GENITOURINARY EMERGENCIES

DANA A. WEISS, MD AND CYNTHIA R. JACOBSTEIN, MD, MSCE

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Children present to the emergency department (ED) with a wide range of urologic complaints. Some are truly emergent, and some are a source of concern but can be handled with simple care and reassurance. The ability to triage and treat urologic emergencies is crucial for the ED physician. There are only a few true urologic emergencies that must be managed expeditiously: testicular torsion and a febrile obstructing kidney stone top the list. In addition, conditions such as paraphimosis and priapism warrant acute attention, while other conditions may require only assurance and close urologic follow-up.

KEY POINTS

Identification of true urologic emergencies (testicular torsion, febrile obstructing stone).

Identification of true urologic emergencies (testicular torsion, febrile obstructing stone).

Judicial use of imaging in the diagnosis of urgent urologic conditions.

Judicial use of imaging in the diagnosis of urgent urologic conditions.

The value of triage: the expedited versus routine follow-up urologic care.

The value of triage: the expedited versus routine follow-up urologic care.

Complete genitourinary examination is crucial for all abdominal pain presentations.

Complete genitourinary examination is crucial for all abdominal pain presentations.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Urinary Frequency: Chapter 74

• Vaginal Bleeding: Chapter 75

• Vaginal Discharge: Chapter 76

Clinical Pathways

• Abdominal Pain in Postpubertal Girls: Chapter 82

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

PENILE PROBLEMS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• It is important to distinguish normal physiologic appearance from pathology.

• Paraphimosis and priapism are true emergencies.

Penile Care in the Uncircumcised Male Infant

Goals of Treatment/Clinical Assessment

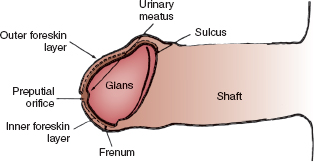

With the high rate of circumcision in the United States, the recommended care of an intact foreskin is not always clear. In uncircumcised male infants, adhesions between the glans and the foreskin are normal (Fig. 127.1). The foreskin is not normally retractable in this age group. No effort should be made to strip the foreskin back in infants because this produces undue pain for the child and may result in inflammation and scarring. Between ages 2 and 4, spontaneous lysis of the adhesions occurs in 90% of boys. It is rare for the male infant to have any adverse hygienic consequence from leaving the foreskin in place until that time. The small, whitish lumps that may be seen and felt beneath the foreskin represent desquamated epithelium, smegma, and are benign. After toilet training, boys should be taught to retract the foreskin enough to expose the meatus during voids—this avoids leaving the inner foreskin wet with urine, which can lead to inflammation, mucosal abrasions, and balanoposthitis. By age 4 to 6 years, the foreskin should be drawn back as far as it can go at every bath.

Postcircumcision Concerns

Immediate Concerns

While rare, postcircumcision bleeding can be of significant concern, or it can be a minor issue. After circumcision done either with a clamp (in the newborn time period), or freehand (older boys), most postoperative bleeding will resolve with manual pressure for 5 to 10 minutes. After that, careful inspection will reveal if there is a discrete vessel bleeding, or if there is more general oozing of blood from the suture line.

Urology consultation is recommended if there is concern for injury to the glans or urethra or if bleeding does not stop with manual pressure.

Delayed Concerns

If there is concern for a skin cicatrix, a thick scar around the edge of the circumcision, encasing the urethral meatus, then the patient should be referred to the urology clinic for outpatient follow-up. This can be done as a routine visit unless there is concern for obstruction of the urinary stream, although this is very rare. If a scar is caught early it may respond to gentle release of flimsy adhesions, or, if a more robust scar, it may respond to treatment with betamethasone cream. In severe cases, a circumcision revision will have to be performed in order to release the scar around the glans.

FIGURE 127.1 Anatomy of normal uncircumcised male. Adhesions between inner foreskin layer and glans are normal in newborns and prevent retraction of the foreskin. (From Wallerstein E. Circumcision: an American health fallacy. New York, NY: Springer, 1980:201. Reprinted with permission.)

Phimosis and Paraphimosis

Goals of Treatment

Rule out significant skin or glans infection in cases of phimosis

Rule out significant skin or glans infection in cases of phimosis

Reduce foreskin back to normal anatomic location in paraphimosis

Reduce foreskin back to normal anatomic location in paraphimosis

Clinical Considerations

Phimosis exists when the distal foreskin becomes scarred so that it cannot be retracted to expose the glans. This nonretracted foreskin is a normal physiologic finding in the newborn and infant. However, this can also persist or occur later in life as a result of inflammation from chronic urine exposure, previous forceful withdrawing of the foreskin over the glans, or related to lichen sclerosus. Children may present with swelling of the foreskin, or with the complaint of seeing ballooning of the foreskin during urination.

Paraphimosis is the result of retracting foreskin behind the glans and leaving it in that position. This leads to venous congestion and edema—thus making it difficult to reduce the foreskin back to its normal position (Fig. 127.2). This often results after bathing (often by a provider not used to caring for the child), or is caused by the child himself. In iatrogenic settings, this may occur after urethral catheterization, when the foreskin is retracted for the procedure but is not returned to its normal position.

FIGURE 127.2 Paraphimosis—a foreskin that is left in a retracted position leads to venous congestion and edema of the foreskin.

Clinical Recognition. A tight phimosis can result in ballooning of the foreskin during voiding, which in turn traps urine and can lead to inflammation. In a child over 2 years old, the foreskin should be able to be retracted to the point where the urethral meatus can be visualized.

Paraphimosis is evident as a broad, edematous band of skin proximal to the glans. This skin is often erythematous and very tender to touch.

Management. Phimosis does not have to be treated emergently. Betamethasone cream, 0.05%, applied twice daily for 6 weeks, is the first-line treatment. Hydrocortisone cream is an alternative. The patient/family must be instructed to pull the foreskin back as far as it will go, then to apply a small amount directly to the tightened area.

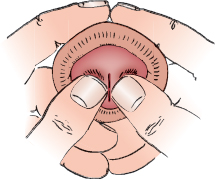

The goal in paraphimosis is to bring the foreskin back into normal location. This requires reduction of the edema in the skin. The application of ice and steady manual compression on the inflamed ring of foreskin usually reduces the edema and permits manual reduction of the paraphimosis. Topical anesthetic cream or a dorsal penile nerve block will reduce the discomfort experienced by the child during compression of the edematous foreskin. Once a portion of the edema has been reduced, pressure on the glans (like turning a sock inside out) usually permits reduction of the foreskin back to its normal position (Fig. 127.3). If manual reduction fails, a surgical division of the foreskin to permit reduction is indicated; however it is uncommon to need to perform this (Fig. 127.4). The family should be counseled not to pull the foreskin back over the glans for at least a week. Vaseline can be applied to the raw edges of the foreskin, especially in the setting of small abrasions, to prevent infection. The family can be counseled about circumcision, although this is not required.

Meatal Stenosis

Meatal stenosis is a problem seen exclusively in circumcised males and follows an inflammatory reaction around the meatus. This can occur from the lower edge of the meatus rubbing against a wet diaper, with inflammation of the meatus resulting from mechanical and ammoniacal chemical dermatitis. Appearances are often deceiving. The meatus may appear to be stenotic but may be functioning adequately. Significant meatal stenosis causes spraying of the urinary stream or, more commonly, dorsal deflection of the stream. Surgical treatment of the meatus is warranted only if these symptoms are present. Meatal stenosis is not a cause of frequency, enuresis, or urinary tract infection. If symptomatic, a boy should be referred to the urology clinic for evaluation and possible meatotomy in the office or a meatoplasty under anesthesia.

FIGURE 127.3 Manual reduction of paraphimosis. After a local anesthetic block of the dorsal nerve of the penis, the foreskin is manually compressed to reduce edema. The foreskin can be reduced by pressure on glans—like turning a sock inside out. (From Klauber GT, Sant GR. Disorders of the male external genitalia. In: Kelalis PP, King LR, Belman AB, eds. Clinical pediatric urology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1985:287. Reprinted with permission.)

FIGURE 127.4 Surgical correction of phimosis. A: Constricting foreskin is incised vertically on dorsum. B: The incision opens laterally, relieving constriction. C: Incision is closed transversely with chromic catgut sutures. D: Foreskin can now be reduced. (From Klauber GT, Sant GR. Disorders of the male external genitalia. In: Kelalis PP, King LR, Belman AB, eds. Clinical pediatric urology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1985:827. Reprinted with permission.)

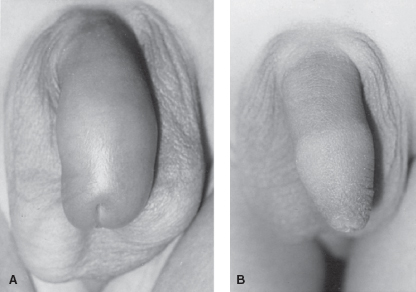

Balanoposthitis

Balanoposthitis is an infection of the foreskin that may extend onto the glans (Fig. 127.5). It is a form of cellulitis and has its origin from a break in the penile skin. It may be the result of local trauma or may, in the older boy, be associated with poor penile hygiene. Scarring after the inflammatory reaction may lead to true phimosis.

Goals of Treatment

Treat active infection and establish follow-up to assess cause of infection.

Treat active infection and establish follow-up to assess cause of infection.

Clinical Recognition

Acute swelling, blanching erythema, and pain likely indicates balanitis or balanoposthitis (infection of the foreskin and the glans). Other etiologies of penile swelling must be considered as well. Isolated penile edema that is either nontender or minimally tender can occur as a result of an insect bite, with local edema secondary to histamine release. A history of a bite or the finding of a small punctate lesion may give the clue to diagnosis. Painless penile edema may also be present with a generalized allergic reaction or as part of the manifestation of a general edematous state secondary to renal, cardiac, or hepatic problems. Here, the diagnosis is suggested by evidence of dysfunction in these organ systems on general examination.

Management

In the setting of true cellulitis, the administration of an appropriate antibiotic is warranted. The antibiotic, for example, cephalexin (clindamycin if cephalosporin allergy) should cover typical skin flora. In addition, local care may be done with warm soaks. It is unusual for a child to be unable to void as a result of this condition, although he may be more comfortable voiding while in a tub of warm water. After resolution of the acute infection, the boy should be reexamined for signs of phimosis. If a severe phimosis develops, or if there is a history of recurrent episodes of balanitis, then a circumcision may be recommended.

FIGURE 127.5 A: Balanoposthitis—cellulitis of normal foreskin with erythema, edema, and tenderness. B: Normal foreskin after treatment of balanoposthitis with antibiotics and warm soaks.

Priapism

Prolonged, painful penile erection unaccompanied by sexual stimulation is called priapism. Generally an erection lasting longer than 4 hours requires treatment. Pain that occurs prior to 4 hours is an additional indication for initiation of treatment.

Goals of Treatment

Achieve detumescence

Achieve detumescence

Identify and/or treat underlying pathology

Identify and/or treat underlying pathology

Clinical Recognition

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree