INTRODUCTION

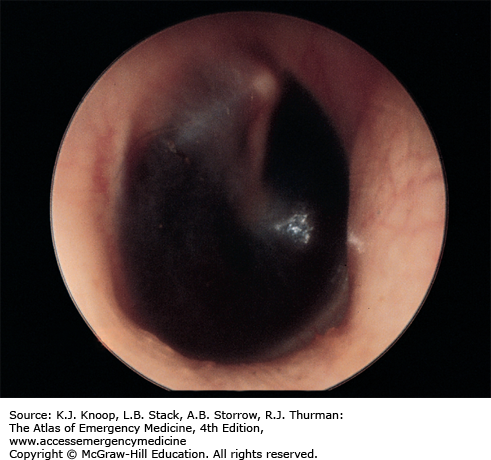

BASILAR SKULL FRACTURE

The skull “base” comprises the frontal bone, occiput, occipital condyles, clivus, carotid canals, petrous portion of the temporal bones, and the posterior sphenoid wall. A basilar skull fracture is basically a linear fracture of the skull base. Trauma resulting in fractures to this area typically does not have localizing symptoms. Indirect signs of the injury may include visible evidence of bleeding from the fracture into surrounding soft tissue, such as a Battle sign or “raccoon eyes.” Bleeding into other structures—including hemotympanum or blood in the sphenoid sinus seen as an air-fluid level on computed tomography (CT)—may also be seen. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks may also be evident and noted as clear or pink rhinorrhea. If CSF is present, a dextrose stick test may be positive. The fluid can be placed on filter paper and a “halo” or double ring may be seen.

Identify underlying brain injury, which is best accomplished by CT. CT is also the best diagnostic tool for identifying the fracture site, but fractures may not always be evident. Evidence of open communication, such as a CSF leak, mandates neurosurgical consultation and admission. Otherwise, the decision for admission is based on the patient’s clinical condition, other associated injuries, and evidence of underlying brain injury as seen on CT. The use of antibiotics in the presence of a CSF leak is controversial because of the possibility of selecting resistant organisms.

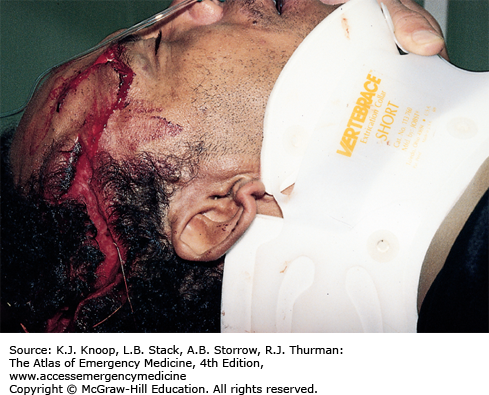

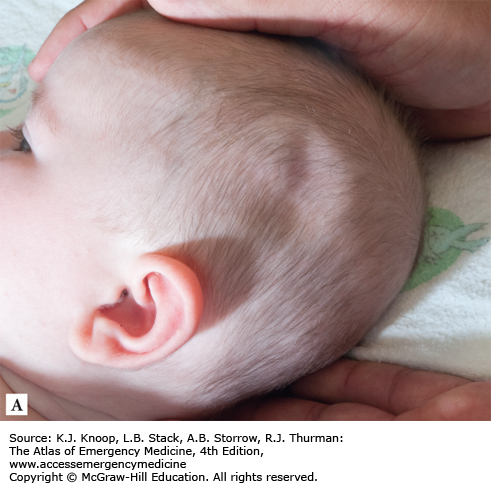

FIGURE 1.1

Battle Sign. Ecchymosis in the postauricular area develops when the fracture line communicates with the mastoid air cells, resulting in blood accumulating in the cutaneous tissue. This patient had sustained injuries several days prior to presentation. (Photo contributor: Frank Birinyi, MD.)

Clinical manifestations of basilar skull fracture may take several hours to fully develop.

There should be a low threshold for head CT in any patient with head trauma, loss of consciousness, change in mental status, severe headache, visual changes, or nausea or vomiting.

The use of filter paper or a dextrose stick test to determine if CSF is present in rhinorrhea is not 100% reliable.

FIGURE 1.7

Halo Sign—Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak. Otorrhea on bed sheet demonstrating a halo sign from a patient with severe head trauma. The distinctive double-ring sign, seen here, comprises blood (inner ring) and CSF (outer ring). The reliability of this test has been questioned. (Photo contributor: Suzanne Bryce, MD.)

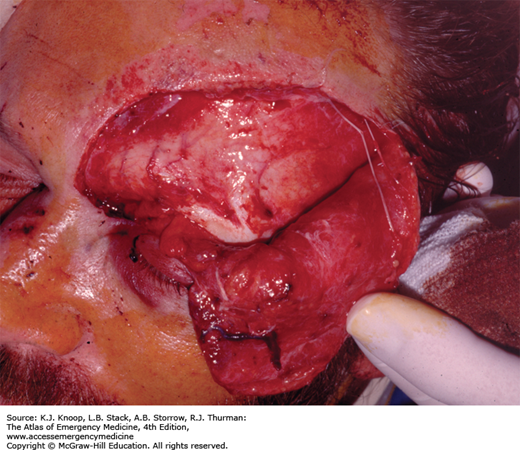

DEPRESSED SKULL FRACTURE

Depressed skull fractures typically occur when a large force is applied over a small area. They are classified as open if the skin above them is lacerated. Abrasions, contusions, and hematomas may also be present over the fracture site. The patient’s mental status is dependent upon the degree of underlying brain injury. Direct trauma can cause abrasions, contusions, hematomas, and lacerations without an underlying depressed skull fracture. Evidence of other injuries such as a basilar fracture, facial fractures, or cervical spinal injuries may also be present.

Explore all scalp lacerations to exclude a depressed fracture. CT should be performed in all suspected depressed skull fractures to determine the extent of underlying brain injury. Depressed skull fractures require immediate neurosurgical consultation. Treat open fractures with antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis as indicated. The decision to observe or operate immediately is made by the neurosurgeon. Children below 2 years of age with skull fractures can develop leptomeningeal cysts, which are extrusion of CSF or brain through dural defects. For this reason, children below age 2 with skull fractures require close follow-up or admission.

Examine all scalp injuries including lacerations for evidence of fractures or depression. When fragments are depressed 5 mm below the inner table, penetration of the dura and injury to the cortex are more likely.

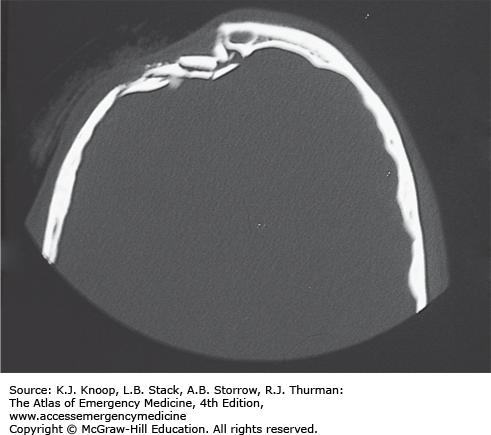

Children with depressed skull fractures are more likely to develop epilepsy.

Ping pong ball skull fractures can occur from a forceps delivery or from compression by mother’s sacral promontory during delivery.

Patients with head injuries must be evaluated for cervical spine injuries.

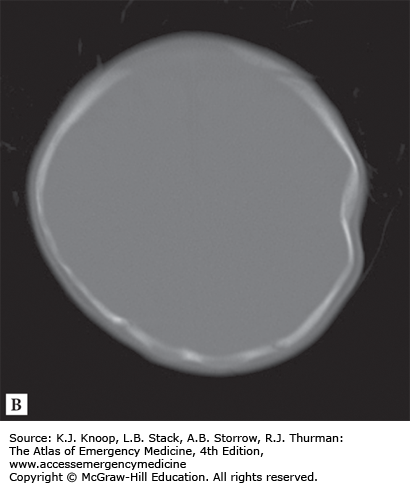

FIGURE 1.10

Ping Pong Ball Skull Fracture. (A) Akin to the greenstick fracture, a ping pong ball fracture occurs when a newborn or infant’s relatively soft skull is indented by the corner of a table or similar object without causing a frank break in the bone. (B) CT demonstrates the ping pong ball effect. (Photo contributor: Johnny Wei, BS.)

NASAL INJURIES

Clinically significant nasal fractures are almost always evident with deformity, swelling, and ecchymosis. Fractures to adjacent bony structures, including the orbit, frontal sinus, or cribriform plate, often occur. Epistaxis may be due to a septal or turbinate laceration but can also be seen with fractures of adjacent bones, including the cribriform plate. Septal hematoma is a rare but important complication that, if untreated, may result in necrosis of the septal cartilage and a resultant “saddle-nose” deformity. A frontonasoethmoid fracture has nasal or frontal crepitus and may have telecanthus or obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct.

Look for more serious injuries first. Patients with associated facial bone deformity or tenderness may require CT to rule out facial fractures. Isolated nasal fractures rarely require radiographs. Refer obvious deformities within 2 to 5 days for reduction, after the swelling has subsided. Nasal fractures with mild angulation and without displacement may be reduced in the emergency department (ED). Nasal injuries without deformity need only conservative therapy with an analgesic and possibly a nasal decongestant. Immediately drain septal hematomas, with packing placed to prevent reaccumulation. Uncontrolled epistaxis may require nasal packing. Vigorously irrigate and suture lacerations overlying a simple nasal fracture and place the patient on antibiotic coverage. Complex nasal lacerations with underlying fractures should be repaired by a facial surgeon.

Control epistaxis to perform a good intranasal examination. If obvious deformity is present, including a new septal deviation or deformity, treat with ice and analgesics and provide ENT referral in 2 to 5 days for reduction.

Although the effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent toxic shock syndrome is unproven, patients discharged with nasal packing should be placed on antistaphylococcal antibiotics and referred to ENT in 2 to 3 days.

Consider cribriform plate fractures in patients with clear rhinorrhea after nasal injury, with the understanding that this finding may be delayed.

Patients with facial trauma should be examined for a septal hematoma.

FIGURE 1.11

Nasal Fracture. Deformity is evident on examination. Note periocular ecchymosis indicating the possibility of other facial fractures (or injuries). The decision to obtain radiographs is based on clinical findings. A radiograph is not indicated for an isolated simple nasal fracture. (Photo contributor: David W. Munter, MD.)

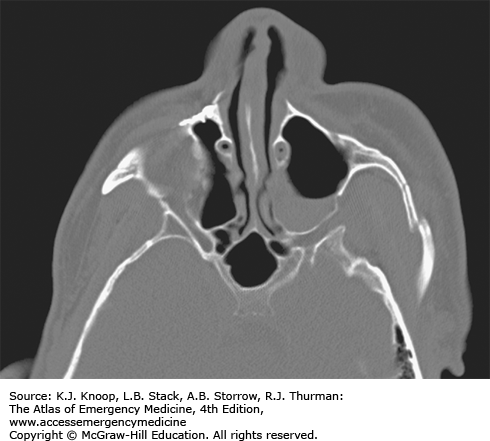

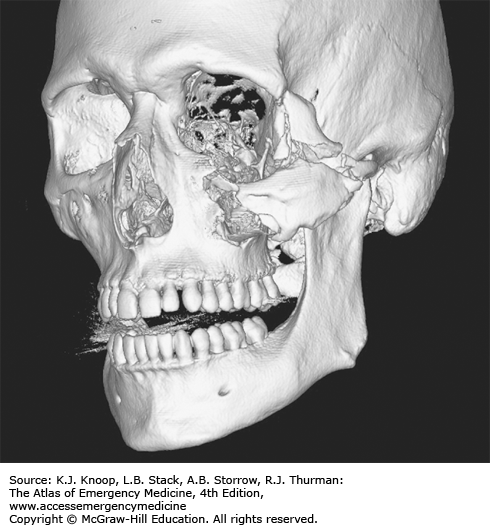

ZYGOMA FRACTURES

The zygoma bone has two major components, the zygomatic arch and the body. The arch forms the inferior and lateral orbit, and the body forms the malar eminence of the face. Direct blows to the arch can result in isolated arch fractures. These present clinically with pain on opening the mouth secondary to the insertion of the temporalis muscle at the arch or impingement on the coronoid process. More extensive trauma can result in the “tripod fracture,” which consists of fractures through three structures: the frontozygomatic suture; the maxillary process of the zygoma including the inferior orbital floor, inferior orbital rim, and lateral wall of the maxillary sinus; and the zygomatic arch. Clinically, patients present with a flattened malar eminence and edema and ecchymosis to the area, with a palpable step-off on examination. Injury to the infraorbital nerve may result in infraorbital paresthesia, and gaze disturbances may result from injury to orbital contents. Subcutaneous emphysema may be present.

Maxillofacial CT best identifies zygoma fractures. Treat simple zygomatic arch or tripod fractures without eye injury with ice and analgesics and refer for delayed operative consideration in 5 to 7 days. Refer extensive tripod fractures or those with eye injuries urgently. Decongestants and broad-spectrum antibiotics are generally recommended for tripod fractures, since the fracture crosses into the maxillary sinus. Fractures with blood in the sinus should also be treated with antibiotics.

Tripod fractures are often associated with orbital and ocular trauma. Palpate the zygomatic arch and orbital rims carefully for a step-off deformity.

Examine for eye findings such as diplopia, hyphema, or retinal detachment. Check for infraorbital paresthesia indicating injury or impingement of the second division of cranial nerve V.

Visual inspection of the malar eminence from several angles (especially by viewing the area from over the head of the patient in the coronal plane) allows detection of a subtle abnormality.