HEART MURMURS

LILA O’MAHONY, MD, FAAP

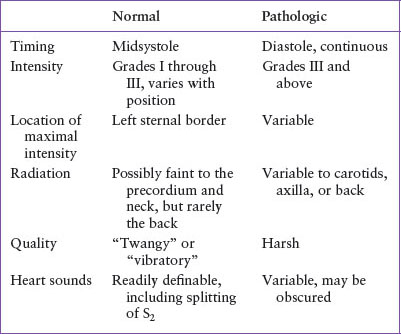

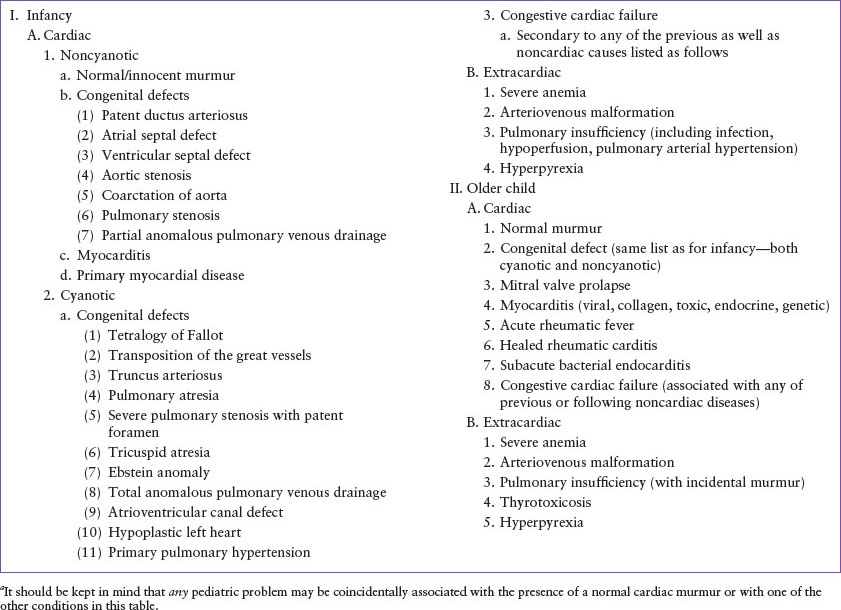

A heart murmur is the audible vibration of turbulent blood flow through the cardiovascular system. It can be normal or abnormal, congenital or acquired and upward of 90% of children will have an audible murmur at some point in their life. Fortunately, the vast majority of murmurs have no clinical significance and less than 1% is due to congenital heart defects (CHDs). Murmurs without clinical significance are referred to as “normal,” “flow,” “functional,” or “innocent”; whereas, abnormal murmurs, commonly referred to as “pathologic,” are clinically significant, often associated with structural heart defects and/or dysfunction and can lead to acute cardiopulmonary compromise (Table 31.1). A wide variety of cardiac and extracardiac conditions can be associated with heart murmurs (Table 31.2).

When evaluating a newly identified murmur in the emergency department (ED), the primary objective is not to diagnose a cardiac lesion, but to determine whether the murmur is clinically significant and if so, whether the murmur indicates that the child has significant heart disease that requires intervention or consultation by a pediatric cardiologist.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

History

Unless the patient is in extremis, a focused history is always the starting place and the examiner should include questions related to cardiac disease or dysfunction.

Infant specific

Infant specific

History of abnormal in utero ultrasound findings?

History of abnormal in utero ultrasound findings?

Significant prenatal and maternal history? (Advanced maternal age, maternal diabetes, intrauterine alcohol and drug/medication exposure as well as intrauterine infections are all associated with increased risk of CHD)

Significant prenatal and maternal history? (Advanced maternal age, maternal diabetes, intrauterine alcohol and drug/medication exposure as well as intrauterine infections are all associated with increased risk of CHD)

Easily fatigues, sweats, difficulty breathing, or skin color changes with feeding?

Easily fatigues, sweats, difficulty breathing, or skin color changes with feeding?

History of poor growth?

History of poor growth?

Child >1 year

Child >1 year

Tires easily when playing? Daily activities limited by fatigue or breathing difficulties? Does the child squat after walking? Climb stairs? Have cyanotic “spells”?

Tires easily when playing? Daily activities limited by fatigue or breathing difficulties? Does the child squat after walking? Climb stairs? Have cyanotic “spells”?

All patients

All patients

Has the murmur been identified previously? What were the findings?

Has the murmur been identified previously? What were the findings?

Is there a history of cardiac surgery?

Is there a history of cardiac surgery?

Recent illness, sore throat, upper respiratory infection, or fevers?

Recent illness, sore throat, upper respiratory infection, or fevers?

Weight gain or loss? Edema? Hypertension? Chest pain? Syncope? Joint symptoms?

Weight gain or loss? Edema? Hypertension? Chest pain? Syncope? Joint symptoms?

Family history of sudden death in children, congenital malformations, or heart disease/defects in children?

Family history of sudden death in children, congenital malformations, or heart disease/defects in children?

Examination

The evaluation should consist of a complete physical examination with special attention to the cardiovascular system and associated signs of cardiac dysfunction or compromise.

General Assessment

First, determine the cardiopulmonary stability of the patient following Pediatric Advanced Life Support guidelines (see Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation). Specific attention should be paid to the child’s skin color, presence or absence of cyanosis, mental status, work of breathing, and perfusion. Vital signs should be obtained including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. Vital sign abnormalities may be the first indication for further and/or emergent cardiopulmonary evaluation. For example, lower extremity blood pressures are normally measured 10 to 40 mm Hg higher than upper pressures and an elevated systolic blood pressure in the upper compared to the lower extremities may indicate a coarctation or obstruction of the aorta; hyperthermia may be associated with infectious etiologies or contribute to high blood flow state contributing to nonpathologic flow murmur whereas hypothermia may be associated with cardiogenic shock. Finally, oxygen desaturation that does not improve with supplemental oxygen may indicate cardiac pathology, and it has been shown that in the neonatal period pulse oximetry screening increases the detection of life-threatening CHD. Finally, infants and children with pre-existing or congenital heart disease may have abnormal oxygen saturations. Always ask their caregiver or parent what is normal for their child.

Precordial Examination

Inspect for left- or right-sided chest bulge which could indicate cardiac hypertrophy or dilation, palpate for thrills and clicks and points of maximal impulse, listen carefully for the heart sounds and adventitial sounds. If present, the third and fourth sounds, opening snaps, valve-associated clicks, pericardial rub, and unusual rhythms can be confused for murmurs and therefore are possible confounding factors in the precordial evaluation.

Murmur Characteristics

The range of characteristics will be briefly defined here:

Timing and duration: Is the murmur systolic, diastolic, or continuous? Early, mid, late, or throughout (holosystolic) the specific cardiac cycle?

Timing and duration: Is the murmur systolic, diastolic, or continuous? Early, mid, late, or throughout (holosystolic) the specific cardiac cycle?

Intensity (loudness): Graded from barely audible (grade I) to accompanied by a palpable thrill (grade IV) to audible with stethoscope off the chest (grade VI).

Intensity (loudness): Graded from barely audible (grade I) to accompanied by a palpable thrill (grade IV) to audible with stethoscope off the chest (grade VI).

Shape: Describes the murmur’s change in intensity over the cardiac cycle. Common terms used to characterize these volume flow patterns are plateau (constant intensity), crescendo, decrescendo, and crescendo–decrescendo (diamond shaped).

Shape: Describes the murmur’s change in intensity over the cardiac cycle. Common terms used to characterize these volume flow patterns are plateau (constant intensity), crescendo, decrescendo, and crescendo–decrescendo (diamond shaped).

TABLE 31.1

CHARACTERISTICS USUALLY ASSOCIATED WITH A MURMUR

Quality: Common terms used are musical, blowing, rumbling, harsh, vibratory, twang, soft, rough, grating, and click.

Quality: Common terms used are musical, blowing, rumbling, harsh, vibratory, twang, soft, rough, grating, and click.

Pitch: Described qualitatively as low (associated with low pressure gradient), medium, or high (associated with high pressure gradient).

Pitch: Described qualitatively as low (associated with low pressure gradient), medium, or high (associated with high pressure gradient).

Location and radiation: Location is the point of maximum intensity (upper, lower, middle left, or right sternal margin; apex; midclavicular or axillary line). Radiation refers to the area of maximal sound transmission (back, neck, axilla, or throughout entire precordium).

Location and radiation: Location is the point of maximum intensity (upper, lower, middle left, or right sternal margin; apex; midclavicular or axillary line). Radiation refers to the area of maximal sound transmission (back, neck, axilla, or throughout entire precordium).

Variation with maneuvers: An innocent murmur’s intensity often changes significantly with change in position, such as from supine to sitting or vice versa. Two important exceptions are hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and mitral valve prolapse (MVP), both of which have intensity changes based on position and are both pathologic.

Associated Signs and Symptoms

Skin Color. Central cyanosis (see Chapters 16 Cyanosis and 107 Pulmonary Emergencies) is diffuse and is best differentiated from peripheral cyanosis by involvement of the tongue. Central cyanosis due to a cardiac lesion may be differentiated from cyanosis due to pulmonary disease by administering 100% oxygen to the child while monitoring pulse oximetry. Those with pulmonary disease may improve their oximetry reading while those with cardiac lesions often will not. In older children, if clubbing of the distal fingers is present; cyanosis is probably chronic and persistent.

TABLE 31.2

CONDITIONS THAT MAY BE ASSOCIATED WITH PRESENCE OF A CARDIAC MURMURa

Other Skin Findings. Note midline surgical scars, look for petechiae, including in the conjunctivae and under the fingernails. Check for erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules. Severe pallor related to marked anemia may be associated with high output cardiac failure.

Potential Signs of Cardiac Failure. (See Chapter 94 Cardiac Emergencies)

Edema: More likely to be dependent and pitting in cardiac disease. In the preambulant child, dependent edema may be best appreciated along the posterior trunk and periorbital areas, rather than the lower extremities.

Edema: More likely to be dependent and pitting in cardiac disease. In the preambulant child, dependent edema may be best appreciated along the posterior trunk and periorbital areas, rather than the lower extremities.

Neck veins: Notable distention infrequent. Evaluate with the patient lying flat or propped at a 45-degree angle.

Neck veins: Notable distention infrequent. Evaluate with the patient lying flat or propped at a 45-degree angle.

Respiratory effort: Tachypnea, grunting, subcostal retractions, tracheal tug, and orthopnea. Listen for crackles and wheeze, usually symmetric compared to primary lung disease which is often asymmetric.

Respiratory effort: Tachypnea, grunting, subcostal retractions, tracheal tug, and orthopnea. Listen for crackles and wheeze, usually symmetric compared to primary lung disease which is often asymmetric.

Organ enlargement: Palpate for a soft, engorged liver, particularly the left lobe, which becomes palpable early in right-sided congestive heart failure (CHF). Check for splenomegaly.

Organ enlargement: Palpate for a soft, engorged liver, particularly the left lobe, which becomes palpable early in right-sided congestive heart failure (CHF). Check for splenomegaly.

Remaining Examination

Joints:

Joints:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree