Gastroesophageal Balloon Tamponade for Acute Variceal Hemorrhage

Marie T. Pavini

Juan Carlos Puyana

Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage is an acute and catastrophic complication that occurs in one third to one half of patients with portal pressures greater than 12 mm Hg [1]. Because proximal gastric varices and varices in the distal 5 cm of the esophagus lie in the superficial lamina propria, they are more likely to bleed and more likely to respond to endoscopic treatment [2]. Variceal rupture is likely a factor of size, wall thickness, and portal pressure, and may be predicted by Child-Pugh class, red wale markings indicating epithelial thickness, and variceal size [1]. Whereas urgent endoscopy, sclerotherapy, and band ligations are considered first-line treatments, balloon tamponade remains a valuable intervention in the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Balloon tamponade is accomplished using a multilumen tube with esophageal and gastric cuffs that can be inflated to compress esophageal varices and gastric submucosal veins thereby providing hemostasis through tamponade.

Historical Development

In 1930, Westphal described the use of an esophageal sound as a means of controlling variceal hemorrhage. In 1947, successful control of hemorrhage by balloon tamponade was achieved by attaching an inflatable latex bag to the end of a Miller-Abbot tube. In 1949, a two-balloon tube was described by Patton and Johnson. A triple-lumen tube with gastric and esophageal balloons (one lumen for gastric aspiration and the other two for balloon inflation) was described by Sengstaken and Blakemore in 1950. In 1953, Linton proposed a single gastric balloon tube with a suction lumen below the balloon as a diagnostic tool to differentiate between gastric and esophageal bleed and a larger balloon (800 mL) capable of compressing the submucosal veins in the cardia, thereby minimizing flow to the esophageal veins. An additional suction port above Linton’s gastric balloon was introduced by Nachlas in 1955. The Minnesota tube was described in 1968 as a modification of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, incorporating the esophageal suction port, which will be described later.

Role of Balloon Tamponade in The Management of Bleeding Esophageal Varices

Treatment of portal hypertension to prevent variceal rupture includes primary and secondary prophylaxis. Primary prophylaxis consists of beta-blockers, band ligation, and endoscopic surveillance, and secondary prophylaxis includes nitrates, trans- jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and surgical shunt [3]. Appropriate management of acute variceal bleeding involves multiple simultaneous and sequential modalities. A number of studies comparing the efficacy of balloon tamponade against sclerotherapy have shown that the incidence and severity of complications and success in controlling bleeding favor the use of sclerotherapy or band ligation as the first line of treatment [4, 5]. The decision to use other therapeutic alternatives depends on the response to the initial therapy, the severity of the hemorrhage, and the patient’s underlying condition.

Splanchnic vasoconstrictors such as octreotide, terlipressin (the only agent shown to decrease mortality), or vasopressin (with nitrates to reduce cardiac side effects) decrease portal blood flow and pressure and should be administered as soon as possible [6, 7 and 8]. In fact, Pourriat et al. [9] advocate administration of octreotide by emergency medical personnel before patient transfer to the hospital. Recombinant activated factor VII has been reported to achieve hemostasis in bleeding esophageal varices unresponsive to standard treatment and may also be considered [10]. Emergent therapeutic endoscopy in conjunction with pharmacotherapy is more effective than pharmacotherapy alone and is also performed as soon as possible. Band ligation has a lower rate of rebleeding and complications when compared with sclerotherapy and should be performed preferentially, provided visualization is adequate to ligate varices successfully [3, 11]. Tissue adhesives such as polidocanol and cyanoacrylate delivered through an endoscope are being used and studied outside the United States.

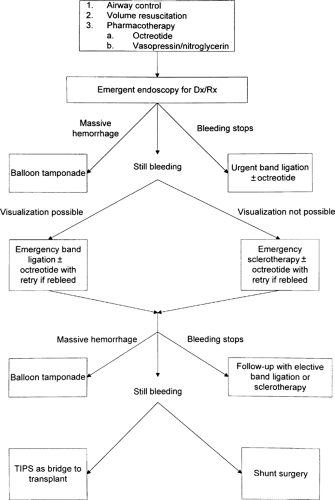

Balloon tamponade is performed to control massive variceal hemorrhage with the hope that band ligation or sclerotherapy and secondary prophylaxis will then be possible (Fig. 15-1). If bleeding continues beyond these measures, then TIPS [12] is

considered. Shunt surgery [13] may be considered if TIPS is contraindicated. Other alternatives include percutaneous transhepatic embolization, emergent esophageal transection with stapling [14], esophagogastric devascularization with esophageal transection and splenectomy, and hepatic transplantation. If gastric varices are noted, therapeutic options include endoscopic administration of the tissue adhesive cyanoacrylate, TIPS, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration [15], balloon-occluded endoscopic injection therapy [16], and devascularization with splenectomy, shunt surgery, and liver transplantation.

considered. Shunt surgery [13] may be considered if TIPS is contraindicated. Other alternatives include percutaneous transhepatic embolization, emergent esophageal transection with stapling [14], esophagogastric devascularization with esophageal transection and splenectomy, and hepatic transplantation. If gastric varices are noted, therapeutic options include endoscopic administration of the tissue adhesive cyanoacrylate, TIPS, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration [15], balloon-occluded endoscopic injection therapy [16], and devascularization with splenectomy, shunt surgery, and liver transplantation.

Indications and Contraindications

A Sengstaken-Blakemore or Minnesota tube is indicated in patients with a diagnosis of esophageal variceal hemorrhage in which neither band ligation nor sclerotherapy is technically possible, readily available, or has failed [17]. If at all possible,

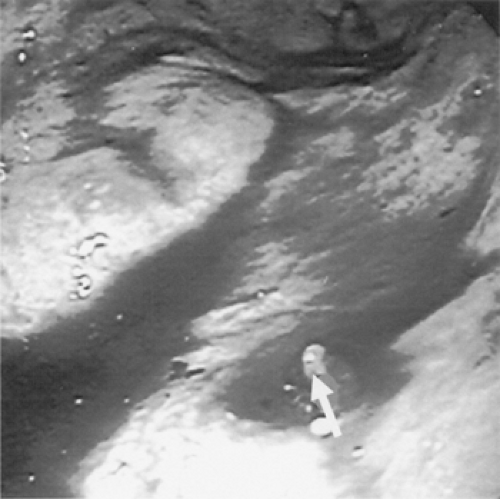

making an adequate anatomic diagnosis is critical before any of these balloon tubes are inserted. Severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding attributed to esophageal varices in patients with clinical evidence of chronic liver disease results from other causes in up to 40% of cases. The observation of a white nipple sign (platelet plug) is indicative of a recent variceal bleed (Fig. 15-2). The tube is contraindicated in patients with recent esophageal surgery or esophageal stricture [18]. Some authors do not recommend balloon tamponade when a hiatal hernia is present, but there are reports of successful hemorrhage control in some of these patients [19].

making an adequate anatomic diagnosis is critical before any of these balloon tubes are inserted. Severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding attributed to esophageal varices in patients with clinical evidence of chronic liver disease results from other causes in up to 40% of cases. The observation of a white nipple sign (platelet plug) is indicative of a recent variceal bleed (Fig. 15-2). The tube is contraindicated in patients with recent esophageal surgery or esophageal stricture [18]. Some authors do not recommend balloon tamponade when a hiatal hernia is present, but there are reports of successful hemorrhage control in some of these patients [19].

FIGURE 15-2. Esophageal varices as seen by endoscopy. The white nipple (arrow) indicates a recent platelet plug. (Courtesy of Dale Janik, MD.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|