Wendy L. Biddle Hepatitis is a general term meaning inflammation in the liver. Hepatitis has numerous causes, which can include viruses, alcohol, medications, autoimmune disease, and metabolic defects. Inflammation that continues for 6 months is considered chronic liver disease (CLD) and can eventually result in cirrhosis, characterized by scarring and death of hepatocytes or liver cells and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). CLDs are major causes of morbidity and mortality. Liver failure and the need for transplantation can occur if the cirrhosis progresses. An evaluation of data from 1988 to 2008 demonstrated that the prevalence rates for most of the major causes of CLD have remained stable except for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) which has been increasing.1 From 2005 to 2008 the prevalence of CLD was 14.78%. In 2007 2.6 million people were diagnosed with CLD.2 In 2013 there were more than 15,000 people older than age 18 on the waiting list for liver transplantation, with the largest group being ages 50 to 64 years. The most common diagnoses for liver transplantation are chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, followed by NAFLD and alcoholic cirrhosis.3 Most viral hepatitis is attributed to five main groups of viruses that attack the liver: hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV; also known as hepatitis delta virus and occurring only as a coinfection with HBV), and hepatitis E virus (HEV). The features of the viruses are described in Table 137-1. Other viruses may cause a secondary hepatitis that never becomes chronic and resolves with the viral infection. Acute viral hepatitis can range in severity from a clinically asymptomatic infection to fulminant hepatic failure and death (rare). Chronic viral hepatitis is considered to be the presence of virus at least 6 months after initial exposure and can range in severity from mild disease with minimum inflammation to cirrhosis, liver failure, and need for transplantation. TABLE 137-1 Features of Viral Hepatitis The prevalences of chronic hepatitis B and C have been stable for the past 20 years.1 There are many risk factors, including intravenous drug use, high-risk sexual behavior, and tattoos. Viral hepatitis is common among inmates of correctional facilities. There are multiple prison-based programs in place that include HAV and HBV vaccinations, needle exchanges, risk reduction, and management strategies aimed at decreasing transmission among inmates. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published recommendations for prevention and control of viral hepatitis in incarcerated people in the United States.4 HAV, HBV, and HCV all cause inflammation by affecting the hepatocytes, which causes acute disease with similar symptoms but differing levels of pathogenicity.5 HAV, an RNA virus identified over 20 years ago, is a common cause of acute viral hepatitis in the United States. In 2010, there were 1670 new cases in the United States, and worldwide it is responsible for approximately 1.5 million cases each year.6 The highest incidence occurs in areas of low socioeconomic status, poor sanitation, and poor access to clean drinking water, including Africa, Asia, and Central America. In developing countries, HAV accounts for up to one third of all cases of viral hepatitis. There have been intermittent outbreaks in the United States, most recently in 2014. HAV is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, through person-to-person contact, through the ingestion of contaminated food or water, and through blood. The virus can survive for months in fresh and salt water. Ingestion of shellfish from polluted water is another means of transmission. HAV can be found in liver cells, bile, stool, and blood and has an incubation period of 2 to 6 weeks. The incidence of hepatitis A has decreased in the United States because of vaccination recommendation and use.7,8 All strains of this virus belong to the same serotype; as a result, HAV immune globulin provides worldwide protection. The vaccination involves an injection followed by a booster, which can provide immunity for 20 years. The virus can be inactivated by boiling for 1 minute or by exposure to formaldehyde, chlorine, or ultraviolet radiation. Patients are most infectious in the late incubation period because the virus excretes a large amount of virus 11 days before the antibodies appear in the blood. Clinical symptoms appear approximately 4 weeks after exposure, but more than 75% of adults and 70% of children younger than 6 years are asymptomatic when they are infected. This contributes to the easy spread of the virus.8 The virus can be found in the stool 2 to 3 weeks before and up to 1 week after the development of clinical jaundice. Despite the presence of HAV in the liver, viral shedding in feces, viremia, and infectivity rapidly decrease once jaundice appears. Therefore, most patients are contagious when they are asymptomatic and are no longer contagious by the time they become diagnosed with jaundice. An important exception involves neonates, who can be infectious for up to 6 months after clinical jaundice develops. It is an acute disease, and, rarely, relapses can occur 30 to 90 days after the primary illness. There are rare cases when extrahepatic manifestations, including vasculitis, nephritis, myocarditis, encephalitis, and others, occur. HAV infection never progresses to chronic hepatitis.8 Hepatitis B is endemic worldwide, especially in Asia, where the carrier rate is estimated to be 1 in 4. In the United States, 1 in 10 Asian Americans have chronic hepatitis B, and of those, 1 in 4 will die of liver failure or liver cancer. Worldwide it is estimated that 400 million people have chronic HBV, with the highest rate in China.9 It is less prevalent in the United States, and new infections are decreasing, but it was estimated that there were between 700,000 and 1.4 million people infected with chronic HBV in 2014.10 Five percent to 10% of those infected are expected to develop chronic HBV.5 The migration of Asians to the United States is contributing to the public health burden because it is estimated that up to 14% are carriers of chronic HBV.9 There were 3050 reported new cases of HBV in the United States in 2010 for an incidence of reported acute HBV of 0.9 per 100,000.6 However, because HBV can be asymptomatic, the estimated rate of new cases is 10 times higher, or 19,764 newly infected persons in 2013.10 In Asia and Africa, HBV infection is seen mostly among newborns and young children and is spread by vertical transmission from mother to child. People with chronic HBV have an increased lifetime risk of cirrhosis and HCC.11 It is recommended that individuals in high-risk groups (Box 137-1), including all who were born in Asia or have direct family members born in Asia, be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for HBV. In North America and Europe, hepatitis B is more common among adolescents and young adults and is spread by sexual contact and percutaneous exposure. Other risk factors are listed in Box 137-1. It is estimated that up to 40% of those infected with HBV will develop significant complications including cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. Almost 5000 people die of HBV-related cirrhosis or HCC annually. The number of new cases of hepatitis B reported has declined each year since 1985. A safe and effective vaccine against HBV was introduced in 1982.12 Recommendations to prevent transmission of HBV include universal vaccination of infants beginning at birth, screening of all pregnant women to prevent perinatal infection, and immunoprophylaxis of infants born to HBsAg-positive women, which indicates infection. All children and adolescents not vaccinated need to be immunized, as do unvaccinated adults at risk of infection.11 Hepatitis B can present a clinical picture similar to that of the other subtypes, with a severity that can range from asymptomatic to fulminant and fatal liver failure; it can progress to CLD and possibly cirrhosis and HCC. HBV can be found in blood, tears, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, saliva, vaginal secretions, and seminal fluid. HBV is transmitted parenterally, by sexual contact, and perinatally. Heterosexual contact with a person infected with HBV is the most common mode of transmission, followed by injection drug use, homosexual activity, and vertical transmission from mother to child at the time of birth. Transmission from blood transfusions is rare in the United States because of extensive blood transfusion screening processes. HBV is not transmitted through the fecal-oral route or by arthropod vectors. Compared with the general population, health care workers, especially surgeons, phlebotomists, and dialysis nurses, and the spouses of infected persons are at an increased risk for contracting hepatitis B.13 Hepatitis C, the number one cause of cirrhosis, HCC, and liver transplantation, has reached epidemic proportions in the United States; an estimated 4 million people are infected and anti-HCV seropositive (prevalence of 1.68%), and 2.7 to 3.9 million are chronically infected.1 These estimates are likely to be low because the homeless, incarcerated, and hospitalized are not taken into account. Chronic HCV affects 12% to 31% of incarcerated persons, which results in substantial morbidity and risk of premature death. Worldwide, this disorder has also reached epidemic proportions, with an estimate of 200 million people infected.14 Of those in the United States with chronic HCV, over 130,000 are children under the age of 19 years.15 Approximately 75% of people with HCV are “baby boomers,” born between 1945 and 1965. They are five times more likely to be infected with HCV than the rest of the population. Fortunately, new infections with HCV in the United States are uncommon; the primary cause of the approximately 850 new acute clinical cases that occurred in 2010 was likely injection drug use.6 Estimates predict that 25% of people with chronic HCV will develop cirrhosis approximately 30 years after initial infection. Hispanics and African Americans have higher rates of HCV infection than whites. There appears to be greater disease and fibrosis progression, and the mortality rate is almost doubled.16 HCV, first identified in 1989, is a single-stranded RNA genome with a high rate of replication (1012 virions/day) and mutation. These characteristics lead to chronic infection, making it difficult to treat. At least six strains and multiple subtypes of the virus have been identified. Genotypes 2 and 3 respond better to treatment than does genotype 1, but 70% of people in the United States have genotype 1.17 Once a person is infected with HCV, the body initiates humoral and cellular mechanisms. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that approximately 75% of patients with HCV develop chronic infection. It is rare to see fulminant hepatic failure with acute HCV. The 25% who cleared the virus may have had a strong cellular immune response to HCV. Ineffective cellular immune responses lead to inflammation and damage in the liver. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV occur when humoral immune responses are continually stimulated. These can involve the skin, kidney, and nerves. Factors associated with rapid disease progression and cirrhosis include older age at time of infection, alcohol abuse, male gender, and coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).18 HCV has been transmitted through blood transfusions given before July 1992, receipt of clotting factor concentrates produced before 1987, chronic hemodialysis, any injection of illegal drugs, and intranasal drug use (sharing needles or straws). There is no evidence that arthropod vectors transmit HCV. Other possible risk factors include tattoos, manicures or pedicures, and body piercings. These practices are not regulated and should be considered possible risk factors, especially if there have been multiple exposures or the work is done in questionable environments. Data from other countries have shown an association with some of these factors and HCV infection, but studies in the United States have not shown an association. Health care workers and emergency medical personnel are at risk from needle sticks, sharps, or mucosal exposure to HCV-positive blood, although the rate of transmission is low. Sexual transmission may be responsible for up to 20% of new cases, but the overall rate is believed to be less than 5%. Those with multiple partners have a two- to five-times higher risk of acquiring HCV through sexual contact. Long-term partners of a person with chronic HCV should be tested every 5 years. The rate of vertical transmission from mother to child during delivery is approximately 5%. Certain subgroups are believed to have an especially high rate—for instance, 20% of those on hemodialysis, and even higher rates in prisoners. Coinfection of HCV and HIV is becoming more prevalent, creating unique challenges in management. The prevalence of hepatitis C among HIV-infected people is estimated at 15% to 30%.18 HDV is a defective RNA virus that requires coinfection with HBV for replication and is considered to be the most severe form of viral hepatitis. Of the 350 million people worldwide with chronic HBV, 5 % are coinfected with HDV.19 Several genotypes are known. It can be transmitted with HBV or may superinfect an individual who is already infected with HBV. It is transmitted parenterally through injection drug use and, rarely, through sexual contact. Perinatal transmission is rare and can be prevented through HBV prophylaxis. When it is seen in the Mediterranean region, HDV is endemic with HBV. In nonendemic areas such as the United States, HDV is associated with percutaneous exposure and blood transfusions. HDV is not transmitted through the fecal-oral route or by casual contact. During the past two decades, HDV circulation has decreased because of the use of HBV vaccine; however, the challenge of migration of infected persons from endemic areas continues to be a major problem.19,20 HEV is another RNA virus with four known human genotypes that has been responsible for large outbreaks in developing countries. It is often considered an important cause of acute hepatitis in Africa and Asia. This virus has a short incubation period of 15 to 60 days and usually results in a self-limited disease in an immune-competent host. There are groups that are at risk for severe disease and possible chronicity. Similar to HAV, HEV is enterically spread, most commonly by the ingestion of contaminated water. Areas endemic for HEV infection are Asia, northeast Africa, the Middle East, and Mexico, with up to 70% prevalence. In the United States, up to 20% of blood donors are seropositive for HEV. Prevalence is highest in states that have large producers of swine. Infection during pregnancy can lead to liver failure and death, especially during the third trimester, with mortality rates as high as 15% to 20%.21 Alcoholic hepatitis is a common and life-threatening cause of liver failure. This is a type of toxic liver injury associated with excessive alcoholic consumption on a chronic basis, usually 10 years or longer. In the United States, alcoholism is the one of the most common cause of cirrhosis. It is estimated that 10% to 35% of heavy drinkers develop alcoholic hepatitis. Studies suggest that an increased risk of cirrhosis occurs with ingestion of 10 to 20 g of alcohol a day in women and 20 to 40 g a day in men. Additional factors that increase the risk of alcoholic hepatitis include a genetic predisposition, environment, age when person started consuming alcohol, and body mass index higher than 25 in women and 27 in men. One drink of 10 g of alcohol is equal to 10 ounces of beer (5% ethanol), 3 to 4 ounces of wine (12% ethanol), or 1 ounce of hard liquor (40% ethanol, 80 proof).22 Recent evidence suggests that the drinking pattern may play a role and that daily drinking increases the risk compared with drinking less frequently. It was suggested that recent alcohol intake and not lifetime consumption could be a strong predictor of alcoholic cirrhosis.23 The excessive alcohol might lead to fat and inflammation of the liver, which can lead to cirrhosis. NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a spectrum of chronic disorders associated with the metabolic syndrome, is the most common CLD in the United States. The prevalence of NAFLD steadily increased from 5% in 1988 to 11% in 2008. It now accounts for 75% of CLDs in the United States. These increases correspond with increases in obesity (33%), visceral obesity (51%), type 2 diabetes (9%), insulin resistance (35%), and hypertension (34%). In addition, obesity is an independent predictor of NAFLD.1 There is a 10% to 20% incidence of NASH in those who have NAFLD. NASH is more serious because it is characterized by the development of inflammation (steatohepatitis) and scarring of the liver that can progress to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and failure. NASH is now the third most common cause of cirrhosis and is expected to be the most common reason for liver transplantation by 2020.24 NASH may be a part of the metabolic syndrome. Abdominal obesity, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes are associated with increased liver fat content, and insulin resistance is proposed to be the cause of the liver’s storing too much fat.25 A strong predictor of fatty liver and progression to NASH is obesity, especially central obesity. In addition, certain races have a higher risk of NAFLD; these include, in decreasing order of risk, East Asian Indians, Hispanics, and Asians. Caucasians and African Americans have less of a risk.24 Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a rare reaction associated with common medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antimicrobial agents. Half of all cases of acute liver failure are caused by drug hepatotoxicity, and it is thought that there is a genetic predisposition to DILI. Some drugs produce a predictable, dose-related injury, such as with acetaminophen, but most reactions are unpredictable. These reactions usually occur in one of two patterns: (1) an allergic reaction that occurs within 6 weeks of initiation of the drug, such as with phenytoin (Dilantin); or (2) a metabolic reaction that occurs with up to 1 year of continuous use, such as with isoniazid.26 More than 800 therapeutic agents, including prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, nutritional supplements, and herbal remedies, have been implicated in DILI. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases has created the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Since its inception in May 2004, more than 889 cases have been documented. The top offending drugs were amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and minocycline.27 A thorough drug history should include information about recent and past exposure to therapeutic agents, supplements, and herbal products. Details about the patient’s occupation and work environment as well as the use of herbal preparations and “traditional” medications should be obtained.26

Hepatitis

Definition and Epidemiology

![]() Physician specialist consultation and referral are indicated for patients with newly diagnosed hepatitis.

Physician specialist consultation and referral are indicated for patients with newly diagnosed hepatitis.

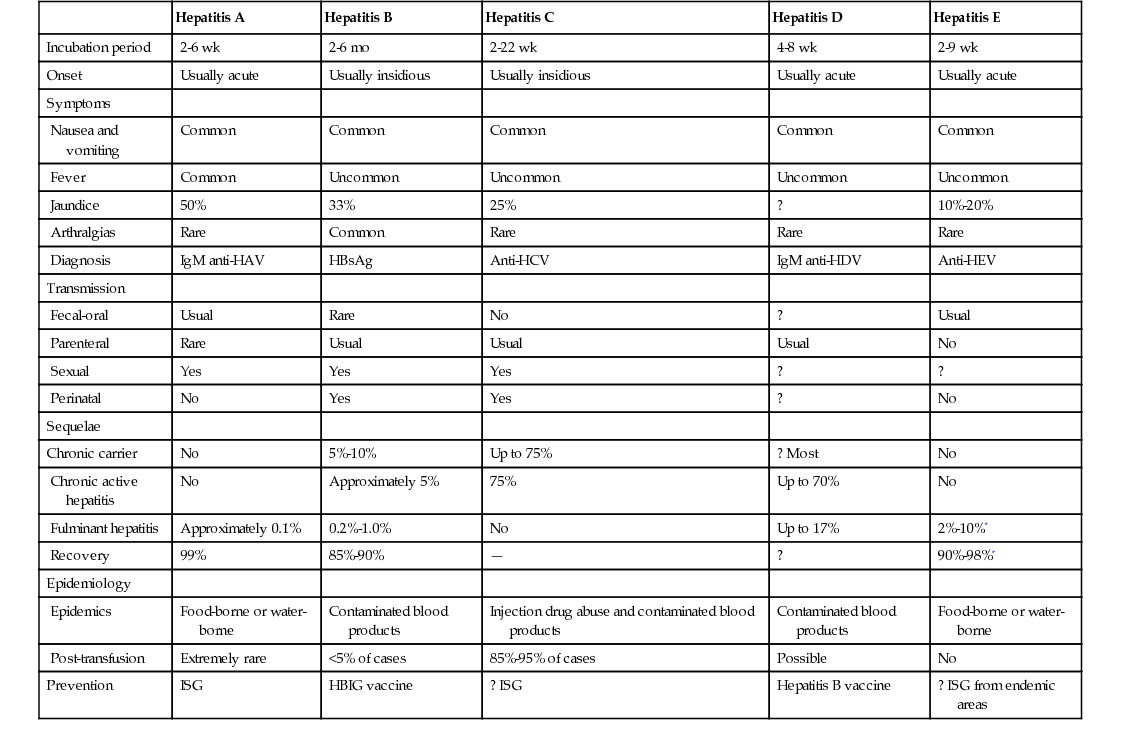

Viral Hepatitis

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis E

Incubation period

2-6 wk

2-6 mo

2-22 wk

4-8 wk

2-9 wk

Onset

Usually acute

Usually insidious

Usually insidious

Usually acute

Usually acute

Symptoms

Nausea and vomiting

Common

Common

Common

Common

Common

Fever

Common

Uncommon

Uncommon

Uncommon

Uncommon

Jaundice

50%

33%

25%

?

10%-20%

Arthralgias

Rare

Common

Rare

Rare

Rare

Diagnosis

IgM anti-HAV

HBsAg

Anti-HCV

IgM anti-HDV

Anti-HEV

Transmission

Fecal-oral

Usual

Rare

No

?

Usual

Parenteral

Rare

Usual

Usual

Usual

No

Sexual

Yes

Yes

Yes

?

?

Perinatal

No

Yes

Yes

?

No

Sequelae

Chronic carrier

No

5%-10%

Up to 75%

? Most

No

Chronic active hepatitis

No

Approximately 5%

75%

Up to 70%

No

Fulminant hepatitis

Approximately 0.1%

0.2%-1.0%

No

Up to 17%

2%-10%*

Recovery

99%

85%-90%

—

?

90%-98%*

Epidemiology

Epidemics

Food-borne or water-borne

Contaminated blood products

Injection drug abuse and contaminated blood products

Contaminated blood products

Food-borne or water-borne

Post-transfusion

Extremely rare

<5% of cases

85%-95% of cases

Possible

No

Prevention

ISG

HBIG vaccine

? ISG

Hepatitis B vaccine

? ISG from endemic areas

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Drug-Induced Liver Injury

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Hepatitis

Chapter 137