GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

LENORE R. JARVIS, MD, MEd AND STEPHEN J. TEACH, MD, MPH

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a relatively common problem in pediatrics. Over one 12-month study period at a large urban pediatric emergency department, complaints of rectal bleeding accounted for 0.3% of all visits. Upon the patient’s arrival, the emergency physician must first assess the need for cardiovascular resuscitation and stabilization. However, most children who arrive in the ED with an apparent GI bleed have an acute, self-limited GI hemorrhage and are hemodynamically stable.

In most cases of upper and lower GI bleeding, the source of the bleeding is inflamed mucosa (infection, allergy, drug induced, stress related, or idiopathic). The emergency physician must be vigilant in differentiating inflammatory conditions that are often self-limited from causes that may require emergent surgical or endoscopic intervention, such as ischemic bowel (intussusception, volvulus), structural abnormalities (Meckel diverticulum, angiodysplasia), and portal hypertension (esophageal varices). Acute GI bleeding rarely represents a surgical emergency. In the previously noted study, only 4.2% of 95 patients required a blood transfusion or an operative intervention.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

The clinician should sequentially assess the patient through the following questions:

1. Is the patient in hemorrhagic shock (see Chapter 5 Shock for signs of hemorrhagic shock)?

2. Is the patient really bleeding? Is the bleeding coming from the GI tract? If so, how severe is the bleeding?

3. Is it upper or lower GI bleeding?

4. What is the age-related differential diagnosis based on pertinent history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests?

GI Bleed Imitators

Many substances ingested by children may simulate fresh or chemically altered blood. Red food coloring (found in cereals, antibiotics and cough syrups, Jell-O, and Kool-Aid), as well as fruit juices and beets, may resemble blood if vomited or passed in the stool. Medications such as antibiotics (cefdinir—which can cause “brick red” stools), iron supplementation, and bismuth (in Pepto-Bismol) may cause the stool to look melanotic or bloody. Foods such as dark chocolate, spinach, cranberries, blueberries, grapes, or licorice may also produce dark-colored stools. In these cases, confirmation of the absence of blood with Gastroccult (vomitus) or Hemoccult (stool) tests will allay parental anxiety, as well as prevent unnecessary concern and testing.

A careful search for other causes of presumed GI bleeding (recent epistaxis, dental work, menses, and hematuria) should be sought. Hematemesis (vomiting of blood) also needs to be differentiated from hemoptysis (bleeding from the airways).

Severity of Bleeding

Estimation of blood loss (a few drops, a spoonful, a cupful, or more) should be ascertained on initially although this can be difficult and inaccurate. Hemoglobin and hematocrit are also unreliable estimates of acute blood loss because of the time required for hemodilution to occur after an acute hemorrhage. The estimated volume of blood loss should be correlated with the patient’s clinical status. In pediatrics, a patient may lose 15% of their circulating blood volume prior to changes in the vital signs. The presence of resting tachycardia, pallor, prolonged capillary refill time, and metabolic acidosis point to significant enteral blood loss. Hypotension is a late finding in young children, typically after greater than 30% of blood volume has been lost, and should be treated as hemorrhagic shock demanding immediate resuscitative measures (intravenous fluids and blood transfusion).

Children with only a few drops or flecks of blood in the vomit or stool should not be considered “GI bleeders” if their history and physical examinations are otherwise unremarkable. Caution must be taken, however, as small amounts of blood (whether in emesis or passed per rectum) may be the harbinger of more extensive enteral bleeding.

Establishing the Level of Bleeding

There are two general categories of GI bleeding: upper and lower. Upper GI bleeding refers to bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz. Twenty percent of GI bleeds in pediatrics are from the upper GI tract. Lower GI bleeding is distal to the ligament of Treitz. In most cases, the clinical findings along with nasogastric lavage will delineate the cause of bleeding within the GI tract. Hematemesis, defined as the vomiting of blood, can range from fresh and bright red to old and dark with the appearance of “coffee grounds” (due to the effect of gastric acidity). Hematochezia, the passage of bright red blood per rectum, suggests lower GI bleeding or upper GI bleeding with a very rapid enteral transit time (such as in infants). Melena, the passage of stool that is shiny, black, and sticky, reflects bleeding from either the upper GI tract or the proximal large bowel. In general, the darker the blood in the stool, the higher it originates in the GI tract (or, alternatively, the longer it has resided in the GI tract). “Currant jelly” stools indicate vascular congestion and hyperemia of the colon with passage of blood mixed with mucus, as seen with intussusception. Maroon-colored stools generally occur with a voluminous bleed anywhere proximal to the rectosigmoid area, such as seen with a Meckel diverticulum.

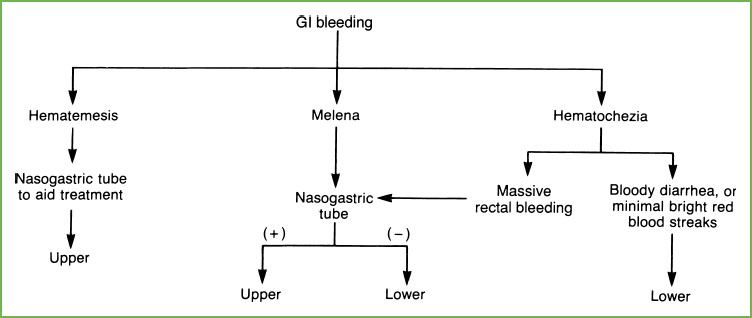

Patients with a significant bleeding episode should have a nasogastric tube placed for a diagnostic saline lavage (Fig. 28.1). In patients with hematemesis or melena, a nasogastric aspirate yielding blood confirms an upper source of GI bleeding, whereas a negative result almost always excludes an active upper GI bleed. Occasionally, a postpyloric upper GI lesion, such as a duodenal ulcer, bleeds massively without reflux into the stomach, resulting in a negative aspirate. In such a case, an upper GI endoscopy will detect such a lesion. Patients with significant hematochezia or melena should likewise have a nasogastric tube placed. As noted above, because blood can exert a cathartic action, brisk bleeding from an upper GI lesion may induce rapid transit through the gut, thus preventing blood from becoming melanotic. In patients with hematochezia manifested as bloody diarrhea or minimally blood-streaked stools, a lower GI source should be investigated.

FIGURE 28.1 Establishing level of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Differential Diagnosis

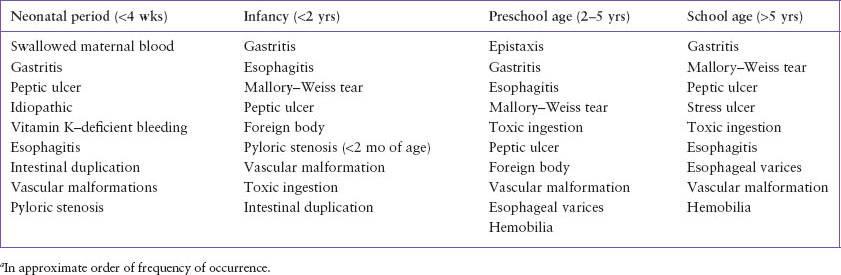

As seen in Table 28.1, there is considerable overlap between age groups and causes of upper GI bleeding. Mucosal lesions, including esophagitis, gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and Mallory–Weiss tears, are the most common sources of GI bleeding in all age groups (Table 28.2; see Chapter 99 Gastrointestinal Emergencies). Of all cases of upper GI bleeding in children, 95% are related to mucosal lesions and esophageal varices. Coagulation disorders (e.g., disseminated intravascular coagulation, Von Willebrand disease, hemophilia, thrombocytopenia, liver failure, uremia, and factor deficiencies) should also be considered for all age groups as a cause of bleeding, but will not be discussed in detail in this chapter (see Chapter 101 Hematologic Emergencies for further details on coagulation disorders). Life-threatening causes of upper GI bleeding are listed in Table 28.3.

Neonatal Period (0 to 1 Month)

Hematemesis in a healthy newborn most likely results from swallowed maternal blood either at delivery or during breast-feeding. In the breast-fed neonate with new onset of hematemesis and maternal history of cracked nipples, who is well appearing and with normal examination, one approach is to allow the mother to nurse (or use a breast pump) in the ED. Often, when the infant has been at the breast for a few moments and then is pulled away, obvious bleeding from the mother’s nipple is apparent, providing reassurance to both physicians and parents.

TABLE 28.1

ETIOLOGY OF UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING BASED ON AGEa

TABLE 28.2

COMMON CAUSES OF UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING BASED ON AGE

Although less common, gastritis (from stress, sepsis, cow’s milk intolerance, and trauma from nasogastric tube insertion), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and coagulation disorders should be considered. If vitamin K was not administered in the immediate postpartum period, vitamin K–deficient bleeding (previously known as hemorrhagic disease of the newborn) should be considered. Maternal drugs that cross the placenta, including aspirin, phenytoin, and phenobarbital, may also interfere with clotting factors and cause hemorrhage.

Infancy (1 Month to 2 Years)

Common, and often less severe, causes of bleeding in this age group are gastritis and reflux esophagitis. Significant and sometimes massive upper GI hemorrhage in a newborn may occur with no demonstrative anatomic lesion or only “hemorrhagic gastritis” at endoscopy. This is usually a single, self-limited event that is benign if treated with appropriate blood replacement and supportive measures. Other causes of significant hemorrhage may include pyloric stenosis (often at less than 2 months of age, preceded by significant nonbloody emesis), peptic ulceration, a duplication cyst, foreign body, or caustic ingestion.

TABLE 28.3

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Critically ill children of any age are at risk for developing stress-related peptic ulcer disease. Such ulcers occur with life-threatening illnesses, including shock, respiratory failure, hypoglycemia, dehydration, burns (Curling ulcer), intracranial lesions or trauma (Cushing ulcer), renal failure, and vasculitis. These ulcers may develop within minutes to hours after the initial insult and primarily result from ischemia. Hematemesis, hematochezia, melena, and/or perforation of the stomach or duodenum may accompany stress-associated ulcers.

Hematemesis secondary to gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis is uncommon but should be considered in patients who are severely symptomatic with vomiting or aspiration. Hematemesis following the acute onset of vigorous vomiting or retching at any age suggests a Mallory–Weiss tear. These tears occur at the gastroesophageal junction due to a combination of mechanical factors (e.g., retching) and gastric acidity.

Preschool Period (2 to 5 Years)

Idiopathic peptic ulcer disease is a common cause of GI bleeding in preschool and older children. Most preschool children with idiopathic ulcers develop GI bleeding (hematemesis or melena). Complications, including obstruction and perforation, may occur. Younger children have less characteristic symptoms, often localize abdominal pain poorly, and may have vomiting as a predominant symptom. Older children and adolescents describe epigastric pain in a pattern typical of adults. Helicobacter pylori infection has emerged as a leading cause of secondary gastritis, particularly in older children. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetylsalicylic acid can also be a cause of gastritis in this age group.

School Age through Adolescence Period

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree