GENITOURINARY TRAUMA

GREGORY E. TASIAN, MD, MSc, MSCE AND ROBERT A. BELFER, MD

Genitourinary trauma in children is common with approximately 28,000 children presenting to emergency departments in the United States annually with genitourinary injuries. Approximately 10% of patients with serious multisystem trauma have genitourinary injuries. Most injuries (90%) are the result of blunt trauma that involves crush injuries and acceleration/deceleration forces related to motor vehicle collisions, falls of high-velocity injuries such as sledding, skateboarding, or skiing.

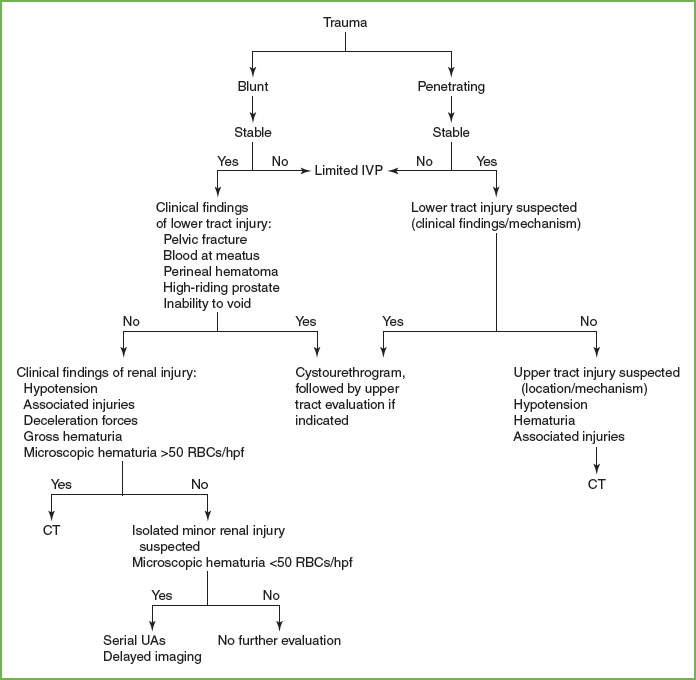

The clinical approach to the injured child should strictly follow advanced trauma life support guidelines. Figure 116.1 provides an algorithm for diagnostic evaluation of pediatric patients with genitourinary trauma. Urologic management may be temporized to permit urinary drainage in the initial phases; the patient may subsequently require operative procedures.

KEY POINTS

The goal of emergency therapy for genitourinary injury is to maximize organ preservation and minimize future morbidity.

The goal of emergency therapy for genitourinary injury is to maximize organ preservation and minimize future morbidity.

Assessment of the genitourinary system can be undertaken once life-threatening conditions have been identified and the child has been resuscitated.

Assessment of the genitourinary system can be undertaken once life-threatening conditions have been identified and the child has been resuscitated.

Management of hemodynamically stable children with renal injuries should proceed on the basis of radiographic staging of the traumatic injury.

Management of hemodynamically stable children with renal injuries should proceed on the basis of radiographic staging of the traumatic injury.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Resuscitation and Stabilization

• Approach to the Injured Child: Chapter 2

Signs and Symptoms

• Vaginal Discharge: Chapter 76

• Vaginal Bleeding: Chapter 75

Medical, Surgical and Trauma Emergencies

GOALS OF EMERGENCY THERAPY

The goal of emergency therapy for genitourinary injury is to maximize organ preservation and minimize future morbidity.

To achieve these goals, the initial management of children with genitourinary injury in the emergency department centers on prompt recognition and staging of injuries, followed by appropriate urologic consultation for management and potential surgical intervention for these injuries. The recognition and treatment of children with genitourinary injury requires an understanding of the clinical situations and signs and symptoms associated with genitourinary injury and appropriate use of diagnostic imaging. To provide a comprehensive and accessible guide for management of children with genitourinary injury, we discuss trauma of each genitourinary organ separately yet emphasize the potential for concomitant extrarenal injury and need for maintaining a high level of suspicion for these associated injuries.

KIDNEY

Goal of Treatment

The principle underlying the management of pediatric renal trauma is preservation of renal tissue and function minimizing morbidity and mortality. Patients who are hemodynamically unstable or have sustained severe intra-abdominal penetrating trauma require immediate surgical intervention. Management of hemodynamically stable children should proceed on the basis of radiographic staging of the traumatic injury.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

In the adult population, radiographic evaluation is required in patients with hypotension, penetrating injuries in the vicinity of urologic organs, associated abdominal injuries, or the presence of any degree of hematuria. Criteria regarding the imaging of children with penetrating trauma are less well established.

Hypotension is not a reliable indicator of significant renal injury in children and therefore should not be used to guide management; however, most patients with multisystem trauma and hypotension undergo an abdominal computed tomographic (CT) scan screening for nonurologic injuries. Radiographic evaluation of the pediatric genitourinary tract is necessary in cases with clinical signs indicative of renal injury, gross hematuria, major associated injuries, or history of significant deceleration forces. For blunt abdominal trauma, imaging should be performed in any stable child with gross hematuria or significant microscopic hematuria (>50 red blood cells per high power field) associated with shock (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg). However, the late manifestations of shock in children with traumatic injuries have led some experts to recommend imaging in any stable child with microscopic hematuria >50 red blood cells with or without shock. Additionally, any child with a significant associated injury or a suspicious mechanism of injury such as a rapid deceleration, high velocity strike, fall from >15 ft, or a direct blow to the abdomen or flank should be imaged regardless of the presence of hematuria. All clinically stable children with penetrating abdominal or pelvic trauma should undergo radiographic assessment. Stable blunt trauma patients with microscopic hematuria may be observed without imaging, unless they suffered a major acceleration or deceleration injury such as a fall from a great height or high speed MVC.

FIGURE 116.1 Algorithm for the evaluation of the pediatric patient with genitourinary trauma. IVP, intravenous pyelogram; CT, computed tomography; RBC, red blood cell; HPF, high-powered field; UAs, urinalyses.

Current Evidence

Approximately half of all genitourinary injuries involve the kidney. Children are more likely than adults to sustain renal injuries for the following reasons: The pediatric kidney is larger in proportion to the size of the abdomen than in adults; the child’s kidney may retain fetal lobations which allow for easier parenchymal disruption; the pediatric kidney has inadequate protection due to weaker abdominal musculature, a less well-ossified thoracic cage, and less developed perirenal fat and fascia than in adults. Most pediatric renal trauma is minor, requiring no intervention.

Blunt trauma accounts for more than 90% of renal injuries in children. Most pediatric renal trauma is sustained in motor vehicle accidents. Falls, sports-related incidents, and direct blows are also common mechanisms of injury. In these scenarios, the kidneys are crushed against the ribs or vertebral column from their relatively fixed position within Gerota fascia. Contusions or renal lacerations can occur. In addition, the vascular pedicle can be stretched causing renal vein or artery injuries. Penetrating trauma accounts for the remaining cases. Approximately 10% of penetrating abdominal injuries involve the kidney.

Minor renal injuries account for 85% of total injuries, lacerations in 10% and severe kidney ruptures, fractures of pedicle injuries in less than 5% of cases.

Associated extrarenal injuries often occur, with head injuries being the most common. Associated intraperitoneal injuries occur in 80% of patients with penetrating renal trauma and 20% of patients with blunt renal trauma. In general, the hospital length of stay is determined by the associated injuries and not the renal injuries.

Coincidental congenital renal anomalies and intrarenal tumors have been reported in up to 20% of children with renal injuries. More accurate recent reviews show that the incidence rate is closer to 1%. Historically, pre-existing anomalies have been believed to increase the risk and severity of injury to the kidney. However, it appears that in most patients, congenital genitourinary anomalies associated with renal injury are incidental findings and do not increase morbidity. Nevertheless, a high index of suspicion should be maintained in any child who presents with gross hematuria after a relatively minor trauma. Other patients may present with an acute abdomen due to intraperitoneal rupture of a hydronephrotic kidney.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Children who sustain significant renal injuries usually present with localized signs such as flank tenderness, hematoma, palpable mass, or ecchymosis. However, since kidney injuries are often associated with injuries to other organs, generalized abdominal tenderness, rigidity of the abdominal wall, paralytic ileus, and hypovolemic shock may all be part of the clinical picture. Penetrating injuries to the chest, abdomen, flank, and lumbar regions should alert the clinician to the possibility of a renal injury.

Hematuria has long been considered the cardinal marker of renal injury. However, the degree of hematuria does not correlate with the severity of the renal lesion. Additionally, hematuria may be absent in up to 50% of patients with vascular pedicle injuries and in approximately one-third of patients with penetrating injuries.

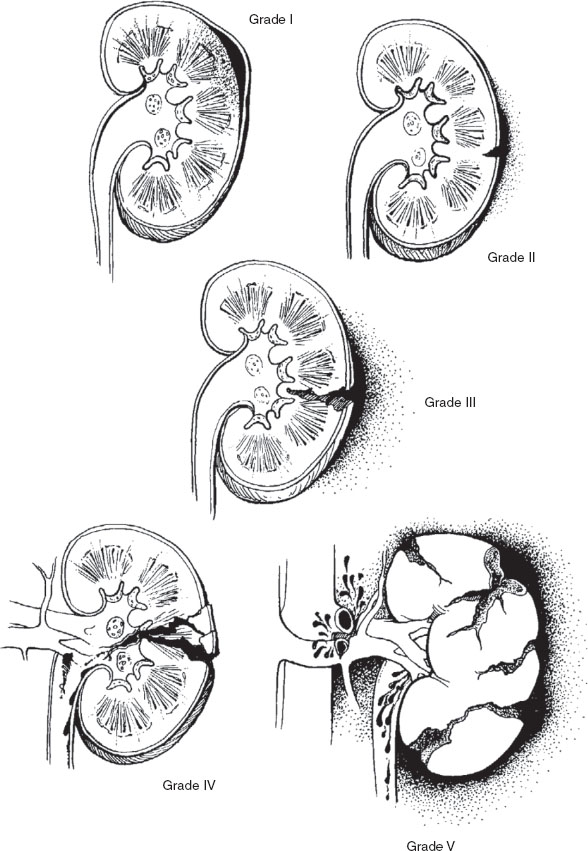

Renal injuries have been described using different classification systems based on the clinical and radiologic assessment of the patient. In 1989, the Organ Injury Scaling Committee of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma developed an injury severity score for classification of renal trauma. This classification system is illustrated in Figure 116.2. Grade I injuries include contusions or subcapsular, nonexpanding hematomas and comprise 80% of all injuries to the kidney. Grade II injuries include nonexpanding hematomas confined to the retroperitoneum or lacerations less than 1 cm in depth without urinary extravasation. Grade III injuries include lacerations extending more than 1 cm into the renal cortex without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation. Grade IV injuries include lacerations extending into the collecting system or renal vascular injuries with contained hemorrhage. Grade V injuries include completely shattered kidneys or avulsions of renal hilum with devascularized kidneys.

FIGURE 116.2 Classification of renal injuries as proposed by the Organ Injury Scaling Committee of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Parenchymal contusions and hematomas are the most common renal injuries, accounting for 60% to 90% of all lesions from blunt trauma. Lacerations account for up to 10% of renal injuries and may involve disruption of the capsule, collecting system, or both.

Severe injuries, such as shattered kidney or pedicle avulsions, constitute approximately 3% of renal injuries. Pedicle injuries result from sheer force of the kidney with subsequent stretching of the renal vessels.

Initial Assessment

All injured children should undergo a thorough evaluation based on well-established pediatric trauma protocols. Assessment of the genitourinary system can be undertaken once life-threatening conditions have been identified and the child has been resuscitated. The flank should be inspected for ecchymosis and flank pain, and the presence of a “seat belt sign” should be noted on the abdomen, since all of these physical findings indicate significant trauma and possible renal injury. A urinalysis should be obtained in all patients with multisystem trauma or suspected isolated renal injury.

Management/Diagnostic Testing

Hemodynamically stable patients who present with suggestive clinical findings, gross hematuria, microscopic hematuria of more than 50 RBCs per hpf, major associated injuries, or a history of significant deceleration injury should undergo radiographic evaluation. These patients should have a contrast-enhanced CT scan with delayed images. Children who remain unstable despite resuscitative measures should undergo a one-shot IVP before emergency laparotomy. Children with isolated microscopic hematuria of less than 50 RBCs per hpf do not require immediate imaging. These patients may be discharged and can be evaluated on an outpatient basis with CT, IVP, or ultrasound if hematuria persists. However, in some pediatric trauma centers, management of these patients involves hospitalization for observation, followed by nonemergent radiographic evaluation.

The diagnostic performance of imaging modalities as they relate to the evaluation of renal trauma is reviewed here.

CT

Contrast-enhanced CT with additional 10-minute delayed scan is the “gold standard” imaging modality for staging a stable trauma patient. Trauma patients lacking radiographic signs of renal injury who do not have any perinephric, periureteral, or pelvic fluid collections do not require delayed imaging per expert consensus. If any of these subtle findings, especially low density fluid tracking around the kidney and down the ureter, are present on the initial contrast-enhanced CT. A UPJ or a ureteral injury can easily be missed if delayed images are not obtained.

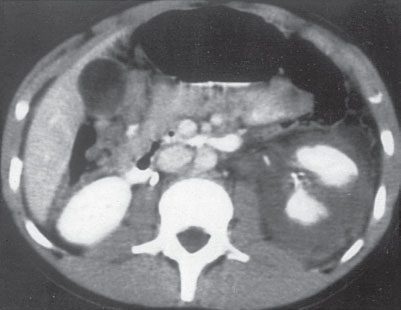

FIGURE 116.3 Renal fracture. Computed tomography section of the abdomen shows fracture of the left kidney with moderate subcapsular hematoma.

The diagnostic accuracy of CT scan has been reported tobe as high as 98% (Fig. 116.3).

The ability of CT to quickly evaluate solid organ and vascular injuries has significantly improved the management of trauma. Important radiologic findings that should be noted when reviewing CT for renal trauma include arterial medial extravasation of contrast, denoting a severe arterial injury; medial hematoma without arterial extravasation, often secondary to a venous injury; differential contrast uptake and excretion, which is indicative of arterial injury or thrombosis; cortical rim sign, often indicative of a main renal artery injury; degree of parenchymal laceration and involvement of the collecting system; degree of devitalized tissue; and the size and location of a perinephric hematoma or fluid collection. Medial extravasation of contrast is often seen with UPJ ruptures and no contrast will be seen in the distal ureter on delayed images of complete UPJ avulsion. Historically diagnosis of UPJ injuries was delayed in 50% of cases but routine evaluation of trauma with CT, especially when delayed images are obtained, has increased the initial detection rate to almost 90%.

Ultrasound

The focused assessment by sonography for trauma (FAST) is often used to evaluate trauma patients for abdominal injuries and intra-abdominal fluid collections. Despite the availability and low risk nature of sonography, this modality has a low sensitivity (48%) for detecting renal injuries and often overlooks significant damages. The use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound has recently been reported to increase the sensitivity to 69%, which is still inferior to the >90% sensitivity of CT.

Intravenous Urography

Although almost completely replaced by CT for evaluating stable trauma patients, the intravenous urogram still maintains a role in evaluating the unstable trauma patient taken directly to the operating room by verifying the presence of a contralateral kidney (1 shot urogram with 2 mL per kg body weight bolus followed by plain film 10 minutes later). Identifying a functional contralateral kidney is important first because every possible attempt should be made to save the injured kidney if it is the only one. The injured kidney may lack contrast uptake if there is a major vascular injury or demonstrate a delayed nephrogram from significant compression from a contained hematoma. An abnormal renal outline, displacement of the bowel or ureter and loss of the psoas margin are all suggestive of renal injury and hematoma. Distinctive patterns of contrast extravasation that should raise concern of a possible UPJ injury include extravasation medial or circumferential (circumferential urinoma) to the kidney. Also, with a complete UPJ disruption, the ipsilateral ureter will lack intraluminal contrast.

Angiography

Angiography has been largely replaced by noninvasive modalities, especially in the pediatric patients in whom technical problems with vascular access result in a higher complication rate than in adults. Arteriography does not add useful information to contrast CT scanning and may increase diagnostic delay during the preoperative workup. It is useful in patients who require therapeutic embolization of an active bleeding site.

Currently, there is no role for radionuclide imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the acute setting for children with suspected renal trauma although there is a role in the follow-up evaluation of renal injury.

Clinical Indications for Discharge or Admission

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree