Genitourinary Trauma

Carrie D. Tibbles

The genitourinary (GU) system is involved in approximately 10% of acutely injured patients (1). The presentation of GU trauma may be occult and is often overshadowed by more dramatic and immediate life-threatening injuries. However, if these injuries are not identified and properly treated, the patient may experience delayed complications and significant long-term morbidity. Clues to suggest the possibility of GU trauma lie in the mechanism of injury, a constellation of associated injuries, and physical examination findings identified during the secondary survey. For diagnosis and management, GU trauma is generally divided into upper tract injuries (kidney and ureter) and lower tract injuries (bladder, urethra, and external genitalia). A systematic approach and thorough understanding of the appropriate diagnostic modalities are necessary for emergency physicians to effectively manage these injuries.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Upper Tract Injury

The kidneys and ureters lie securely in the retroperitoneum, beneath the lower ribs and musculature of the back. Therefore, injuries to the upper urinary tract typically occur in the setting of high-energy, multisystem trauma. Blunt force to the back, flank, or abdomen; falls from height; or, less commonly, rapid deceleration may result in injuries to the kidneys or ureters (2). Upper tract injuries may occur in isolation. However, more commonly, trauma that results in renal injuries produces associated bony, vascular, and visceral injuries that directly contribute to the observed morbidity and mortality (1). Penetrating injury, which accounts for 6% to 11% of renal injuries, is suggested by transaxial wounds or wounds in anatomic proximity to the kidneys and ureter. Although nearly all significant blunt renal injuries will present with either gross or microscopic hematuria, about 25% to 30% of ureteral injuries will not have associated hematuria. The presence of hematuria is a less reliable indicator of upper tract injury with penetrating trauma and the location of the wound is used to guide subsequent management decisions (3). A vascular pedicle injury may present as refractory hypotension following severe blunt trauma; this injury usually results from a deceleration mechanism.

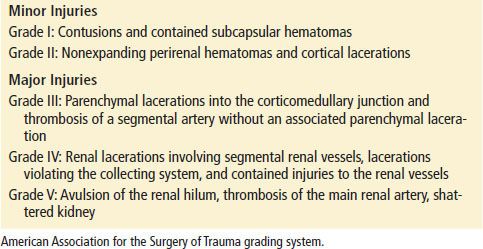

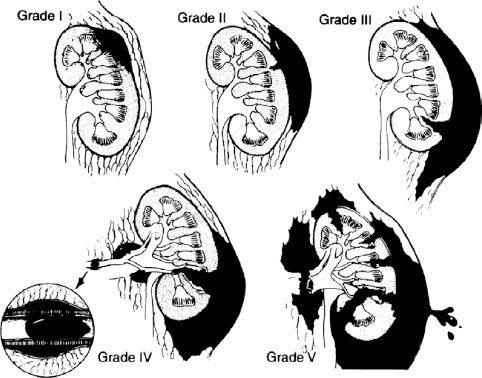

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) has established a classification system for renal injuries based on anatomic location and severity (Table 35.1; Fig. 35.1) (4). Grade I and grade II injuries consist of contusions and lacerations confined to the cortex respectively and are considered minor injuries. Eighty-five percent of renal injuries are classified as minor injuries. Grade III injuries are deeper lacerations that extend into the corticomedullary junction. Lacerations into the collecting system or those involving segmental arteries are grade IV injuries. The most severe injuries are classified as grade V and include a shattered kidney, thrombosis of the main renal artery, or avulsion of the renal hilum. A review of the National Trauma Data Bank found that the AAST injury scale predicts the need for nephrectomy in both blunt and penetrating trauma and mortality in blunt trauma patients (5). Recently investigators from Parkland recommended a substratification of grade IV injuries into high risk and low risk based on three predictors of needing operative intervention, specifically, intravascular contrast extravasation, hematoma size greater than 3.5 cm, and a medial renal laceration site (6,7).

TABLE 35.1

Grading System for Renal Injuries

FIGURE 35.1 Grading system of renal injuries. (From Santucci RA, McAninch JW, Safir M, et al. Validation of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma organ injury severity scale for the kidney. J Trauma. 2001;50:195–200, with permission.)

Lower Tract Injuries

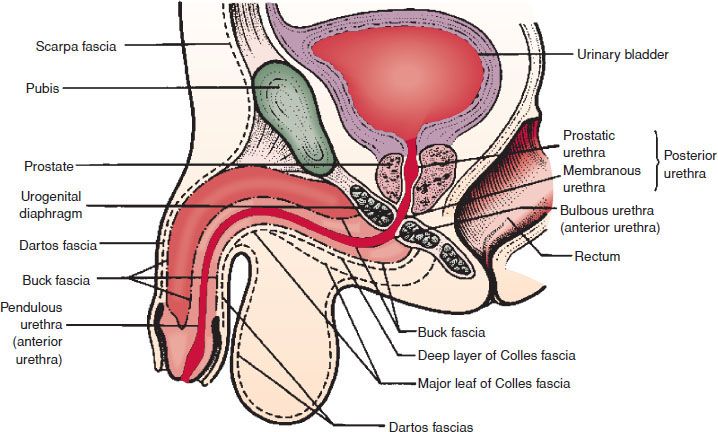

Blunt trauma to the lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra) is usually associated with pelvic rami fractures and symphyseal diastasis. Anterior urethral injuries (penile and bulbous urethra, below the urogenital diaphragm) are associated with self-instrumentation, falls, and straddle injuries. Posterior urethral injuries (membranous and prostatic urethra, above the urogenital diaphragm) commonly accompany pelvic fractures (Fig. 35.2). As the urinary continence mechanism and autonomic innervation responsible for erection are contained in the posterior urethra, posterior urethral injuries may result in permanent incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Signs of anterior urethral injury depend on the integrity of Buck fascia. If this fascial layer is torn, blood and urine may pass into the penis, scrotum, and abdominal wall. Clinical signs of urethral injury are blood at the urethral meatus, high-riding prostate, scrotal or perineal hematoma, and difficulty voiding. However, these signs can be absent in some patients with urethral injury.

FIGURE 35.2 Normal anatomy of the male urethra. (From Schneider RE. Genitourinary system. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002:438, with permission.)

Bladder rupture is classified as extraperitoneal or intraperitoneal. Extraperitoneal bladder injuries are most commonly associated with pelvic fractures and bladder laceration by bony fragments. There is leakage of urine into the perivesicular space. Intraperitoneal bladder injuries result from compressive forces in the presence of a full bladder, and rupture occurs at the dome of the bladder through the peritoneum into the abdominal cavity. The presence of a pelvic fracture and gross hematuria is virtually diagnostic of bladder rupture. Bladder injury is more likely in pelvic fractures with a widened pubic symphysis and sacroiliac disruption (8). Ninety-eight percent of patients with bladder rupture will have gross hematuria. Other signs of bladder injury are suprapubic or lower abdominal pain and tenderness, inability to void, and blood at the urethral meatus.

As with penetrating trauma to the upper GU tract, penetrating injuries to the lower tract are suggested by location of wounds. Any penetration of the lower abdominal wall in the region of the pelvis raises the possibility of urinary tract injury. Given the variability of the projectile tract, any gunshot wound in the region should include consideration of GU tract injury.

External Genitalia Trauma

Testicular injuries are often the result of a fall or direct trauma. They include lacerations, contusions, dislocations, or fractures. Symptoms include pain, nausea, lightheadedness, and acute urinary retention. A swollen, tender testicle or a hematoma may be seen on physical examination. Penile injuries range from small lacerations and contusions to complete amputations. Penile fracture, which involves rupture of the tunica albuginea, most commonly occurs during overzealous vaginal intercourse, although several other mechanisms have been reported (9). Any constricting object placed around the penis can result in marked edema and eventual incarceration and necrosis distal to the constriction. Entrapment of the penis in a zipper occurs most often in uncircumcised young boys.

Vaginal injuries are frequently complications of pelvic fractures but may also be seen following sexual assault or other penetrating injuries. The majority of patients present with vaginal bleeding. A careful vaginal examination is required in any female patient suspected of having a pelvic fracture. According to one series, up to one-third of patients with vaginal trauma unrelated to childbirth will have concurrent urethral injuries (10).

ED EVALUATION

Upper Tract Injury

The emergency department (ED) evaluation of a multitrauma patient begins with the standard advanced trauma life support assessment and resuscitation. In this manner, immediately life-threatening injuries are identified and treated. In the unstable patient requiring emergency laparotomy for other reasons, gross hematuria and signs of a pelvic fracture should be noted during the secondary survey. Definitive evaluation of the GU tract can be performed once the patient has been stabilized. In the stable patient, the emergency physician determines the necessity of further evaluation and diagnostic imaging.

The first task is to identify those patients at risk for significant renal injuries. Mee et al. published the classic article establishing criteria for the evaluation of blunt renal trauma. This 10-year prospective study of 1,007 consecutive blunt trauma patients established markers associated with increased risk of major renal lacerations. Gross hematuria, microscopic hematuria (>5 red blood cells [RBCs]/high power field [HPF]) with shock either in the prehospital setting or in the ED, or, less commonly, a history of significant deceleration, are associated with renal injuries. The authors concluded that if radiographic evaluation were limited to those patients, no significant renal injuries would be missed (11). These guidelines have been supported by subsequent studies and have become the criteria defining the population of patients who require further radiographic evaluation (2,3,12). While children are more prone to renal injuries than adults because the pediatric kidney is proportionally larger and has less protection from surrounding tissues, the same criteria screening used to image adult patients may be appropriately applied to pediatric patients (13,14). Most authors advocate radiologic imaging in the setting of penetrating trauma to evaluate for upper urinary tract injuries, as a substantial percentage of patients may have significant injury in the absence of hematuria (2,3).

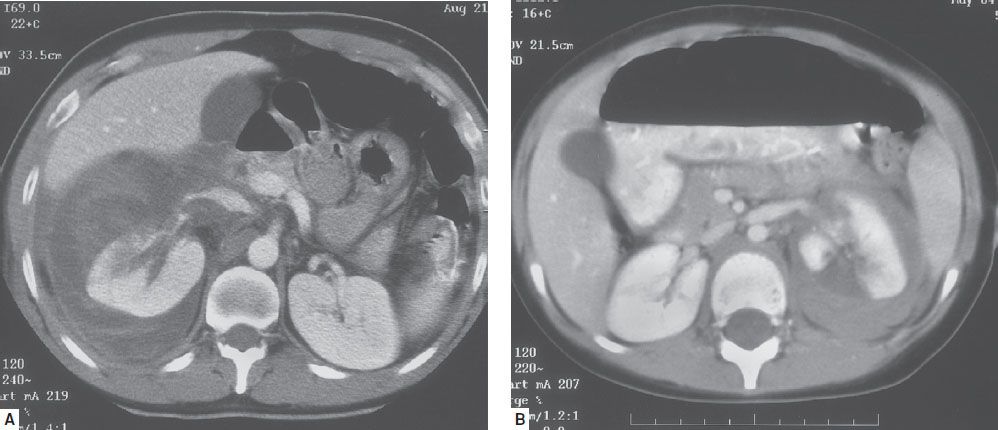

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the preferred diagnostic modality for evaluating the hemodynamically stable patient with blunt or penetrating trauma. CT clearly defines parenchymal lacerations, hematomas, and the presence of urinary extravasation; may identify renal vascular injuries; and can identify associated injuries (Fig. 35.3). Significant findings on CT scan include a devitalized renal segment, a nonfunctioning kidney, actively expanding hematoma, or extravasation of urine. Nonfunction suggests extensive trauma to the kidney, renal artery thrombosis, or a severely shattered kidney. Extravasation of contrast material implies trauma involving the capsule, parenchyma, or collecting system.

FIGURE 35.3 Renal lacerations with perirenal hematoma.