usually demonstrate the fragment adequately. Judet views or thin-cut CT scans are often recommended for further evaluation of the acetabulum and fracture fragmentation.

Treatment is to reduce the associated dislocation and then attain anatomic reduction of the fracture fragment (Table 273-3). See subsequent section on dislocations for further discussion. Management of concomitant life-threatening injuries due to high-energy trauma must take priority.

| Fracture | ED Management | Disposition and Follow-Up | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral head | Immediate orthopedic consultation; emergent closed reduction of dislocation; ORIF if closed reduction is unsuccessful | Admission to orthopedic or trauma service | AVN; posttraumatic arthritis; sciatic nerve injury; heterotopic ossification |

| Femoral neck | Orthopedic consultation; ranges from nonoperative to total hip arthroplasty | Admission to orthopedic service | AVN; infection; DVT and/or pulmonary embolus |

| Greater trochanteric | Analgesics; protected weight bearing | Orthopedic follow-up 1–2 wk; possible ORIF if displacement >1 cm | Nonunion rare |

| Lesser trochanteric | Analgesics; weight bearing as tolerated; evaluate for possible pathologic fracture | Orthopedic or PCP follow-up in 1–2 wk; admit or urgent follow-up for pathologic fracture | Nonunion rare |

| Intertrochanteric | Orthopedic consultation | Admit for eventual ORIF; may need preoperative testing and clearance by PCP or hospitalist | DVT and/or pulmonary embolism; infection |

| Subtrochanteric | Orthopedic consultation; consider Hare® or Sager® splint | Admit for ORIF | DVT and/or pulmonary embolism; infection; malunion (shortened limb); nonunion |

Prognosis is related to the severity of the initial trauma resulting in the dislocation and associated injuries, delay to reduction, and repetitive unsuccessful reduction attempts.8

Femoral neck fractures are most commonly seen among older adults with osteoporosis and occur more frequently in women than in men. Falls are the most common cause (90%), but stress or traumatic femoral neck fractures may be seen in younger patients (Table 273-1).9 There are multiple classification systems for femoral neck fractures, but it is most useful to describe them as displaced or nondisplaced. Femoral neck fractures are intracapsular, and blood supply to the femoral head may be disrupted.

The symptoms seen with femoral neck fractures range from complaints of mild pain in the groin or inner thigh in patients with an incomplete fracture, to moderate to severe pain in patients with displaced fractures. Patients with nondisplaced fractures may be somewhat ambulatory, whereas those with displaced fractures are typically unable to bear weight at all. Examination findings can be subtle in nondisplaced fractures, while displaced fractures are quite evident with the leg held in external rotation, abduction, and shortened (Figure 273-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree