INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

This chapter discusses the ED presentation, evaluation, and treatment of acute and chronic liver disease as well as fulminant liver failure. Specific entities addressed in this chapter include viral and toxic hepatitis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and complications of cirrhosis including coagulopathy, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, and hepatic encephalopathy. Cholecystitis and biliary colic are addressed in chapter 79, “Pancreatitis and Cholecystitis.” Variceal bleeding is addressed in chapter 75, “Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding.”

Liver disease is associated with many ED complaints: abdominal pain, vomiting, shortness of breath, altered mental status, GI bleeding, and even nonspecific malaise can all be attributed to malfunction of the liver. Globally, hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E are major public health problems. About two billion people are infected with hepatitis B and 150 million with hepatitis C, and cancer and cirrhosis resulting from these infections account for about 3% of deaths worldwide.1 Cirrhosis is the 12th leading cause of death in the United States, and hepatitis C is the leading cause of cirrhosis in the United States, followed by alcoholic liver disease.2 Acute, or fulminant, liver failure is uncommon and is caused primarily by acetaminophen poisoning (46%), with hepatitis B being the most common infectious cause.3

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Acute hepatitis is caused by an infectious, toxic, or metabolic injury to hepatocytes. The initial injury leads to inflammation, cellular death, and eventual scarring in the liver. In chronic disease, liver parenchyma is replaced by fibrous tissue, which separates the functioning hepatocytes into isolated nodules. This disruption of the normal tissue structure can become severe and lead to the central characteristics of liver failure: loss of metabolic and synthetic function at the cellular level, progressive development of portal hypertension, ascites formation, and portal-systemic shunting at the gross level.

The liver’s synthetic functions include the production of coagulation and anticoagulation factors. The liver is responsible for production of the vitamin K–dependent clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X; proteins C and S; and other elements of the clotting and thrombolytic processes.4 Inadequate production of these clotting factors makes uncontrolled bleeding one of the life-threatening features of liver disease and a potentially dramatic complication of hepatic failure.

Portal hypertension is increased hydrostatic pressure in the portal vein and its feeder vessels, caused by resistance to blood flow through the cirrhotic liver. It eventually causes esophageal and gastric varices and portal-systemic shunting. The increased hydrostatic pressure in the intraperitoneal veins, hypoalbuminemia, and poor renal management of sodium and water lead to ascites in the cirrhotic patient. Ascites can cause respiratory compromise and lead to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), which occurs when normal flora translocate across an edematous bowel wall into the peritoneum. Bacteremia and infection of preexisting ascitic fluid ensue.5

Encephalopathy is a pivotal characteristic of chronic liver disease and is a hallmark of liver failure. Ammonia is often presumed to be the cause of confusion and lethargy in encephalopathic patients, but in fact, the pathophysiology is not completely understood. In cirrhosis, portal hypertension allows ammonia formed by colonic bacteria to enter the general circulation through portal-systemic shunting. Large intestinal protein loads, such as a high protein meal or GI bleeding, fuel this process. Although levels of ammonia do not reliably correlate with mental status, it is reasonable to think of ammonia as a contributing factor to alterations in mental status. In fulminant liver failure, cerebral edema and increased intracranial pressure can develop. In this end-stage state, loss of autoregulation of cerebral blood flow, ammonia-related edema, and a systemic inflammatory response are all thought to contribute to this deadly complication.6

Jaundice can be present in any stage of liver disease. Jaundice is caused by elevated levels of bilirubin in the circulation, leading to bile pigment deposits in the skin, sclerae, and mucous membranes. Hyperbilirubinemia can occur for one of three reasons: overproduction, inadequate cellular processing, or decreased excretion of bilirubin. Another way to think about this is prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic jaundice. Prehepatic jaundice is caused by any form of hemolysis, including inborn errors of bilirubin metabolism, which overwhelm the liver’s ability to conjugate bilirubin. Viral infection and ingested toxins are typical causes of hepatic jaundice. When hepatocytes necrose, the liver’s ability to conjugate bilirubin is impaired, and the level of unconjugated bilirubin rises in the blood. Unlike prehepatic and hepatic jaundice, which present with elevated unconjugated or indirect bilirubin, posthepatic jaundice produces a rise in conjugated bilirubin. Typical causes of post-hepatic jaundice are a pancreatic tumor or a gallstone in the common bile duct. Parasitic infestation and biliary atresia are rare causes in the United States but are more common in other parts of the world.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Clinical features of hepatitis are listed in Table 80-1.

| Acute Hepatitis | Chronic Disease/Cirrhosis | Acute Liver Failure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Nausea/vomiting/diarrhea | + | ± | + |

| Fever | + | – | – |

| Pain | + | ± | ± |

| Altered mental status | – | ± | + |

| Bruising/bleeding | – | ± | + |

| Physical examination | |||

| Jaundice | + | + | + |

| Hepatomegaly | + | – | ± |

| Ascites | – | + | + |

| Edema | – | + | – |

| Skin findings (bruising, vascular malformations) | – | + | + |

| Lab abnormalities | |||

| Elevated ALT/AST | + | + | ± |

| AST/ALT >2 | + | ± | ± |

| Elevated PT/INR | – | ± | + |

| Elevated ammonia | – | ± | + |

| Low albumin | – | + | + |

| Direct bilirubinemia | – | + | ± |

| Indirect bilirubinemia | + | + | ± |

| Urobilinogen | + | + | + |

| Elevated blood urea nitrogen/creatinine | – | – | ± |

| Radiologic findings | |||

| Ascites | – | + | + |

| Fatty liver | + | – | – |

| Cirrhosis | – | + | + |

At ED presentation, a chief complaint of jaundice, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, pruritus, inappropriate bruising or bleeding, or altered mental status should raise the question of liver disease. In the history of present illness, pay attention to onset of symptoms after eating out or after ingestion of acetaminophen (in one-time overdose or chronically high doses), mushrooms, or raw oysters. Note the duration of symptoms to characterize acuity. Past medical history can identify comorbidities or risk factors for liver disease. Risk factors include chronic hepatitis, transfusion of blood products, positive human immunodeficiency virus status, frequent use of pain medications, or depression. Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are risk factors specific to NASH. High-risk medications include acetaminophen and acetaminophen-containing pain medications, vitamin A, isoniazid, propylthiouracil, phenytoin, and valproate, as well as a variety of herbal remedies.7 Statins raise concern for hepatic toxicity but are rarely implicated in significant liver injury. Three percent of patients taking statins have mild transaminase elevations; clinically significant hepatotoxicity is rare.8 A social history positive for injection drug use, chronic alcohol abuse, sexual promiscuity, or travel to countries with endemic parasitic liver diseases represents increased risk for liver disease.

The review of systems in the patient with suspected liver disease can identify important signs and symptoms. Cholestasis causes white (acholic) stools and brown or tea-colored urine. Stools can be black or bloody from variceal or other GI bleeding. Patients may notice yellow skin or sclerae, indicating elevated bilirubin. Ascites can increase abdominal girth or cause shortness of breath, and portal hypertension leads to generalized weakness, encephalopathic changes in mental status, and lower extremity edema. Lightheadedness or near-syncope can result from intravascular depletion and abnormalities in renal sodium and water excretion.

A number of findings on physical examination are hallmarks of liver disease. Liver enlargement and tenderness with or without jaundice are characteristic of acute hepatitis. Chronic liver disease is accompanied by a number of physical findings, including sallow or jaundiced complexion, extremity muscle atrophy, Dupuytren’s contracture, palmar erythema, cutaneous spider nevi, distended abdomen with a fluid wave, enlarged veins on the surface of the abdomen (caput medusae), and asterixis. Extraordinary bruising or other signs of bleeding diathesis can be seen in liver failure.

ACUTE, CHRONIC, OR FULMINANT HEPATIC DISEASE

Liver disease can be categorized as acute, chronic, or fulminant. Accurately differentiating the acuity and severity of the disease process guides appropriate evaluation, treatment, and disposition.

Acute hepatitis typically presents with nausea, vomiting, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. The patient with acute hepatitis can also have fever, jaundice, bilirubinuria, and an enlarged, tender liver. The most common causes are viral infection and toxic ingestion. Alcohol and acetaminophen are the most common toxic causes.

Patients with chronic hepatitis display evidence of long-standing hepatocellular damage. Cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension complain of abdominal pain and/or distention, abnormal bleeding (bruising, bleeding gums, epistaxis, blood in the stool), and lower body edema. They may also exhibit signs of infection, encephalopathy, ascites, and electrolyte derangement. Skin examination may reveal spider nevi, caput medusae, and other manifestations of abnormal shunting of blood to surface vessels.

Liver failure is the potential final common pathway for both acute and chronic liver disease. If there is a delay in seeking medical attention or a rapid acute course, fulminant liver failure can be the presenting disorder. For cirrhotic patients, the transition to liver failure is marked by the advent of coagulopathy, encephalopathy, abnormal fluid shifts, and hepatorenal syndrome.

Hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus are the most prevalent forms of viral hepatitis encountered in the ED. Hepatitis A virus is transmitted by fecal-oral contamination. Although it is popularly associated with improper food handling or oyster consumption, the most common transmission occurs from asymptomatic children to adults. Implementation of the hepatitis A vaccine in children has dramatically decreased overall rates of infection. Hepatitis A virus infection has an incubation period of 15 to 50 days, followed by a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and malaise. About a week into the illness, patients may note dark urine (bilirubinuria). A few days later, they develop clay-colored stools and jaundice. Hepatitis A virus does not have a chronic component, and death from hepatic failure is rare.9

Hepatitis B virus is transmitted sexually, by blood transfusion, by contaminated needles, and by perinatal transmission. Incubation period is 1 to 3 months, and patients can be infectious for 5 to 15 weeks after onset of symptoms if they clear the infection. Individuals who develop chronic disease will remain infectious indefinitely. Chronic infection occurs in only 6% to 10% of patients who contract hepatitis B virus as adults, whereas 90% of infants and 30% of children under the age of 5 progress to chronic status, which underlines the importance of vaccination of infants and women of childbearing age.10 In the acute phase of hepatitis B virus, presentation to the ED is similar to that for hepatitis A virus, including complaints of malaise, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice.

Hepatitis C virus transmission occurs primarily through exposure to contaminated blood or blood products. In contrast to hepatitis A virus and hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus is most often asymptomatic in the acute phase of infection, and >75% of patients advance to the chronic stage. The rate of progression to liver failure varies and depends on the natural course of the virus and cofactors such as alcoholism and human immunodeficiency virus. Along with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus is one of the most common causes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Of the patients who develop chronic hepatitis C virus, 1% to 5% will die of either cirrhosis or liver cancer.11

Hepatitis D virus is uncommon and is typically seen in people with preexisting chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatitis D superinfection can result in a rapidly progressive or fulminant form of liver disease that carries a high short-term mortality rate. This variety of infection is most commonly associated with injection drug use.11

Acute illness with liver function test abnormalities also occurs with infection by other hepatotropic viruses such as cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Coxsackie virus, and Epstein-Barr virus. These agents are unlikely to cause clinically significant hepatitis in an otherwise healthy host.

A toxic insult to the liver can cause acute hepatitis and/or fulminant liver failure. The most common of these is acetaminophen overdose. Acetaminophen accounts for >40% of liver failure cases in the United States and one third of deaths secondary to toxic ingestion. Patients develop nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. They may also give a history of an acute overdose of acetaminophen or chronic use of one or more acetaminophen-containing pain medicines. Up to 28% of patients with acetaminophen overdose will develop liver failure. The likelihood of liver failure depends on time from ingestion to presentation, the dose ingested, and the baseline health status of the patient.12 Tylenol overdose is reviewed more completely in chapter 190, “Acetaminophen.”

In addition to acetaminophen, there are a variety of prescription medications (antibiotics and statins prominent among them), herbal remedies, and dietary supplements that have been associated with acute hepatitis and liver failure. The list of prescription medications that have been implicated in liver disease is so long that it is prudent to refer to a pharmaceutical database to identify a potential culprit when toxic insult is suspected. Some of the most common herbal remedies that have been implicated in hepatic injury are listed in Table 80-2.

| Herbal Remedy | Application | Nature of Injury |

|---|---|---|

| Black cohosh (Actea racemosa/cimiifuga racemosa) | Menopausal symptoms | Hepatic necrosis and bridging fibrosis |

| Chaparral (Larrea ridentate) | Antioxidant, health tonic | Cholestasis, chronic hepatitis, cholangitis, cirrhosis |

| Comfrey (Symphytum) | Broken bones, wound healing, reduce joint inflammation | Hepatic veno-occlusive disease |

| Echinacea (E. angustifolia, E. pallida, E. purpurea) | Respiratory infections, fever, immune booster | Acute cholestatic autoimmune hepatitis |

| Kava (Piper methysticum) | Anxiolytic, sleeping aid | Acute and chronic hepatitis, cholestasis, fulminant hepatic failure |

| Kombucha “mushroom” tea | Weight loss, increasing T-cell count, well-being, antiaging | Acute liver failure, hepatitis, acute renal failure with hyperthermia and lactic acidosis |

| Ma huang (Ephedra sinica) | Weight loss | Acute hepatitis |

| Mistletoe (Viscum album) | Hypertension, insomnia, epilepsy, asthma, infertility, urinary disorders | Acute hepatitis |

| Noni juice (Morinda citrifolia) | Health tonic | Subacute hepatic failure, acute hepatitis |

| Prostata (Serenoa repens); saw palmetto | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | Cholestatic hepatitis |

| Senna (Cassia angustifolia) | Laxative | Acute hepatitis, acute cholestatic hepatitis, acute liver failure |

| Skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis) | Sedative, anti-inflammatory | Hepatic veno-occlusive disease, cholestasis, hepatitis |

| St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) | Anti-depressant | Cytochrome P-450 induction, serotonin syndrome |

| Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) | Sedative, anxiolytic | Hepatitis |

Alcoholic liver disease can range from asymptomatic, reversible fatty liver to acute alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or a combination of acute and cirrhotic features. The diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease carries a 35% 5-year survival rate. If a patient has asymptomatic liver disease (i.e., fatty liver seen on imaging), but the patient’s drinking continues and acute alcoholic hepatitis develops, the mortality can be much higher.13 A history of consistent heavy alcohol use (mean intake at presentation of 100 grams or more) is thought to be required for development of significant alcoholic liver disease.14 However, information is often difficult to elicit from the patient or family, and the patient may have stopped drinking before ED presentation. Other nonhepatic features of alcohol abuse, such as malnutrition, stocking-glove neuropathy, pityriasis rosea, and cardiomyopathy, can be clues to alcohol-induced liver disease.

Mushroom poisoning is an uncommon but important cause of acute hepatitis with a high risk of liver failure. Amanita phalloides (“death cap”) is the most lethal of the more than 50 types of mushrooms that are toxic to humans. For detailed discussion, see chapter 219, “Mushroom Poisoning.”

Most patients live for years with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, NASH, or alcoholic hepatitis without symptoms. During the asymptomatic period, normal liver parenchyma is being gradually replaced by scar tissue, and hepatic disease can manifest as mild transaminase elevation or, in cases of NASH and alcoholic hepatitis, as an incidental finding of fatty liver on abdominal imaging studies. When a critical amount of liver parenchyma is replaced by fibrotic tissue, symptoms of cirrhosis develop, such as abdominal pain, ascites, SBP, general weakness resulting from electrolyte derangement, or altered mental status due to hepatic encephalopathy.

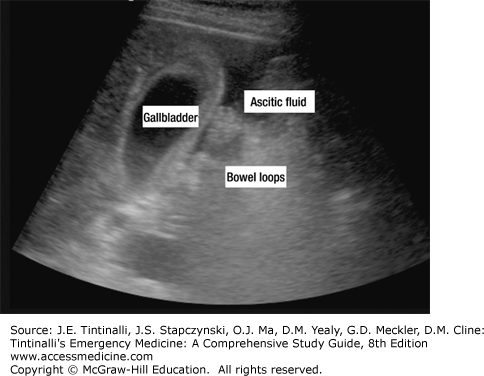

One of the hallmarks of cirrhosis, ascites causes a protuberant abdomen, and a fluid wave is produced on physical exam. Intra-abdominal fluid can displace the diaphragm upward and produce sympathetic pleural effusion with the possibility of respiratory compromise. Smaller amounts of ascites can be difficult to identify on examination; bedside ultrasound can be particularly helpful in patients in whom the presence of ascites is uncertain (Figure 80-1).