INTRODUCTION

Falls, assaults, motor vehicle crashes, and sports injuries are the most common mechanisms for blunt genitourinary injuries, whereas gunshot wounds and stab wounds are the most common causes for penetrating injuries.1 The majority of ureteral injuries are caused by penetrating trauma.1,2 Bladder injuries are typically caused by pelvic fracture, with urethral injuries seen in 5% to 10% of pelvic fractures.1,3 Children are more susceptible to genitourinary injury than the general population. Children lack periadipose tissue, and kidney size is large relative to overall body size.4 Appropriate management will minimize or prevent complications such as renal function impairment, urinary incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Obtain a detailed history to determine the time and mechanism of injury and the magnitude of forces involved. In motor vehicle crashes, seat location, use of restraints, vehicle speed, and crash details provide information about forces applied to the victim. Sudden deceleration can cause major vascular disruption and parenchymal damage to the kidneys and bladder, even in the absence of symptoms and physical findings. For penetrating trauma, obtain information about the caliber of weapon or type of knife, its length, any contamination, and whether removed intact.

An inability to urinate may be due to an empty bladder or inability to void because of pain, but can also result from bladder perforation, urethral injury, or spinal cord injury.

Inspect the perineum during the secondary survey. Blood on the underwear or pants is an important finding and may suggest genital trauma. Inspect the folds of the buttocks for ecchymoses, abrasions, or lacerations, which may be related to an open pelvic fracture. Do not deeply probe perineal injuries because probing could disrupt a clot.

Rectal examination identifies sphincter tone, position of the prostate gland, and presence of blood. If the prostate is “missing” or riding high or feels boggy, assume disruption of the membranous urethra until proven otherwise. In males, examine the scrotum for ecchymoses, laceration, and testicular disruption. Palpate and inspect the penis for ecchymoses, deformity, and blood at the meatus. In females, examine the vaginal introitus for lacerations and hematomas. Lacerations and hematomas can accompany pelvic fracture. Perform a speculum examination when vaginal bleeding or hematoma is present to exclude vaginal laceration. Complications of missed vaginal injuries include infection, fistula formation, and hemorrhage.

KIDNEY INJURIES

Renal injury is present in up to 10% of patients with abdominal trauma.1,3 Because of the protected position of the kidneys, most injuries are associated with other intra-abdominal injuries.5 Flank contusions or ecchymosis, palpable mass, lower rib fractures, and penetrating wounds in the flank mandate consideration of renal injury. Renal injuries consist of lacerations, avulsions, and hematomas to the kidney itself and renal pelvis. Renal vascular injuries (avulsion, laceration, occlusion) are uncommon but must be considered in the specific diagnosis of kidney injury.6

Although urinalysis is a commonly ordered laboratory study for suspected renal injury, there is no direct relationship between the presence, absence, or degree of microscopic hematuria and the severity of injury.1,3,5 Microscopic and dipstick urinalysis are equally reliable for detecting the presence of hemoglobinuria.5,7 However, renal pedicle injuries and segmental arterial thrombosis may be present without hematuria. In blunt trauma, there is some evidence suggesting that gross hematuria has predictive value for more severe renal injury.1,5,7 In addition, patients with a systolic blood pressure of <90 mm Hg and microscopic hematuria have a higher likelihood of significant injury.1,5 Children with <50 red blood cells per high-powered field have a low likelihood of significant renal injury.5

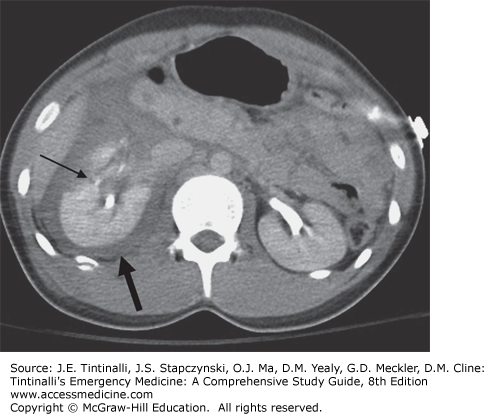

The main objectives of imaging are to (1) accurately stage the renal injury, (2) recognize preexisting pathology of the injured kidney, (3) document the function of the opposite kidney, and (4) identify associated injuries to other organs.5 Imaging guidelines are listed in Table 265-1. An IV contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the imaging “gold standard” for the sTable patient with suspected renal injury.5,8,9 Contrast-enhanced CT detects contusion, lacerations, hematomas, and perfusion abnormalities (Figure 265-1). Early contrast extravasation is consistent with ongoing hemorrhage. However, urinary extravasation cannot be detected until the contrast-enhanced urine is excreted into the collecting system, which usually can take up to 10 minutes. Therefore, a delayed scan of the kidney, ureter, and bladder is recommended to exclude urinary extravasation from any source. If the kidney is normal and there is no abnormal fluid collection in the perinephric, retroperitoneal, or peripelvic areas, then the delayed scan can be omitted.

| Injury | Imaging | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Multisystem trauma or suspected renal parenchymal or vascular injury | Abdominal-pelvic IV contrast CT scan | Include pelvis to view entire GU tract Delayed films needed to identify urinary extravasation |

| Any visceral injury resulting in free intraperitoneal fluid | FAST | Identifies free fluid, but does not specify type of visceral injury and does not identify renal vascular injury |

| Renal artery injury | Renal angiography | Details vascular injuries |

| Ureteral injury | Abdominal-pelvic IV contrast CT scan | Delayed films needed to identify extravasation; obtain IV pyelogram or retrograde pyelogram if still suspicious with negative CT |

| Bladder injury | Retrograde cystogram | Can use plain radiographs or CT scan |

| Urethral injury | Retrograde urethrogram | Discuss sequencing with radiologist, because if performed prior to abdominal-pelvic contrast CT scan, can interfere with diagnosis |

| Scrotal/testicular injury | Color Doppler US | Contrast-enhanced US or MRI if suspicion is high and initial US is negative |

The focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination is useful for identifying free intraperitoneal fluid, but does not specifically evaluate renal injury. FAST does not identify renal vascular injury. US examination may be useful for identifying and following postoperative fluid collections and for patients who are managed without operative intervention.8,9

Renal angiography can identify vascular injuries. Embolization of appropriate injuries can then be accomplished. Embolization can also be used to treat delayed traumatic arteriovenous fistulas.

Grading of the renal injury is based on the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma organ injury scale (Table 265-2).10 This grading system correlates with the need for operative repair and nephrectomy. In a study of 2467 patients with renal trauma, 86.5% were grade I, 3.5% grade II, 4.8% grade III, 4.0% grade IV, and 1.1% grade V. The rate of nephrectomy ranged from 0% for grades I and II to 82% for grade V.11 Decreased kidney function is also directly correlated with renal injury grade.12

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Hematuria with normal anatomic studies (contusion) or subcapsular, nonexpanding hematoma; no laceration |

| II | Perirenal, nonexpanding hematoma or <1 cm renal cortex laceration with no urinary extravasation |

| III | >1 cm renal cortex laceration with no collecting system involvement or urinary extravasation |

| IV | Laceration through cortex and medulla and into collecting system or segmental renal artery or vein injury with hematoma |

| V | Shattered kidney or vascular injury to renal pedicle or avulsed kidney |

Absolute indications for renal exploration and intervention include life-threatening hemorrhage due to a renal injury; expanding, pulsatile, or noncontained retroperitoneal hematoma (thought to be from a renal avulsion injury); and a renal avulsion injury (grade V vascular injury) demonstrated on imaging studies.5,7,8 High injury grade, high injury severity score, large blood transfusion requirement, and hemodynamic instability are predictive of the need for nephrectomy. Urinary extravasation alone is not an indication for exploration because it resolves spontaneously in the majority of cases. Extravasation from a renal pelvis or ureteral injury, however, does require repair.

Most authorities agree that grade I, II, and III renal injuries can be handled nonoperatively. Selected grade IV and V parenchymal injuries may be managed nonoperatively, although many of these patients have other indications for operative intervention.

If the trauma patient is hemodynamically sTable and there is suspicion for renal injury with or without gross hematuria or if the patient has a penetrating injury, then CT imaging is indicated. If the CT scan reveals no renal pelvis, vascular, or ureteral injury and the patient remains clinically stable, then observe until the gross hematuria clears. If the CT scan reveals a renal pelvis, vascular, or ureteral injury, then surgical consultation is indicated.

Many gunshot and stab wounds to the kidneys can be treated nonoperatively. The absolute indications for operation remain those listed previously. Many patients with renal injuries have associated injuries that mandate operative intervention.

Renal vascular injury is identified on CT scanning and requires emergent surgical consultation in order to arrange treatment to minimize the time of renal ischemia. The optimal time to revascularization is not clear, with recommendations for timing of definitive treatment ranging from 4 to 20 hours.6 Follow local institutional urology and trauma protocols once renal vascular injury is identified.

Complications that may result from renal trauma include delayed bleeding, urinary extravasation, urinoma, perinephric abscess, and hypertension and failure of the affected kidney. Delayed bleeding can occur up to a month after injury and is most commonly due to an arteriovenous fistula that has developed after a deep parenchymal laceration. Arteriovenous fistula occurs in up to 25% of cases of grade III or IV injuries that are managed conservatively.5,13 Most can be managed with angiographic embolization, but renorrhaphy or nephrectomy may be necessary.8,13 A urinoma may develop from a few weeks to many years after injury and may have no symptoms or may cause a feeling of abdominal discomfort, mass, or low-grade fever. Treatment is usually percutaneous drainage or ureteral stenting. A perinephric abscess can present similarly and can also be treated with percutaneous drainage. Hypertension may occur due to renal artery injury, devascularized tissue, renal parenchymal compression by clot, or by arteriovenous malformation, and may occur from days to many years after injury. Nephrectomy is the most common treatment, but medical management may be indicated.

Most patients with significant renal injury are admitted on the basis of associated injuries. For patients with isolated renal trauma, few data support specific recommendations for disposition and follow-up.

Patients with isolated renal trauma and a class I injury can be separated into two groups after urology consultation. Those with a renal contusion (microscopic hematuria with normal imaging) can be discharged home as above. Patients with a subcapsular hematoma can be admitted for a short observation stay followed by a hematocrit and clinical reevaluation. Patients with gross hematuria usually need admission and require bed rest until the gross hematuria clears. Admit patients with grade II or higher injury to the hospital under the care of a trauma surgeon, general surgeon, or urologist as appropriate for the practice setting.

URETERAL INJURIES

Isolated ureteral injury is rare in trauma patients because the ureter is well protected in the retroperitoneum.14,15 Approximately 80% of ureteral injuries occur from intraoperative, iatrogenic damage. Of the 20% of injuries due to external trauma, almost 90% occur as a result of penetrating trauma (81% gunshot wounds, 9% stab wounds) and 10% occur due to blunt trauma.14,15 Because there are no history or physical examination findings that are specific for ureteral injuries, these injuries can be easily missed.7 Approximately 70% of patients with ureteral injuries have either gross or microscopic hematuria. The absence of hematuria does not exclude ureteral injury.2,7,14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree