Haematology and Oncology

Blood product transfusion is common in critically ill patients. The risks and expense associated with transfusion require that practitioners use products appropriately and can manage complications.

Indications

Packed red cells:

Major haemorrhage (see major haemorrhage protocol, p.115)

p.115)

Correction of symptomatic or severe anaemia

Sickle cell crises (see p.310)

p.310)

FFP, cryoprecipitate, platelets:

Human albumin solution:

Fluid resuscitation (except in cases of TBI)

Plasma exchange

Paracentesis of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome

Compatibility

Compatibility predominantly applies to packed red cells and FFP, and should obey the following rules:

Packed red cells:

Blood group O patients can only receive group O blood

Group A patients can receive group O or A blood

Group B patients can receive group O or B blood

Group AB patients can receive O, A, B, or AB blood

Female patients of child-bearing age must only receive Rhesus D negative blood

Patients with Rhesus D negative blood should preferentially receive Rhesus D negative units, but can receive positive units if necessary

Other red blood cell antigen/antibody reactions should be ruled out by a crossmatch wherever possible

FFP:

Patients should preferentially receive units of the same group as their own blood

All patients can receive A, B, or AB, but it may need checking to ensure it does not contain a high titre of anti-A or anti-B activity

Only group O patients can receive group O FFP.

Blood conservation strategies

Where major haemorrhage (>1000 ml or >20% estimated blood volume) is predicted in a critically ill patient (e.g. a patient with critical illness who has to undergo a major surgical procedure) consider:

Administering antifibrinolytics: tranexamic acid IV (loading dose 1g); protamine is no longer recommended.

Perioperative cell salvage.

Haemoglobin transfusion triggers

A conservative blood transfusion policy should be used within critical care. The transfusion trigger should be

Ongoing bleeding/early septic shock: 8-10 g/dl

Known ischaemic heart disease: 10 g/dl

Symptomatic anaemia (e.g. dyspnoeic): 9-10 g/dl

All other cases: 7-9 g/dl

It is also suggested that patients with burns, cerebrovascular disease or head injury should share a transfusion trigger of 8-10 g/dl

Safety requirements

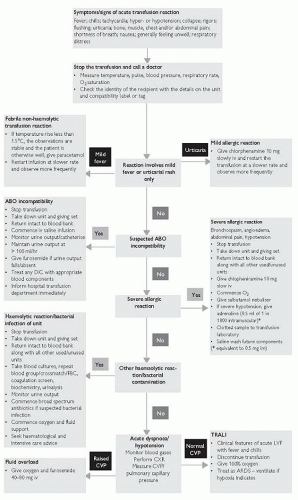

Transfusion of blood products requires a ‘zero-tolerance’ approach to sampling, prescribing, and administration (Fig. 9.1), and should include:

Crossmatch samples should be taken from one patient at a time:

Patients should be identified by full name, date of birth and hospital/NHS number (by wrist band and verbally if possible)

Sample tubes should be hand-written at the bedside

All products should be prescribed using a record which contains full patient identification as just described.

Administration of blood products should only occur after a 2-person check of blood products, prescription and patient identification:

Any errors should prompt the administration to be abandoned

Details of the transfusion, including start/finish times and serial numbers should be recorded

There is a legal requirement to keep a traceable record of all blood products transfused in Europe.

Special measures

This refers to the need for irradiated or CMV negative blood products. In the following cases transfusion should be discussed with a haematologist in case special measures are required:

Patient refusal

Adult patients, in particular Jehovah’s Witness patients, have an absolute right to refuse blood product transfusions. This may differ from patient to patient and some techniques, such as cell salvage, may be acceptable to some. This should be discussed in detail with them.

Complications

Acute transfusion reaction:

Hypotension, fever, or allergic reactions occurring within 24 hours of a transfusion

Error in transfusion requirements or administration; inappropriate/unnecessary transfusion:

Failure to adhere to ‘cold chain’, or excessive administration time (>3.5 hours)

Use of expired red cells

Failure to administer anti-D

Failure to apply special measures (irradiated/CMV negative products)

Over-transfusion as a result of blood sample laboratory errors or over-enthusiastic transfusion prescribing

Haemolytic transfusion reaction:

Most commonly occurs if ABO incompatible blood transfused, but can involve uncommon antibodies, or bacterial overgrowth

Associated with fever/rigors, chest, back or abdominal pain, sweating, tachycardia and hypotension, tachypnoea and cyanosis, oliguria, haemoglobinuria, DIC

Can be acute or delayed in onset

More common in patients with sickle cell disease

Transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO):

Within 6 hours of a transfusion, any 4 of: tachypnoea/dyspnoea, tachycardia, hypertension, pulmonary oedema, peripheral oedema

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI):

Transfusion associated dyspnoea (TAD):

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease:

Fever, rash, liver dysfunction, diarrhoea, pancytopaenia and marrow hypoplasia <30 days after transfusion

Transfusion transmitted infection:

Fever, sepsis or infection associated with the transmission of infections such as: bacteria, malaria, HIV, hepatitis viruses, or new-variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Post-transfusion purpura:

Thrombocytopaenia 5-12 days after red cell transfusion

Further reading

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Management of anaesthesia for Jehovah’s Witnesses. London: AAGBI, 1999.

Hebert PC, e al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care (TRICC). N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 409-17.

McClelland DBL, et al. Handbook of transfusion medicine, 4th edn. London: United Kingdom Blood Services, 2007.

SAFE study Investigators. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2247-56.

SAFE study Investigators. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 874-84.

Abnormally delayed blood clotting may occur due to deficiencies in amount and/or function of coagulation factors and platelets. Clinically, this may lead to problems with bleeding, purpura, and bruising. In the critically ill, deranged haemostasis is often multifactorial.

Causes

Acquired coagulation factor deficiency

Dilution 2° to massive transfusion.

Liver failure.

Consumption (e.g. DIC, extracorporeal circulation).

Drugs (e.g. heparin, warfarin).

Nutritional deficiency, particularly vitamin K.

Autoantibodies (e.g. lupus anticoagulant, anti-Factor VIII antibody).

Primary fibrinolysis (e.g. burns, neurosurgery, malignancy).

Amyloid (Factor X deficiency).

Inherited coagulation factor deficiency

Haemophilia A (Factor VIII deficiency) and B (Factor IX deficiency, Christmas disease).

von Willebrand’s disease (Factor VIII deficiency/platelet dysfunction).

Thrombocytopaenia, caused by reduced platelet production

Marrow infiltration by malignancy.

Marrow failure (e.g. critical illness, sepsis, viruses).

Nutritional deficiency (e.g. vitamin B12, folate).

Drugs (e.g. cytotoxics, alcohol).

Platelet dysfunction

Drugs (e.g. aspirin, NSAIDs, clopidogrel, abciximab).

Uraemia.

Liver failure.

Leukaemias.

Inherited platelet disorders (rare), e.g. Glanzmann’s disease, Bernard-Soulier syndrome.

Presentation and assessment

Haemorrhage, including intraoperative failure to achieve haemostasis.

Oozing from wounds and drain sites.

Spontaneous bleeding, bruising, or purpura (atypical sites such as muscles and joints may be involved).

Incidental finding on haematological investigation.

Investigations

Basic investigations should include:

Involvement of a haematologist is required in many cases as more specialized haematological tests may be indicated, for example:

Blood film and/or bone marrow aspirate.

Antiplatelet antibody tests/autoantibody screen.

Platelet function tests.

Specific coagulation factor levels.

FDPs, D-dimers.

Differential diagnoses

Meningococcal, streptococcal septicaemia; infective embolic rashes.

Ongoing bleeding.

Over anticoagulation.

Lab error, or sample contamination (i.e. from IV drip arm).

Immediate management

Give O2 as required, support airway, breathing, and circulation.

If the patient is clinically shocked, begin fluid resuscitation, following a major haemorrhage protocol if appropriate (see p.115)

p.115)

Maintain a high index of suspicion for ‘surgical’ or other bleeding and stop local bleeding where possible:

In postoperative patients or following trauma

Following invasive procedures and line insertion

In patients at risk of GI bleeding

Send urgent blood for crossmatch, FBC and coagulation screen

Avoid hypothermia and acidosis (both impair coagulation)

Avoid/stop NSAIDS, anticoagulants; avoid IM injections

In cases of major trauma or major haemorrhage 1 g IV tranexamic acid may decrease the amount of blood loss due to fibrinolysis.

Coagulopathy

10-15 ml/kg1 FFP, will rapidly reverse of clotting factor deficiency: aim for an INR <1.5 in the bleeding patient

If fibrinogen is low (<1.0 g/L), often associated with massive transfusion and DIC, give cryoprecipitate

Warfarin overdose (only needs rapid correction if there is bleeding/risk of bleeding):

Heparin overdose (often rapidly excreted if renal function normal), if the heparin infusion is stopped APTT should normalize in 2-4 hours

Can be corrected with IV protamine (slowly over 10 minutes): 1 mg/100 units of heparin

Thrombocytopaenia

In cases of haemorrhage, DIC, massive transfusion, or where surgical Intervention is required aim for a platelet count >50 × 109/L

In cases of major trauma or requiring CNS surgery aim for a platelet count >100 × 109/L

In chronic thrombocytopaenia without bleeding aim for a platelet count >10 × 109/L

1 adult dose2 will raise the platelet count by ˜10 × 109/L

‘Antiplatelet’ drugs should be stopped; irreversible drugs such as clopidogrel or aspirin mean that transfusion may be necessary despite apparently normal platelet numbers

Further management

Ongoing transfusion necessitates regular coagulation studies and platelet counts, as does critical illness.

Ongoing bleeding in the face of normal coagulation studies and platelet numbers should prompt a thorough search for a surgical cause.

Avoid hypothermia, acidosis, and correct hypocalcaemia (calcium is an important cofactor in the coagulation cascade).

Thrombocytopaenia/platelet dysfunction:

Involvement of a haematologist is indicated if no cause is apparent as bone marrow biopsy or specialist tests to diagnose and quantify abnormal platelet function may be required

Immune thrombocytopaenia (ITP) is treated with IV immunoglobulin and steroids; platelets are rarely indicated

Thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura/haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS/TTP) requires specialist haematology/renal input; platelet transfusions may result in further thromboses

Dialysis and desmopressin can be used in the setting of platelet dysfunction 2° to uraemia

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Irreversible ‘antiplatelet’ drugs, particularly aspirin and clopidogrel, should be stopped 5-10 days before surgery and invasive procedures.

FFP and cryoprecipitate take up to 30 minutes to thaw.

Platelets are held centrally and may time to reach peripheral hospitals.

Be careful with NGT or urinary catheter insertion in the coagulopathic.

In coagulopathic patients minor trauma can cause catastrophic bleeds.

Further reading

Balikai G, et al. Haemotological problems in intensivse care. Anaesthes Intensive Care Med 2009; 10(4): 176-8.

DeLoughery TG. Thrombocytopaenia in critical care patients. J Intensive Care Med 2002; 17(6): 267-82.

George JN. Evaluation and management of pateints with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Intens Care Med 2007; 22(82): 82-91.

Keeling D et al. The management of heparin induced thrombocytopaenia. Br J Haematol 2006; 133: 259-69.

Clotting function tests

Prothrombin time (PT; normal 12-14 seconds):

Assesses factor VII activity (extrinsic coagulation pathway)

Prolonged in liver disease, warfarin, vitamin K deficiency

Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT; normal 25-35 seconds):

Assesses factors VIII, IX, XI, XII (intrinsic coagulation pathway)

Normal PT and prolonged APTT suggests heparin use, or inherited defect (von Willebrand’s disease, antiphospholipid syndrome, haemophilia)

Thrombin time (TT; normal 10-12 seconds):

Assesses thrombin and fibrinogen (common clotting pathway)

Prolonged with heparin, fibrinogen defect, FDPs

Platelet count (thrombocytopaenia is a count <150 × 109/L):

Does not assess platelet function

Fibrinogen (normal 2-4g/L):

Reduced in DIC and severe liver disease

Fibrin degradation products (FDPs, normal 10mg/L) and D-dimers:

Heparin-induced thrombocytopaenia (HIT)

Thrombocytopaenia in patients exposed to heparins may be caused by HIT, an antibody-mediated disease that reduces platelet survival and can trigger thromboses. Scoring systems help assess the probability:

Thrombocytopaenia:

2 points: fall in platelet count of >50%, or nadir 20-100 × 109/L

1 point: fall in platelet count of 30-50%, or nadir 10-19 × 109/L

0 points: fall in platelet count of <30%, or nadir <10 × 109/L

Timing (heparin exposure = day 0):

2 points: onset day 5-10 (or day 0 if heparin within past 100 days)

1 point: onset >day 10, or dates unclear

0 points: onset day 1-4

Thrombotic events or skin lesions:

2 points: new thrombus or skin necrosis

1 point: progressive/recurrent or suspected thrombus

0 points: no events

Other potential causes:

2 points: no other cause

1 point: other possible causes

0 points: other definite cause

Score 0-3: low risk; 4-5 intermediate risk; 6-8 high risk. If HIT is likely:

Stop all heparin/LMWH.

Perform ELISA antigen assays (or serotonin release assay).

Anticoagulate with danaparoid or lepirudin (avoid warfarin).

Platelet transfusions are rarely necessary.

DIC is a ‘consumptive’ coagulopathy characterized by abnormal, widespread intravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis leading to loss of coagulation factors and platelets. Bleeding and microvascular thrombosis causing organ damage can occur.

Causes

There are many causes of DIC, including:

Sepsis (60% of cases).

Trauma (especially crush injury and tissue necrosis), and burns.

Obstetric emergencies: severe pre-eclampsia, abruption, amniotic fluid embolism/anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy, IUFD.

Anaphylaxis.

Transfusion reactions and haemolysis.

Malignancy: e.g. mucinous adenocarcinomas, promyelocytic leukaemia.

Pancreatitis and/or liver failure.

Heat stroke.

DKA.

Autoimmune disease.

Toxins: snake bites, recreational drugs.

Presentation and assessment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

p.115

p.115 p.302

p.302

p.306

p.306 p.305

p.305