CHAPTER 49

Ganglion Impar Block

INDICATIONS

The ganglion impar, also known as the ganglion of Walther or sacrococcygeal ganglion is a singular retroperitoneal structure located at the level of the sacrococcygeal junction (SCJ). It is of particular importance when considering patients who suffer from pain in the pelvic and perineal structures as it provides nociceptive and sympathetic supply to those regions. It receives afferent innervation from the perineum, distal rectum, anus, distal urethra, and distal vagina. Plancarte et al first reported the successful relief of perineal pain through the blockade of the ganglion impar in 1990.1 The initial approach as offered by Plancarte involved a bent spinal needle. Through the years, techniques have evolved with the use of fluoroscopy, computed tomography (CT), and ultrasound, and the utility for its potential relief of patient remains relatively unquestioned.

The indications for blockade based on anatomical location of pain include:

1. Perineal pain, with or without malignancy

2. Rectal/Anal pain (proctitis)

3. Distal urethral pain

4. Vulvodynia

5. Scrotal pain

6. Female pelvic/vaginal pain (distal 1/3)

7. Sympathetically-maintained pain to the region (ie, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome)

8. Endometriosis

9. Chronic prostatitis

10. Proctalgia Fugax

11. Coccygodynia2

12. Radiation proctitis3

13. Postherpetic neuralgia4

14. Burning and localized perineal pain associated with urgency

RELEVANT ANATOMY

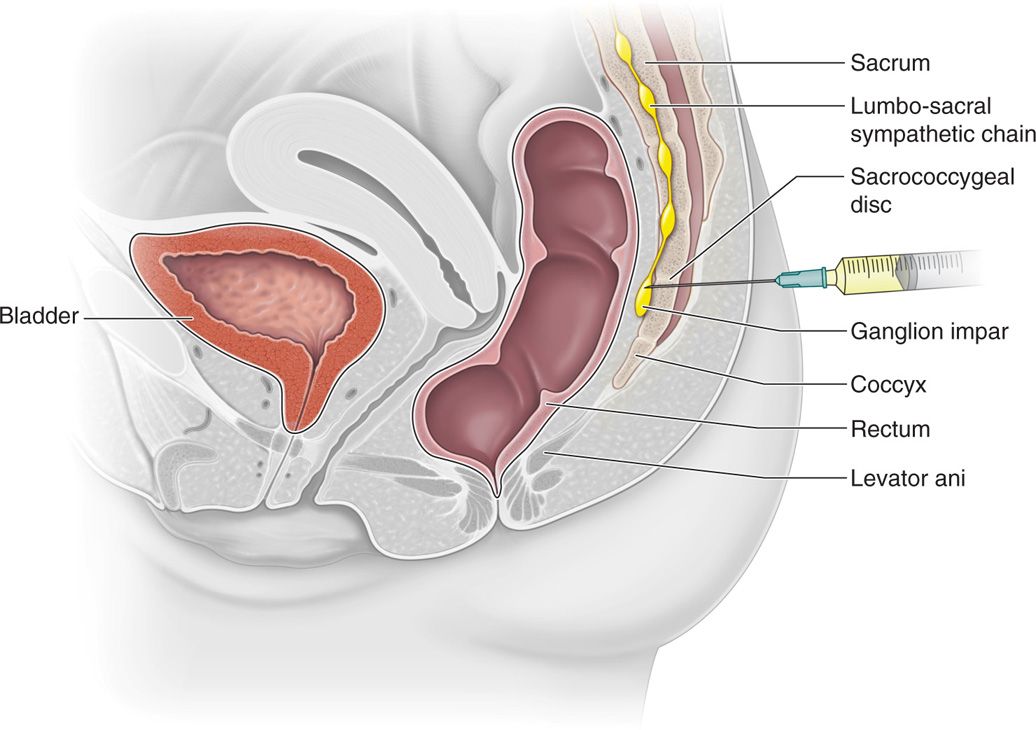

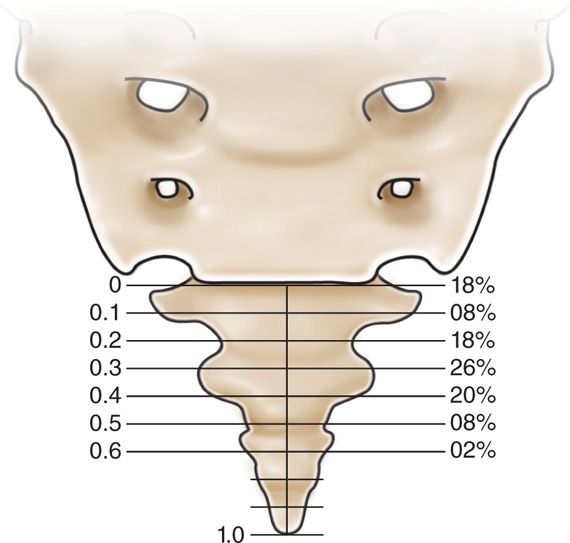

Each sympathetic trunk in the pelvic area is positioned anterior to the sacrum, situated medially to the anterior sacral foramina. There are 4 or 5 small sacral ganglia with the ganglion impar being the most caudal segment of the confluence of the sacral sympathetic chain as it passes anteromedially over the sacrum. More specifically, the ganglion Impar is the terminal fusion of the 2 sacral sympathetic chains and is located with some anatomical variability between the SCJ and the lower segment of the first coccyx. The fusion of the 2 chains typically positions the ganglion midline, which makes it relatively easy to find (Figure 49-1). However, there is a wide range of variability in the anatomical location with respect to the SCJ (Figure 49-2).5

Figure 49-1. Illustration of the ganglion Impar with relation to nearby anatomical structures on the left. The illustration on the right represents the path and trajectory of the needle through the sacrococcygeal disc at the SCJ to the ganglion impar.

Figure 49-2. Illustration of variable locations of the ganglion Impar with respect to the SCJ and the coccyx as reported by Chang-seok et al. Distances of the ganglion impar were measured using a digital caliper and a relative index was calculated. The percentages at each respective index are reported above.5

The key to successfully locating the ganglion Impar lies in identifying the following structures:

1. Sacral hiatus

2. Coccyx

3. SCJ

4. The 4 bilateral sacral foramina—for correct assessment of anteroposterior image under fluoroscopy

5. Sacral and coccygeal cornua—manually palpated to assess the surface anatomy and compared with the image

Other relevant anatomy that should be taken into consideration when performing this injection is:

1. Rectum—this is separated from the ganglion by a layer of extraperitoneal fat and connective tissue

2. Exiting nerve roots from the sacral foramen

3. Coccygeal nerve traveling within the sacral canal

4. Erector spinae muscles

5. Sacral canal

6. Lateral and posterior sacrococcygeal ligaments—that can produce resistance while advancing the needle if calcified

BASIC CONCERNS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

As with any intervention, one must weigh the potential benefits to the potential complications. In the average patient, and given the relatively less invasive nature of the technique described here, a blockade of the ganglion Impar should be considered early on in the treatment algorithm in the properly indicated patient. However, given the wide array of pathological conditions that could benefit from this injection and the associated pathophysiology, one must carefully consider each patient individually. For example, a patient suffering from radiation proctitis may have skin breakdown in the area, which might contraindicate injection.

Some basic concerns for injection are:

• Immunocompromized patients are potentially at high risk for infection, this is of particular relevance in patient with malignancy.

• Patients with metastatic cancer pain may have local masses in the region.

• Patients may have thrombocytopenia secondary to chemotherapy.

• Patients with allodynia could benefit from this injection may also have pain in the very area of the injection which could complicate the ability of one to tolerate the procedure.

• Prone position may be difficult if patient has abdominal distension.

• Possible rectal perforation may occur if the needle is advanced too far anteriorly.

Contraindications for injection include:

• Infection, systemic or localized

• Coagulopathy

• Distorted or complicated anatomy

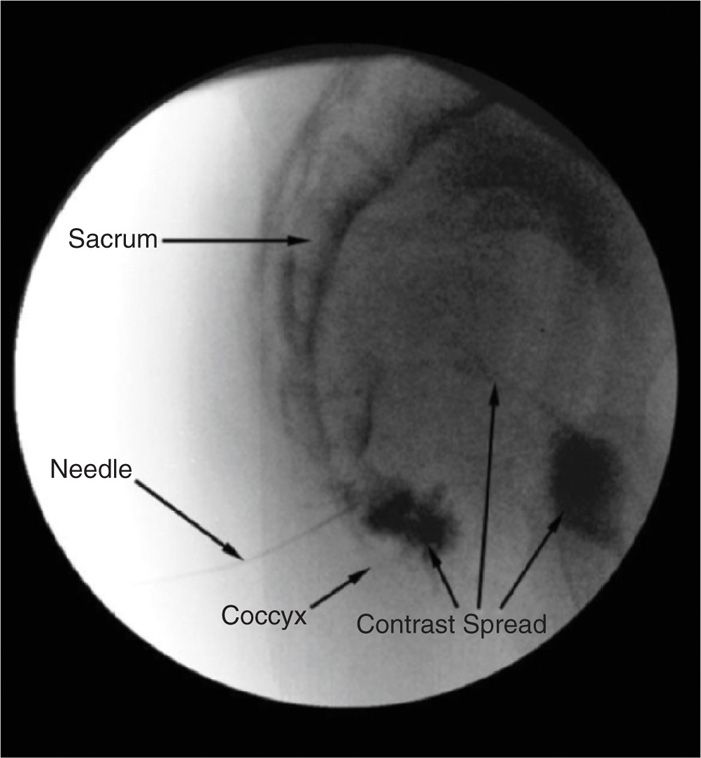

• Rectal fistula in proximity of ganglion (Figure 49-3)

Figure 49-3. Fluoroscopic image demonstrating contrast spreading through a fistula into the rectum.

• Patient refusal

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

1. Informed consent and proper explanation of all potential complications

2. Anti-coagulation—this is less of a concern than for an epidural injection but a concern nonetheless as there is inherent disruption of tissue from the introduction of a needle

3. Physical examination of the area for infection, skin ulceration or necrosis, and extent of disease

4. Patient must be able to lie prone for the intended length of the procedure.

5. Intravenous access for IV fluid and medications for sedation or hypotension if the patient experiences vasovagal reaction

6. Evaluation for contrast allergy—this is of the utmost importance as the utilization of contrast will allow for precise needle placement just anterior to the SCJ

Fluoroscopic Views

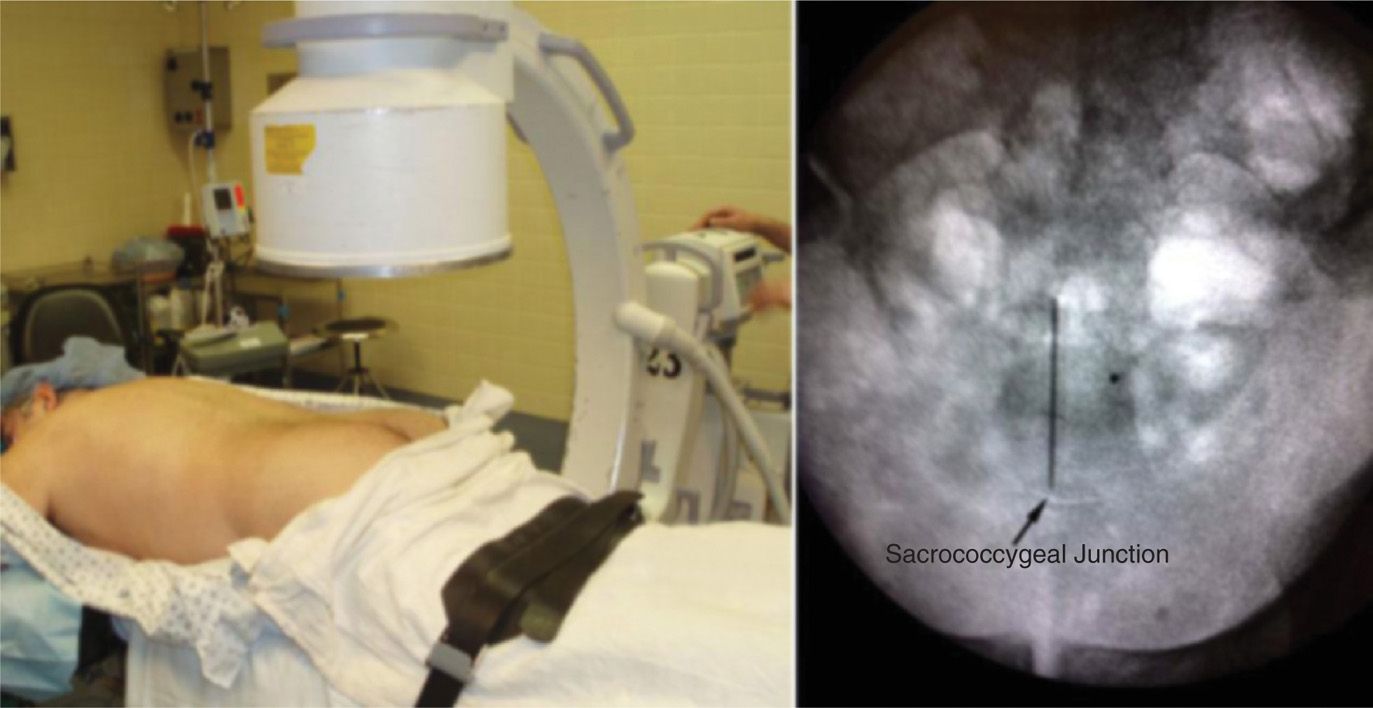

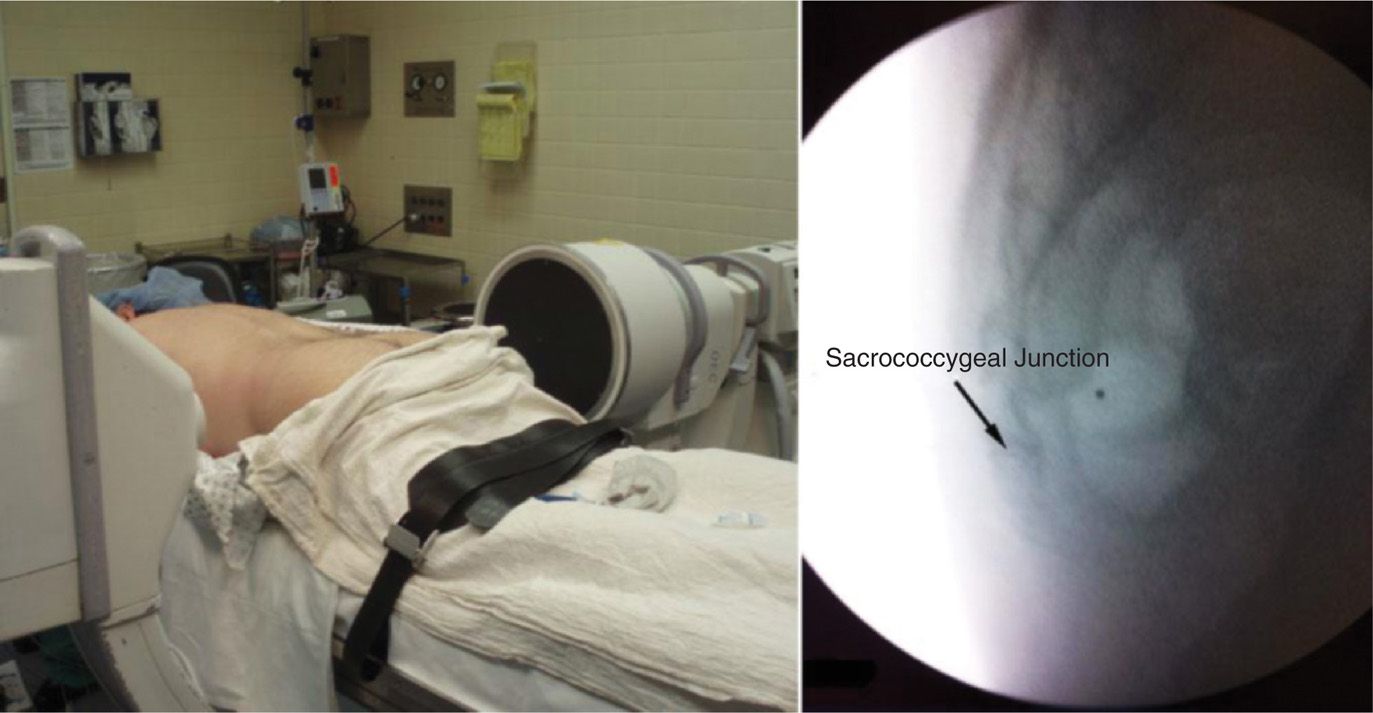

1. Start with anterior-posterior (AP) image of the sacrum with the coccyx in view. A slight caudal tilt will allow for proper visualization of the SCJ given the curvature of the sacrum and coccyx. Diligently mark the middle of SCJ to insure a midline approach, making sure the sacral foramina are equidistant from the spinous processes of the sacrum (Figure 49-4).

Figure 49-4. Image on the left demonstrates the initial positioning of the C-arm over the patient for an AP view. The image on the right is the corresponding fluoroscopic view in AP.

2. Lateral view: This is most important view. It allows the physician to control the depth of the needle tip as it advances anteriorly past the disc of the SCJ. This is also the view in which contrast will be injected to verify the position of the tip (Figure 49-5).

Figure 49-5. Image on the left demonstrates the C-arm positioned about the patient for a lateral view. The image on the right is the corresponding fluoroscopic view.

EQUIPMENT

1. 22-gauge 3.5-in spinal needle

2. 25-gauge 1.5-in needle

3. 3-cc syringe for local anesthetic

4. 5-cc syringe for contrast

5. 10-cc syringe for medications

6. Connector tubing (extension)

MEDICATIONS

1. 1% lidocaine

2. 0.25% or 0.5% bupivacaine

3. Iohexol 180 (nonionic water-soluble contrast)

4. Triamcinolone or Methylprednisolone

Technique

Varying techniques have been described for needle passage to gain access to the ganglion Impar.

• Anococcygeal approach with single-bent needle

• Anococcygeal approach with curved needle

• Trans-sacrococcygeal approach

• Coccygeal (transdiscal) joint approach

• Paramedian approach with double-bent needle

• Sub-transverse process of coccyx approach

• Needle-in-catheter technique for Cryoneurolysis

• Two needles approach for radiofrequency neurolysis

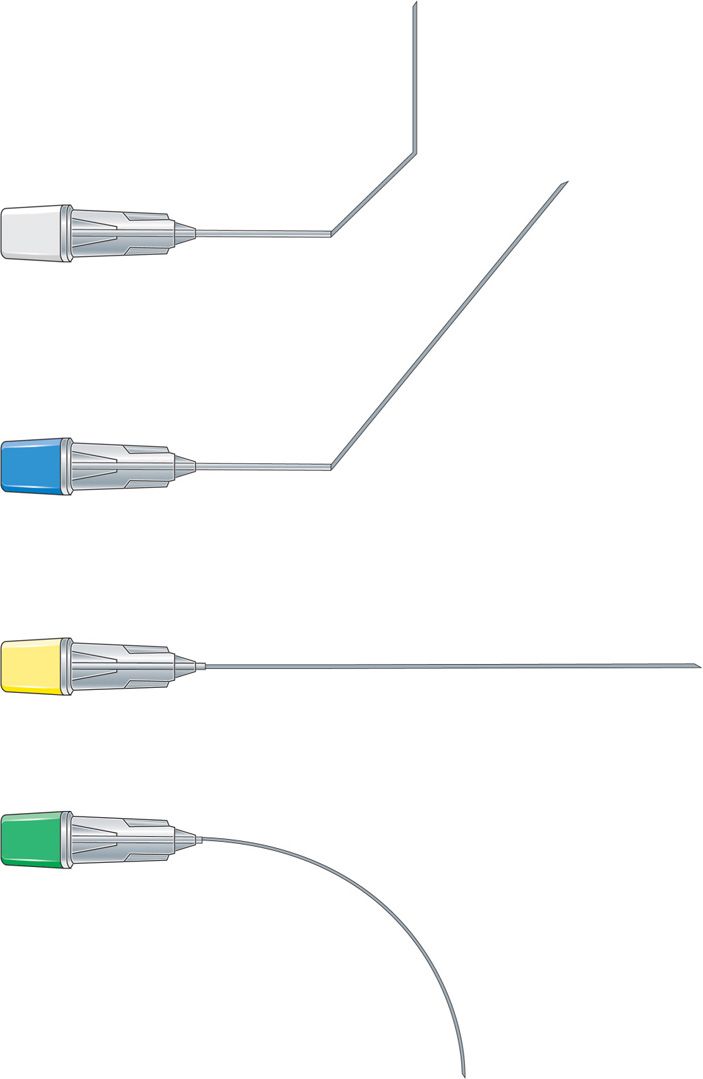

As previously mentioned, Plancarte pioneered the initial anococcygeal approach by utilizing a curved needle that makes initial contact with the skin between the anus and coccyx and directing the needle anteriorly between the coccyx and rectum.1 In using this approach, there is inherently a greater risk of contact with the rectum and often requires the physician to place a finger in the rectum to help facilitate proper needle placement. This particular technique can be uncomfortable for the patient with rectal pathology or allodynia in the area. Moreover, this approach can present a particular challenge when attempting to maintain sterility. The angulated or bent needle renders the operator unable to use the stylet, makes it more difficult to maneuver, potentially causes more tissue damage and may lead to needle breakage (Figure 49-6).

Figure 49-6. Illustration of the various configurations to a 22-gauge spinal needle for the alternative techniques described.

In an attempt to correct these predicaments, a curved needle technique6 was described which avoided some of the aforementioned problems but resulted in difficulty when attempting to pass through a calcified anococcygeal ligament; however, the overall flaws of the procedure were still the same. In the sub-transverse process approach, a curved needle is advanced just caudal to the transverse process of the coccyx.7 This results in less discomfort to the patient and allows the operator the choice of positioning the patient either prone or lateral. There is, however, still an increased risk of contact to the rectum as the curve could potentially pass too far anterior. A paramedian approach was described by McAllister et al8 where the operator uses a lateral approach using a double-bent needle to allow for better approximation to the ganglion Impar. This is difficult for patients with rectal pain as it also requires a finger to be placed in the rectum.

TRANSSACROCCYGEAL APPROACH

We advocate the most direct approach to the ganglion Impar. The transsacroccygeal approach was first described by Wemm and Saberski (Figure 49-1).9 This technique minimizes the potential risk of rectal perforation as advancing the needle is precisely controlled and monitored in the lateral view of fluoroscopy. It also circumvents the problems with altering the needle’s shape, while avoiding needle passage through the skin in close proximity to the patient’s pain complaints.

Our Preferred Technique

1. The patient is placed in a prone position with a pillow under the abdomen to reduce the lumbar lordotic curvature (Figure 49-7).

Figure 49-7. Patient positioned in the prone position with pillow under the abdomen.

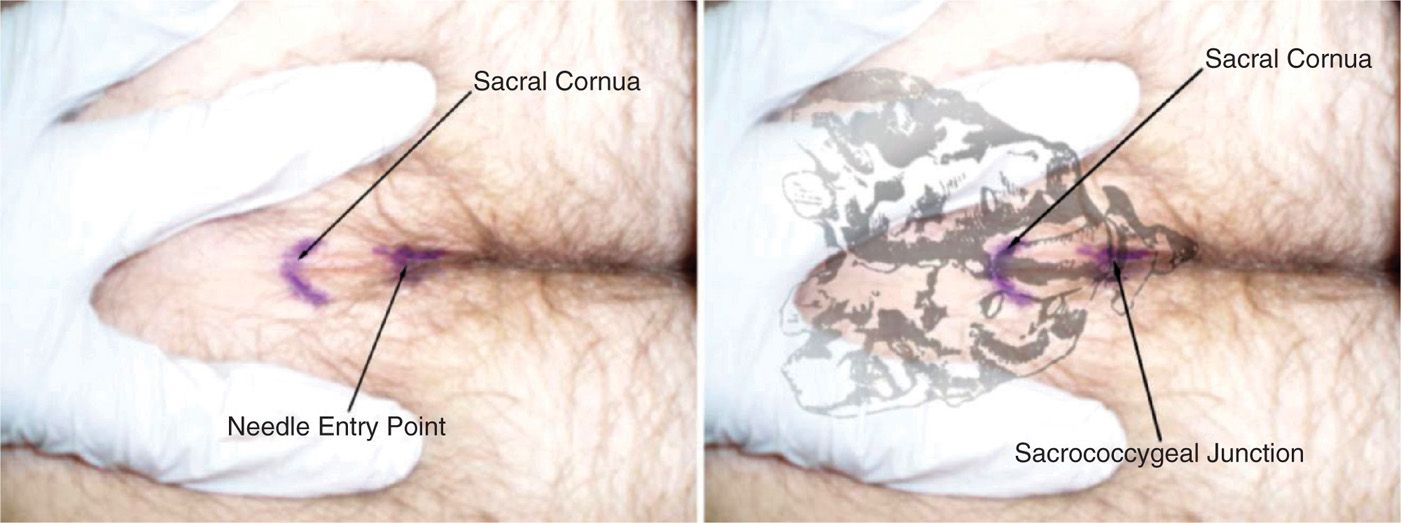

2. The skin overlying the SCJ is identified with an AP fluoroscopic image, marked and prepared in a typical sterile fashion (Figures 49-4 and 49-8).

Figure 49-8. Image on the left shows the skin marked for injection. Image on the right demonstrates a representation of the underlying bony anatomy.

3. 1% lidocaine is then used to infiltrate the skin overlying the SCJ using the 25-gauge 1.5-in needle to provide adequate skin analgesia.

4. Contrast is drawn up into the 5-cc syringe with the connector tubing attached and primed.

5. Injectate is drawn up in the 10-cc syringe which consists of 40-mg of either triamcinolone or methylprednisolone and 4-cc of 0.25% bupivacaine. Total 5-cc volume of injectate is recommended to cover the area of the elongated ganglion Impar.

6. The 22-gauge 3.5-in spinal needle is then advanced anteriorly through sacrococcygeal joint under fluoroscopic guidance into the most midline aspect.

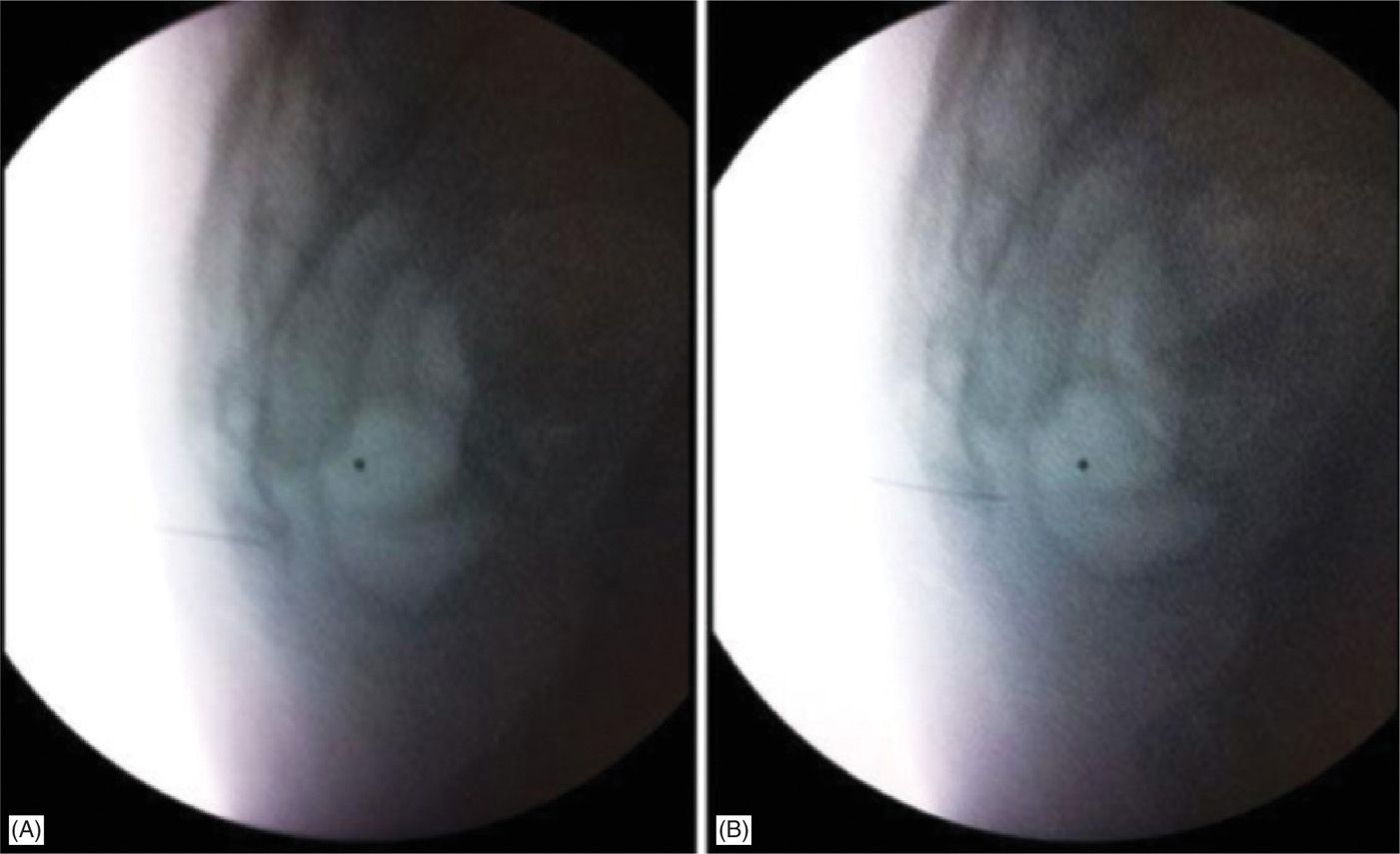

7. Once the needle is suspected to have contacted the SCJ, the fluoroscopic view changed to lateral (Figure 49-5) to monitor the depth of the needle tip into the SCJ (Figure 49-9a).

Figure 49-9. (A) Image on the left is a lateral fluoroscopic view of the needle with the tip lying in the SCJ. (B) Image on the right is a lateral fluoroscopic image of the needle as the tip has passed just anterior to the SCJ and now lying in the retroperitoneal space.

8. The needle is then carefully advanced 1 millimeter at a time until the tip passes just anterior to the disc of the SCJ—this can be felt as a “loss of resistance” if the local anesthetic syringe is kept on the needle (Figure 49-9b).

9. Once the needle is suspected to be just anterior to the SCJ, the syringe containing contrast is attached to the spinal needle via the connector.

10. The needle is then aspirated to ensure that the needle is not intravascular.

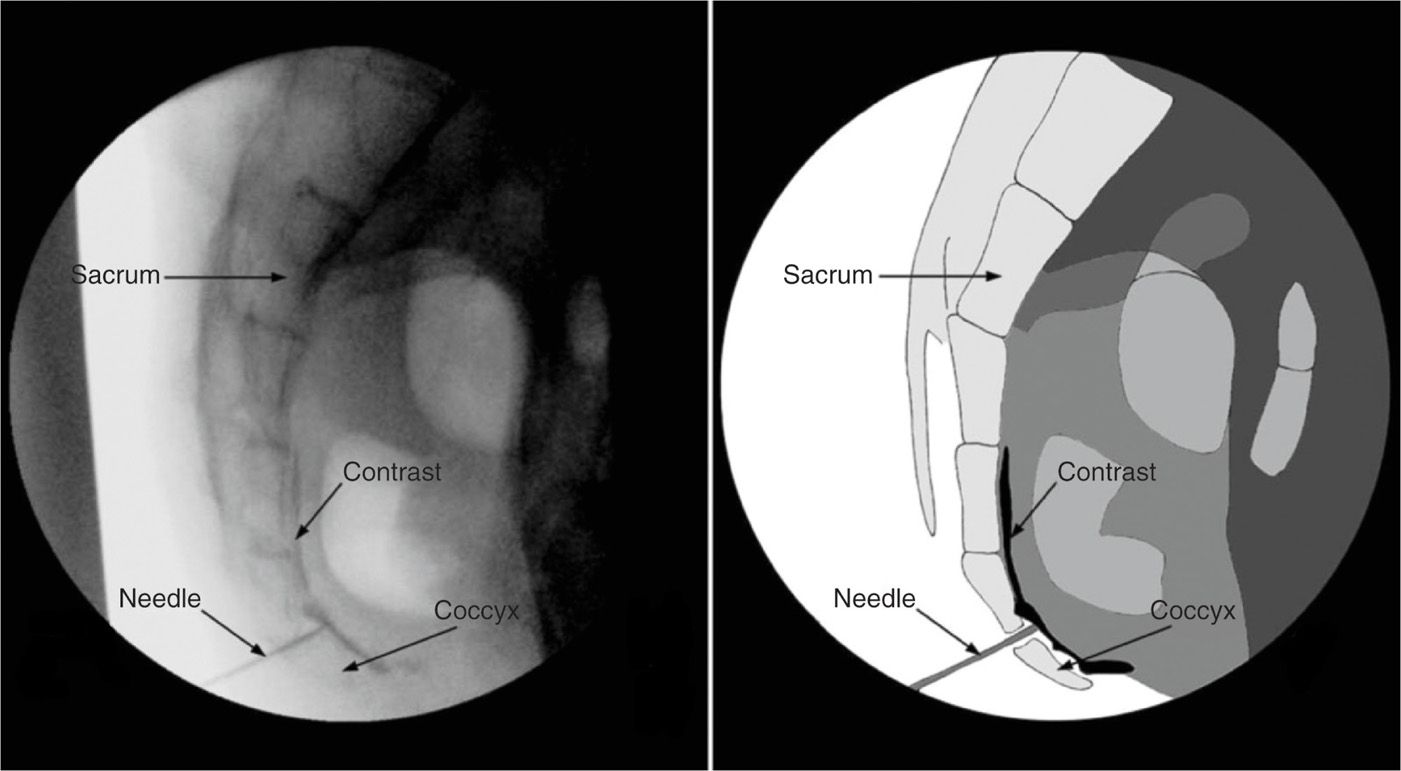

11. Contrast is injected under live-fluoroscopy into the retroperitoneal space and the spread of the dye should give a “reverse comma” appearance when seen on the lateral view (Figure 49-10).

Figure 49-10. Lateral fluoroscopic image (left) with the needle tip just anterior to the SCJ in the retrorectal space (between the sacrum and the rectum) and contrast spread in the “reverse coma” appearance. The image on the right is an illustration of the fluoroscopic image.

12. Careful examination should be made to ensure there is no unintended contrast spread—within the SCJ itself, intravascular, or outside the space containing the ganglion Impar.

13. Once proper placement has been ensured, the 5-cc syringe is removed and 10-cc syringe containing the injectate is attached to the tubing.

14. The injectate is then injected slowly.

15. The needle is then flushed and withdrawn.

16. Sterile dressing is applied.

If additional control is desired, as well as extra assurance to avoid needle fracture, one can use a “needle-inside-needle” approach.

1. The technique described by Munir et al12 utilizes a 22-gauge 1.5-in needle inserted over the sacrococcygeal disc at the superior aspect of the intergluteal crease, just below the sacral hiatus.

2. The needle is then advanced under lateral fluoroscopic imaging until the tip is through the disc.

3. Then a 25-gauge 2-in spinal needle is introduced through the 22-guage introducer—the remaining steps are the same as those described above.

If the patient receives excellent but only temporary relief, the same procedure can be repeated using 1% lidocaine followed by 6% phenol in glycerin for neurolysis.

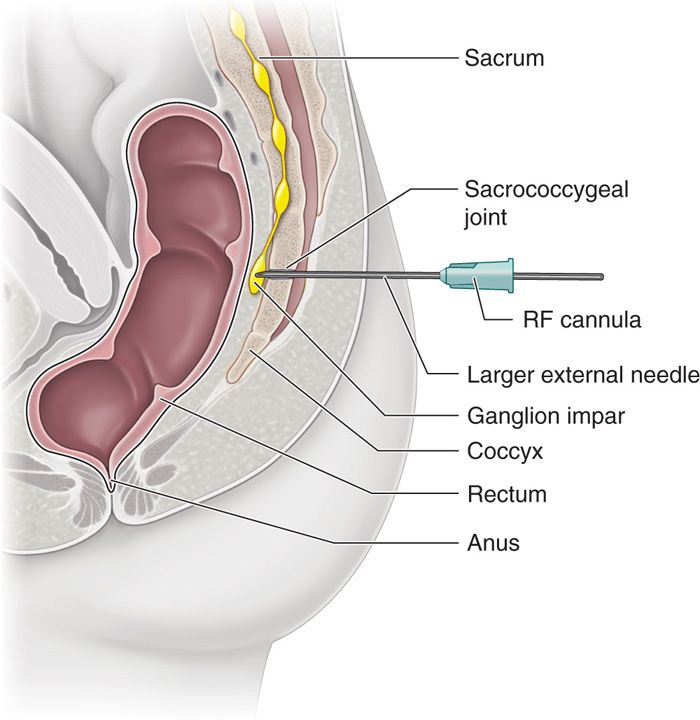

NEEDLE-IN-NEEDLE TECHNIQUE FOR RF

This technique is used for radiofrequency neurolysis of the ganglion Impar. The Teflon coating of an RF cannula can be damaged while advancing through the often calcified sacrococcygeal joint. The tougher, larger 22-gauge needle is introduced first, and then RF cannula is passed through the first needle to place it anterior to the SCJ (Figure 49-11).

Figure 49-11. Needle-in-needle technique. A sturdy larger needle is used to enter the sacrococcygeal joint to minimize the damage to Teflon coating of the radiofrequency cannula.

Post-Procedure Follow-Up

The patient should be followed up by telephone the next day for the potential complications and queried regarding immediate pain relief secondary to the local anesthetic effect. The anti-inflammatory effect of the steroid will not be apparent for several days. The patient should be advised to call the pain service for any procedure-related complications and/or any unexpected neurological deficit. Patient should be monitored closely for following:

2. Urinary or bowel incontinence

3. Fever

4. Bleeding

5. Rectal bleeding

6. Numbness

7. Exacerbation of symptoms

Potential Complications and Pitfalls

While the transsacroccygeal offers the operator a more straightforward approach and considerably limits the potential complications compared to a lateral approach with angled or curved needle, there are still obstacles that could be encountered. This approach can be challenging in those patients with a history of coccygectomy, arthritis of SCJ, or calcification of the tissue between the sacrum and coccyx.4 This can be of particular concern in the elderly and those exposed to radiation treatment to the area. Other potential complications are:

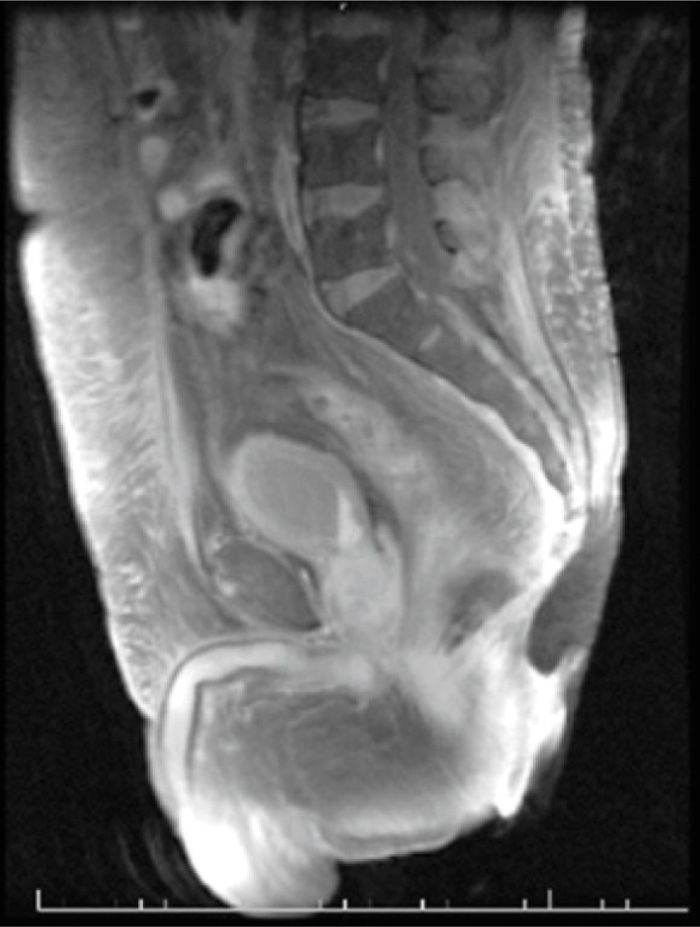

1. Infection (Figure 49-12)

Figure 49-12. Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI) of a patient with coccygeal osteomyelitis.

2. Bleeding

3. Rectal perforation

4. Neurolytic injection into nerve roots or rectal cavity

5. Cauda Equina Syndrome

6. Nerve root injection (Neuritis)

7. Intravascular injection

8. Osteitis or periostitis

9. Sacrococcygeal discitis

10. Hematoma

11. Inadvertent spread may potentially lead to motor, sexual, or bowel/bladder dysfunction

Clinical Pearls

1. These injections can be diagnostic as well as therapeutic. The patients with positive diagnostic injections are generally candidates for radiofrequency (RF) ablation, cryoneurolysis, or neurolysis by phenol or alcohol.

2. The success of this procedure is most dependent on the exact location of the ganglion Impar relative to the SCJ. As mentioned above, there is anatomical variability of the location of the ganglion, which can create variable results.

3. Patients can expect anywhere from 50% to 100% pain relief.1,10,11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree