Chapter 36 Head Trauma

Head trauma and brain injury are not always synonymous. Differentiating between the two is important when considering assessment and care of patients with traumatic injuries. Head injuries usually present with more visible symptoms such as lacerations or deformities, while traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) may be present in a patient who appears neurologically intact. TBIs can range from mild to severe. Early diagnosis and intervention are paramount in minimizing adverse outcomes.1

Brain injury is a contributing factor in one third of all injury deaths. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1.7 million people sustain a TBI annually.2 Of these, 52,000 die, 275,000 are hospitalized, and 1.365 million (nearly 80%) are seen in emergency departments.2 TBI is most common in three age groups—birth to 4 years, 15 to 19 years, and over 65 years—with falls being the leading cause.2 Motor vehicle crashes are the second leading cause but are responsible for the most deaths.2

Eighty percent of TBIs are classified as mild, but the effects can be long lasting and life changing. It has been estimated that 20% of military personnel involved in combat during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have sustained a TBI.1 Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and personality changes have been linked to mild TBI.3–5

Physical Assessment of the Head-Injured Patient

Glasgow Coma Scale

The GCS allows health care providers to perform a brief examination of level of consciousness in a precise, consistent manner. The GCS quantifies the eye opening, verbal responses, and motor responses of a patient with TBI to a set of standardized stimuli. Scoring is based on the patient’s best response to stimuli. If necessary, noxious stimuli are used to elicit a response. For more information on using the GCS, refer to Chapter 25, Neurologic Emergencies.

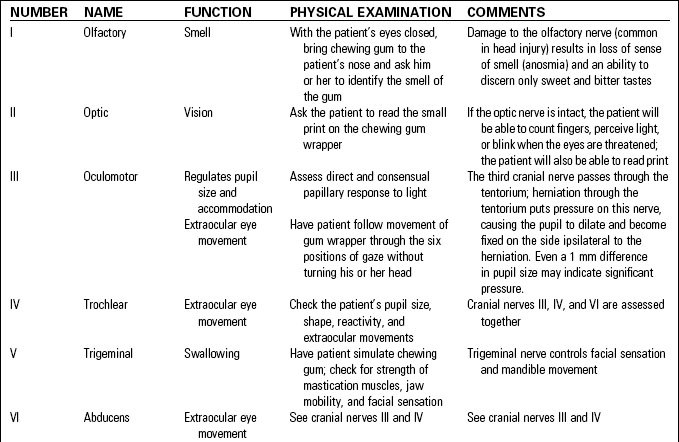

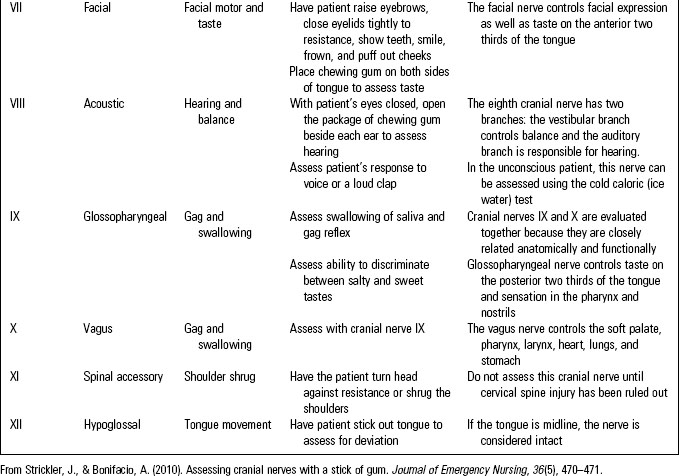

Cranial Nerve Assessment

There are 12 cranial nerves. Table 36-1 summarizes the functions and assessment of the cranial nerves.

Pupillary Assessment

• Pupils normally constrict when exposed directly to light.

• Light shined into one pupil causes the other pupil to constrict as well (consensual response).

• Allow at least 10 seconds between assessment of each eye for consensual response to diminish.

Up to 20% of the population normally has slightly unequal pupils (anisocoria), highlighting the need for careful and ongoing assessment of pupillary response.6

• Fixed, pinpoint pupils indicate pons involvement or the use of opiates.

• A dilated, fixed pupil (unilateral) indicates (early) third cranial nerve involvement and possible transtentorial herniation.

• Bilateral, fixed pupils indicate severe brainstem injury and possible brain death. (Pupils also may be fixed and dilated in certain reversible conditions and toxic exposures.)

• Ptosis (a drooping eyelid) indicates third cranial nerve impairment.

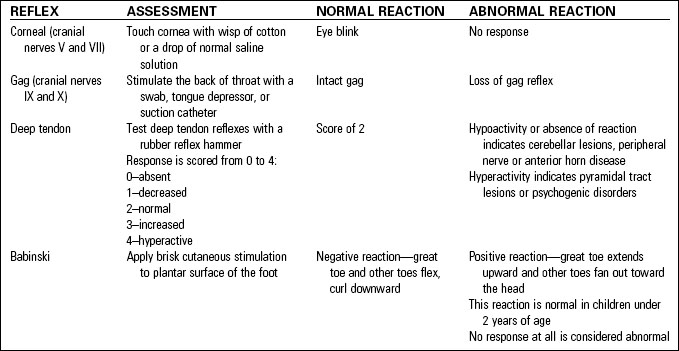

Reflex Assessment

Assessment of the various reflexes is summarized in Table 36-2.

If present, abnormal posturing can be elicited using verbal, tactile, or noxious stimulation.

• Abnormal flexion (Fig. 36-1): Arms flex, wrists flex, and legs and feet extend. Abnormal flexion indicates a lesion above the midbrain.

• Abnormal extension (Fig. 36-2): Arms extend, wrists flex, and legs and feet extend. Abnormal extension indicates brainstem herniation.

Diagnostic Procedures

Angiography

Cerebral angiographic studies are the gold standard for diagnosing cerebrovascular abnormalities, but their use is limited in the acute care setting. However, if a patient presents with neurologic symptoms and a negative CT or MRI, angiography should be considered for definitive diagnosis.7

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring is indicated for comatose patients with severe head injury (GCS score <8) postresuscitation and for those with abnormal CT scan findings or with a normal CT but two or more of the following:8

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring Systems

• Intraventricular—catheter is placed in the ventricle, allows for CSF drainage, and is the reference standard for ICP monitoring9

• Intraparenchymal—fiber optic or electronic transducer inserted into the parenchyma

• Subarachnoid bolt—placed in the subarachnoid and uses a fiber optic transducer

• Epidural—uses an optical transducer that rests against the dura

Newer ICP monitoring probes measure cerebral tissue oxygen tension and temperature to better identify and prevent cerebral hypoxia. Figure 36-3 shows ICP monitoring in the emergency department.10

Cerebral Perfusion Pressure

Although ICP monitoring is important in patients with head trauma, an even more crucial number to track is cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). CPP is defined as the mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus ICP. This number indicates the actual pressure of blood perfusing the brain. In head-injured adults, CPP should be maintained at greater than 60 mm Hg at all times.8

Management of Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injuries

Severe head injury is defined as a GCS score of 8 or less after resuscitation. In 2007 the Brain Trauma Foundation, the Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons updated standardized, evidence-based practice guidelines that are applicable to the management of all patients with severe TBI. In 2003 pediatric guidelines were released. These interventions have been shown to minimize the extent and impact of secondary brain injury.11

Breathing

• Maintain PaO2 greater than 100 mm Hg and oxygen saturation greater than 95%.

• Maintain eucapnia (PaCO2 of 35 to 38 mm Hg), as carbon dioxide is a potent vasodilator and will lower CPP.

• Avoid hyperventilation unless signs of herniation are present.

• Initiate exhaled carbon dioxide monitoring.

• Consider neuromuscular blockade for patients who are difficult to ventilate.

Circulation

• Establish normovolemia. Keep MAP at 70 to 90 mm Hg. Hypotension must be avoided, as it is associated with increased mortality in patients with severe brain injury.12

• Maintain CPP greater than 70 mm Hg (an ICP catheter is required to monitor CPP).

• Restore volume as needed with isotonic fluids and blood products.

• Insert an indwelling urinary catheter. Maintain an hourly urine output of 0.5 to 1 mL/kg.

Disability

• Perform and document serial neurologic examinations. The process of secondary injury can develop over a period of hours. Through serial exams, subtle changes in mental status can be observed. Interventions can be instituted to prevent further deterioration.

• Unilateral dilation of pupil is one of the first signs of impending herniation.

Facilitate Diagnosis and Neurosurgical Consultation

• Monitor ICP in all patients with a GCS score of 8 or lower and an abnormal CT scan. Abnormal CT scan refers to the presence of hematomas, contusions, swelling, herniation, or compressed basal cisterns.8

• Facilitate surgical intervention.

• Admit patient to a neurologic critical care unit or transfer to an appropriate facility.

Reduce Intracranial Pressure

• Provide sedation and analgesia.

• Infuse mannitol (an osmotic diuretic), 0.25 to 1 g/kg, in intermittent boluses to patients with signs of impending herniation or decreasing GCS scores not associated with extracranial causes.8

• Maintain the head in a neutral, midline (chin and umbilicus aligned) position.

• Keep the patient’s head elevated 30 degrees, unless contraindicated by a spinal injury. (Most patients will benefit from this position, but some do better when the head rests flat.)

• Remove the cervical collar immediately after the patient has been cleared by a physician. Rigid collars have been shown to increase ICP.13,14

• Minimize external stimulation by keeping lights and noise to a minimum and limiting visitors.9

• Consider administration of pain medication and sedation before suctioning.

• Consider neuromuscular blockade for increased ICP unresponsive to treatment. Patients need particularly close monitoring once this therapy has been initiated

Other interventions that may be performed include the following:

• Hyperventilation as a temporary measure to quickly reduce ICP. Prolonged hyperventilation has been associated with less optimal outcomes.14,15

• Consider ventriculostomy placement for CSF drainage.

• Consider surgical decompression (i.e., hematoma evacuation, lobectomy, craniectomy) for increased ICP unresponsive to medical management.

• Hypertonic saline may be used in the treatment of increased ICP.5

General Care

• Assess for and manage other injuries.

• Perform toxicologic or alcohol screening as indicated. Do not assume that neurologic deficits are alcohol or drug related.15

• Regulate temperature to maintain normothermia. Cooling blankets are necessary, as antipyretics are ineffective because of damage to the neurologic regulation system.9

• Treat seizures. Consider seizure prophylaxis for the first week after injury.

• Do not use intravenous dextrose infusions.

• Do not give dextrose 50%, except in the presence of documented hypoglycemia.

• Consider organ donation in patients with a GCS score of 4 or less who remain unresponsive to treatment.

Specific Head Injuries

Scalp Wounds

Therapeutic Interventions

• Apply direct or peripheral pressure to stop bleeding. Clips or clamps may be used to control major blood loss.

• Palpate the underlying skull for fractures. Do not apply direct pressure over a depressed fracture.

• Immobilize and evaluate the cervical spine.

• Manage hypovolemia. Small children, in particular, are prone to significant volume loss from large scalp wounds.

• Cleanse the wound and debride devitalized tissue.

• Sutures, staples, hair ties, or wound glue may be used to close the scalp.

• Keep wound margins moist with an antibiotic ointment to promote healing.

• Apply a sterile dressing or leave the wound open to air.

• Systemic antibiotics are indicated for contaminated wounds such as bites.

• Ensure appropriate tetanus prophylaxis.

• Provide aftercare instructions for wound management and head trauma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree