INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes selected serious generalized skin disorders in adults and discusses their dermatologic diagnosis and treatment. Covered are erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, exfoliative erythroderma, the toxic infectious erythemas, disseminated viral infections, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, disseminated gonococcal infection, purpura fulminans, and pemphigus vulgaris. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and meningococcemia are discussed in the pediatric section, in chapter 141, “Rashes in Infants and Children.” Staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome are also discussed in chapter 150, “Toxic Shock Syndromes.” Disseminated viral infections are discussed in chapter 153, “Serious Viral Infections” and in chapter 141.

The disorders erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, exfoliative erythroderma, staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome share some features in common. Table 249-1 can help in differentiating these disorders.

| Disorder | Appearance | Special Features |

|---|---|---|

| Erythema multiforme | Erythematous macules, papules Target lesions Urticaria or vesiculobullous lesions | Cutaneous reaction to drugs or infectious agents. Stevens-Johnson syndrome is the most severe form. |

| Toxic epidermal necrosis | Painful, tender erythroderma Vesicles and bullae Exfoliation | Nikolsky sign present. Stevens-Johnson syndrome is most severe form. Drugs most common cause. |

| Exfoliative erythroderma | Nontender erythema Skin flaking and scaling Thickening of skin | Often preexisting eczema or psoriasis; can be drug induced. |

| Staphylococcal or streptococcal toxic shock syndrome | Staphylococcal: fine punctuate erythematous lesions that become confluent; blanching erythroderma; desquamation first of trunk and face, then extremities Streptococcal: can be indistinguishable from staphylococcal toxic shock; scarlatiniform erythroderma with sheet-like desquamation of skin | Colonization or infection with Staphylococcus aureus; menstruation associated with tampon use; nonmenstrual associated with burns, cellulites, sinusitis, wounds, etc. Group A streptococcal cellulitis, puerperal sepsis, any group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus infection source. |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | Scarlatiniform rash or erythema Bullae or bullous impetigo Sloughing of skin | Usually seen in neonates or children <5 years of age. Nikolsky sign present. |

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

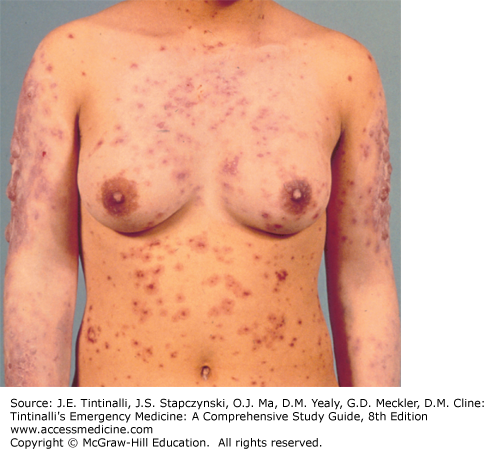

Erythema multiforme is an acute inflammatory skin disease ranging from a localized papular eruption of the skin (erythema multiforme minor) to a severe, multisystem illness (Figure 249-1) with widespread vesiculobullous lesions and erosions of the mucous membranes, known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The spectrum is defined by the amount of epidermal detachment present, with erythema multiforme minor having no epidermal detachment, Stevens-Johnson syndrome having <10% of the body surface area with epidermal detachment, overlapping of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis having 10% to 30% epidermal detachment, and toxic epidermal necrolysis having >30% epidermal detachment.1 Morbidity and mortality rise with the amount of epidermal detachment.2 The highest incidence is in young adults (age range, 20 to 40 years), and erythema multiforme occurs commonly in the spring and fall. Common precipitating factors are infection, especially with Mycoplasma and herpes simplex virus; drugs, especially antibiotics and anticonvulsants; and malignancies. However, the cause is often unknown.3 Most likely, erythema multiforme is the result of a hypersensitivity reaction, with immunoglobulin and complement components demonstrated in the cutaneous microvasculature on immunofluorescent studies of skin biopsy specimens, circulating immune complexes found in the serum, and mononuclear cell infiltrate noted on histologic examination.3,4

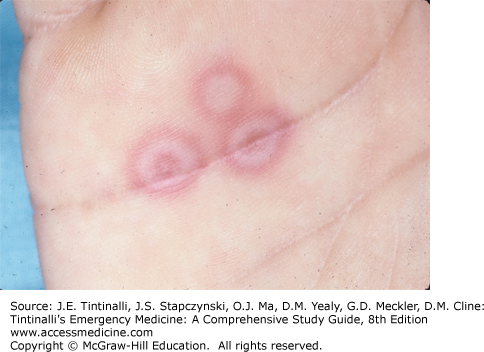

Symptoms include malaise, fever, myalgias, and arthralgias. Diffuse pruritus or a generalized burning sensation can occur before the skin lesions develop. The morphologic configuration of the lesions is variable, hence the descriptor multiforme. Maculopapular (Figure 249-2) and target, or iris (Figure 249-3), lesions are the most characteristic. Erythematous papules appear symmetrically on the dorsum of the hands and feet and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. The maculopapule evolves into the classic target lesion during the next 24 to 48 hours. As the maculopapule enlarges, the central area becomes cyanotic, occasionally accompanied by central purpura or a vesicle. Urticarial plaques also may occur with or without the iris lesion in a similar distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions, which may be pruritic and painful, develop within preexisting maculopapules or plaques, usually on the extensor surface of the arms and legs and less frequently on the trunk. Vesiculobullous lesions are found most often on mucosal surfaces, including the mouth, eyes, vagina, urethra, and anus; they may also be seen on the trunk. Ocular involvement occurs in approximately 9% of patients with erythema multiforme minor, whereas ophthalmologic lesions are seen in almost 70% of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.5 The various lesions (Table 249-2) develop in successive crops during a 2- to 4-week period and heal over 5 to 7 days. The differential diagnosis of erythema multiforme includes herpetic (herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus) infection, vasculitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, various primary blistering disorders (pemphigus and pemphigoid), urticaria, Kawasaki’s disease, and the toxic and infectious erythemas.

| Lesions of Erythema Multiforme | Lesions of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis |

|---|---|

| Erythematous maculopapules | Warm, tender erythroderma |

| Iris or target lesions | Vesicles and bullae |

| Urticaria | Exfoliation |

| Mucous membranes involved | Mucous membranes involved |

Recurrence may be noted on repeat exposure to the etiologic agent, a special concern in cases associated with herpes simplex virus infection or medication use.6 The rate of erythema multiforme recurrence is very high in children with herpes simplex virus infection. For example, 75% of children with a history of herpes simplex virus–related erythema multiforme developed erythema multiforme recurrence after herpes simplex virus reactivation.6 Fluid and electrolyte disorders and secondary infection from cutaneous sites are the most frequent complications.

Systemic steroids are commonly used for localized disease and provide symptomatic relief but are of unproven benefit in influencing the duration and outcome of erythema multiforme.7 Many authorities recommend a short, intensive steroid course of prednisone, 60 to 80 milligrams PO once a day, particularly in drug-related cases, with abrupt cessation in 3 to 5 days if no favorable response is noted. Systemic analgesic agents and antihistamines provide symptomatic relief. Stomatitis is treated with diphenhydramine and viscous lidocaine mouth rinses. Do not swallow oral viscous lidocaine because it causes neurotoxicity. Treat blisters with cool compresses of Burow solution (5% aluminum acetate). Ocular involvement should be monitored by an ophthalmologist. Unfortunately, burst steroid therapy does not reduce the chance of development or significance of existing ocular lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree