HAND TRAUMA

MICHAEL WITT, MD, MPH AND JINSONG WANG, MD, PhD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Hand trauma is extremely common in the pediatric emergency department, with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations. Injuries include fractures, sprains and soft tissue injuries, nail bed injuries, and lacerations. Understanding the anatomy, injury patterns, and necessary management and referral for ideal recovery of the hands is vital for future function. Further, the provider should recognize that injury to the hands can result from nonaccidental trauma and be vigilant for related findings and concerns.

KEY POINTS

Lacerations and soft tissue injuries are more common in younger children and fractures are seen more frequently in older children.

Lacerations and soft tissue injuries are more common in younger children and fractures are seen more frequently in older children.

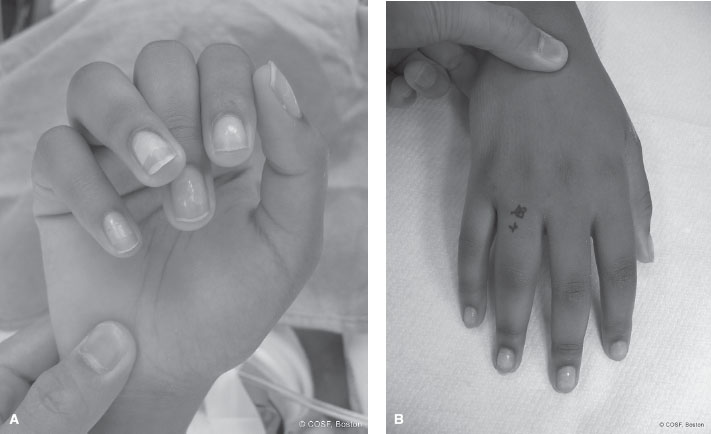

Thorough examination should include a visual examination, general alignment of the hand and digits (Fig. 117.1), focused palpation, passive and active range of motion across each joint (Fig. 117.2), and a neurovascular assessment.

Thorough examination should include a visual examination, general alignment of the hand and digits (Fig. 117.1), focused palpation, passive and active range of motion across each joint (Fig. 117.2), and a neurovascular assessment.

Clinical vigilance is required for possible scaphoid fractures or carpal ligamentous injuries as long-term issues can arise from inadequate care.

Clinical vigilance is required for possible scaphoid fractures or carpal ligamentous injuries as long-term issues can arise from inadequate care.

Skin wounds obtained during an altercation (“fight bites”) represent a risky injury with a high chance of infection due to human oral flora.

Skin wounds obtained during an altercation (“fight bites”) represent a risky injury with a high chance of infection due to human oral flora.

A finger splint is not adequate immobilization for proximal phalanx fractures and a hand- or forearm-based splint is more appropriate.

A finger splint is not adequate immobilization for proximal phalanx fractures and a hand- or forearm-based splint is more appropriate.

Absorbable sutures are equally effective in fingertip wounds and require less intervention on follow-up.

Absorbable sutures are equally effective in fingertip wounds and require less intervention on follow-up.

CARPALS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• The scaphoid is the most commonly fractured carpal bone.

• Ligamentous injuries and dislocations can be subtle but have significant morbidity.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical recognition. The incidence of carpal fractures is relatively low in children, although increasing awareness has led to improved recognition. In infancy, the carpals are completely cartilaginous and are nearly immune to injury. They progressively ossify beginning with the capitate bone. The scaphoid is by far the most common fractured carpal bone, with most fractures occurring in late childhood and adolescence. Falls are the most frequent cause.

Initial assessment. Physical examination requires attention to edema, range of motion, and point tenderness to localize carpal injuries. Snuffbox tenderness is a useful tool for detecting scaphoid fractures. Pain with axial thumb compression can also be a sign of scaphoid injury. Radiographs are obviously limited in infancy and early childhood because of the lack of ossification. As the patient ages and the carpals are progressively ossifying, comparison with the contralateral side may be of benefit. Dedicated scaphoid views or computed tomography may help to identify some fractures not seen on routine hand or wrist films. Nondisplaced scaphoid fractures may not be obvious on initial x-rays but will be visible on repeat imaging performed 2 weeks following the injury.

Management. Most suspected injuries to the carpal bones can be managed urgently with splinting and outpatient follow-up within 1 to 2 weeks. Scaphoid fractures have different patterns depending on the age of the patient. Younger patients have a significant incidence of fractures involving the distal third of the bone, although waist fractures are still the most common. Adolescents and adults tend to fracture at the waist. A unique fracture to young patients is the avulsion of the distal radial aspect of the scaphoid. This injury often is not diagnosed on first presentation and is seen on radiographs 1 to 2 weeks later. In the emergency department, scaphoid fractures should be managed with a thumb spica splint. Most scaphoid fractures are nondisplaced and managed with cast immobilization, though displaced fractures may require surgical reduction and internal fixation to prevent nonunion. In addition, those who present late with evidence of nonunion should be immobilized and referred to a hand specialist for possible surgical repair.

In addition to fractures, suspicion for ligamentous injuries should be high, particularly in late childhood and adolescence. An important radiologic concept is the distance between the scaphoid and lunate bones. In a true scapholunate dissociation, this space is widened, often called the Terry Thompson sign. This can be difficult to detect in children in whom this space is naturally widened, as the carpals are not fully ossified. It is also important to note that dynamic scapholunate instability may not be shown on routine x-ray, and may be only obvious under stressed view. Perilunate dislocation is best identified with the lateral wrist radiograph, with the bone displaced from its typical midaxial location over the radius. Concern for dissociations and dislocations requires urgent attention by a hand specialist.

FIGURE 117.1 Abnormal tenodesis. Clinical photographs depicting abnormal rotation of the ring finger in the setting of a malrotated phalanx fracture. Note the clinical overlap of the ring finger over the long finger and increased gap between the ring finger and the small finger, with passive wrist extension (A) that is not clinically as apparent with the wrist in neutral position and the digits extended (B). (Courtesy of Children’s Orthopaedic Surgery Foundation.)

METACARPALS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Metacarpal fractures can occur at the base, shaft, or neck of the bone, with the neck of the 5th metacarpal being the most common.

• The amount of fracture angulation allowed increases across the metacarpals, from 10 to 20 degrees for the index finger up to 40 degrees for the small finger.

• MCP dislocations can be difficult to identify on radiograph and may simply appear hyperextended.

FIGURE 117.2 Clinical photograph of a patient with an isolated flexor digitorum profundus rupture of the long finger. Note the abnormal digital cascade and resting flexion posture of the long finger in relationship to the adjacent unaffected digits. (Courtesy of Children’s Orthopaedic Surgery Foundation.)

Clinical Considerations

Clinical recognition. Injuries to the metacarpals include fractures and dislocations of the MCP joint. Carpometacarpal joint dislocation is rare in children, although such a dislocation may coexist with another injury. The metacarpals may be fractured at the base, shaft, or neck. These injuries often occur from crushing trauma in younger patients as well as from impact along the axis of the bones, such as in fighting, in older children and adolescents. Compartment syndrome in the hand can occur, particularly with multiple fractures and crush injury, thus careful physical examination and appropriate suspicion are required.

Initial assessment and management. Fractures of the metacarpals are least likely to occur in the base of the bone. When these occur, they usually involve the small finger. There will be significant pain and dorsal edema, which can make accurate diagnosis challenging. Minimally or nondisplaced fractures are generally managed with a splint or cast. Displaced fractures often require closed reduction, possible pinning, and subsequent casting. Carpometacarpal dislocations alone or in conjunction with a base fracture are unstable and often require operative stabilization. Bennett fractures, or intra-articular fracture of the base of the thumb metacarpal, mandate special attention, as the thumb carpometacarpal joint is critical for full use of this digit (Fig. 117.3). Similarly, Rolando fractures, comminuted fractures of the base of the thumb metacarpal, also require careful attention. These fractures can be addressed temporarily with a thumb spica splint and timely referral.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree