INTRODUCTION

With nearly 10% of the population developing some sort of hernia during their lifetime, this is among the most common of surgical problems.1 Hernias are classified by anatomic location, hernia contents, and the status of those contents (e.g., reducible, strangulated, or incarcerated).2

A hernia is called reducible when the hernia sac itself is soft and easy to replace back through the hernia neck defect. A hernia is incarcerated when it is firm, often painful, and nonreducible by direct manual pressure. Strangulation develops as a consequence of incarceration and implies impairment of blood flow (arterial, venous, or both). A strangulated hernia presents as severe, exquisite pain at the hernia site, often with signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction, toxic appearance, and, possibly, skin changes overlying the hernia sac. A strangulated hernia is an acute surgical emergency. This chapter discusses hernias in adults. Hernias in children are discussed in chapter 130, “Acute Abdominal Pain in Infants and Children.”

ANATOMY OF COMMON HERNIAS

Seventy-five percent of all hernias occur in the inguinal region, making it the most common form of hernia, with two thirds of these being of the indirect type (Figure 84-1). Although there is a clear male predilection, inguinal hernias are also the most common hernias in women. Inguinal hernias present as a groin mass. Typically the mass has been present for some time, but may have recently become larger or the patient may have begun to develop symptoms of incarceration or strangulation. The differential diagnosis for a groin mass is somewhat broad and includes, in addition to hernia, hidradenitis, other abscess, sebaceous cyst, lymphoma, hydrocele, varicocele, femoral hernia, and femoral aneurysm. Thankfully, the physical examination for most hernias is fairly straightforward. Bedside US can be very helpful in the identification of an inguinal hernia if the diagnosis remains in question (Figure 84-2). One study reported 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity of bedside emergency US for the diagnosis of groin hernia.3

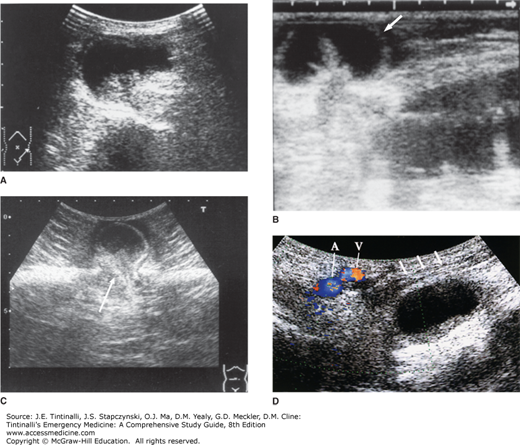

FIGURE 84-2.

Incarcerated hernia. A. An incarcerated femoral hernia is demonstrated as a small-bowel segment herniated through the femoral canal. B. In an incarcerated incisional hernia, a small-bowel segment (arrow) is demonstrated as herniated through a small orifice in the abdominal wall. Dilated small-bowel loops are evident proximal to the incarceration. C. In an umbilical hernia, a herniated small-bowel segment is demonstrated within the fluid space in the hernia sac. The segment was softly strangulated at the hernia orifice (arrow) formed by a defect of the fascia and was easily reduced by manipulation in this case. D. An incarcerated obturator hernia is demonstrated deep in the femoral region. It locates posterior to the pectineus muscle (arrows) and medial to the femoral artery (A) and vein (V). [Reproduced with permission from Ma OJ, Mateer JR, Blaivas M (eds): Emergency Ultrasound, 2nd ed. Copyright © 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies, All rights reserved. Chapter 9, General Surgery Applications, Common Abnormalities, Incarcerated Hernia. Figure 9-16.]

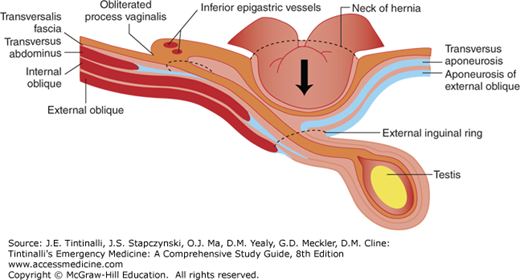

A direct inguinal hernia passes directly through a weakness in the transversalis fascia in the Hesselbach triangle. Hesselbach triangle is constructed with the lateral border of the inferior epigastric arteries, a medial border with the rectus sheath, and an inferior border of the inguinal ligament (Figure 84-3).4

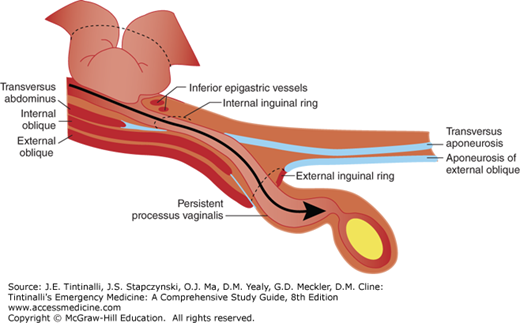

The hernia sac from an indirect inguinal hernia passes from the internal to the external inguinal ring through the patent process vaginalis, and then to the scrotum (Figure 84-4).

Ventral hernias develop as a result of a defect in the anterior abdominal wall and can be either spontaneous or acquired. They are typically characterized by their anatomic location as epigastric, umbilical, incisional, or hypogastric (rare; Figure 84-5).5

Incisional hernias account for up to 20% of all abdominal wall hernias. They are often the result of excess wall tension or inadequate wound healing. They are also associated with surgical wound infections. Risk factors for the development of incisional hernias include obesity, age, wound infection, and medical conditions (i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) that increase intra-abdominal pressure.6 Incisional hernias can become quite large and produce symptoms varying from discomfort to extrusion of abdominal contents to incarceration and strangulation. Despite primary repair, the recurrence rate can be as high as 50%.

The adult form of umbilical hernia is largely acquired and due to medical conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure, including ascites, pregnancy, and obesity. Although strangulation is unusual in most patients, those with chronic ascites (i.e., cirrhotics) are at risk for umbilical hernia strangulation, rupture, and death from peritonitis.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree