INTRODUCTION

NORMAL FUNDUS

The disk is pale pink, approximately 1.5 mm in diameter, with sharp, flat margins. The physiologic cup is located within the disk and usually measures less than six-tenths the disk diameter. The cups should be approximately equal in both eyes.

The central retinal artery and central retinal vein travel within the optic nerve, branching near the surface into the inferior and superior branches of arterioles and venules, respectively. Normally the walls of the vessels are not visible; the column of blood within the walls is visualized. The venules are seen as branching, dark red lines. The arterioles are seen as bright red branching lines, approximately two-thirds or three-fourths the diameter of the venules.

This is an area of the retina located temporal to the disk; it is void of visible vessels. The fovea is an area of depression approximately 1.5 mm in diameter (similar to the optic disk) in the center of the macula. The foveola is a tiny pit located in the center of the fovea. These areas correspond to central vision.

The background fundus is red; there is some variation in the color, depending on the amount of individual pigmentation and the visibility of the choroidal vessels beneath the retina.

Fundal examination should be an integral part of any eye examination.

The cup/disk ratio is slightly larger in the African American population.

The normal fundus should be void of any hemorrhages, exudates, or tortuous vasculature.

FIGURE 3.1

Normal Fundus. The disk has sharp margins and is normal in color, with a small central cup. Arterioles and venules have normal color, sheen, and course. Background is in normal color. The macula is enclosed by arching temporal vessels. The fovea is located by a central pit. (Photo contributor: Jeffrey Goshe, MD.)

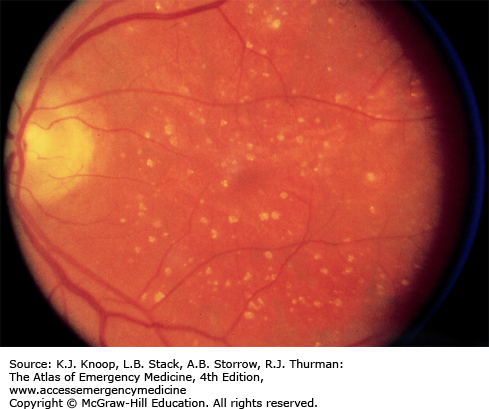

AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION

Age-related macular degeneration increases in incidence with each decade over 50 and is evidenced by accumulation of either hard drusen (small, discrete, round, punctate nodules) or soft drusen (larger, pale yellow or gray, without discrete margins that may be confluent). Most patients with drusen have good vision, although there may be decreased visual acuity and distortion of vision. There may be associated pigmentary changes and atrophy of the retina. Vision may slowly deteriorate if atrophy occurs.

Patients with early or late degenerative changes of the macula are at risk of developing choroidal neovascularization (CNV), which is associated with distortion of vision, blind spots, and decreased visual acuity. Macular appearance may show dirty gray lesions, hemorrhage, retinal elevation, and exudation.

Patients with drusen need ophthalmologic evaluation every 6 to 12 months or sooner if visual distortion or decreasing visual acuity develops. If a patient complains of deterioration of visual acuity or image distortion, prompt ophthalmic evaluation is warranted.

Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness in the United States in patients above 65 years of age.

Patient may have normal peripheral vision.

Untreated CNV can lead to visual loss within a few days.

Patients frequently complain of distortion with CNV.

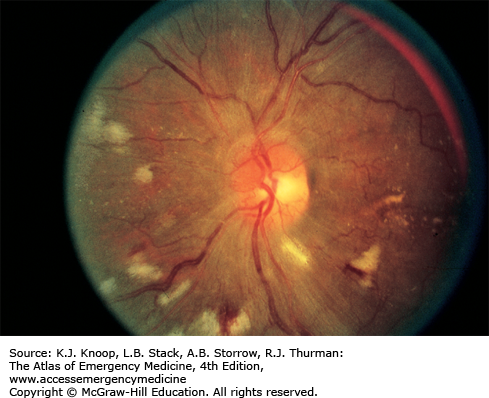

EXUDATE

Hard exudates are refractile, yellowish deposits with sharp margins composed of fat-laden macrophages and serum lipids. Occasionally the lipid deposits form a partial or complete ring (called a circinate ring) around the leaking area of pathology. If the lipid leakage is located near the fovea, a spoke or star-type distribution of the hard exudates may be seen.

Cotton wool spots, or soft “exudates,” are actually microinfarctions of the retinal nerve fiber layer, and appear white with soft or fuzzy edges.

Inflammatory exudates are secondary to retinal or chorioretinal inflammation.

Hard exudation and cotton wool spots are associated with vascular diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and collagen vascular diseases but can be seen with papilledema and other intrinsic ocular conditions. Inflammatory exudates are seen in patients with such diseases as sarcoidosis and toxoplasmosis.

Routine referral for ophthalmologic and medical workup is appropriate.

Hard exudates that are intraretinal may easily be confused with drusen occurring near Bruch membrane, which separates the retina from the choroid.

FIGURE 3.6

Cotton Wool Spots. White lesions with fuzzy margins, seen here approximately one-fifth to one-fourth disk diameter in size. Orientation of cotton wool spots generally follows the curvilinear arrangement of the nerve fiber layer. Intraretinal hemorrhages and intraretinal vascular abnormalities are also present. (Photo contributor: Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

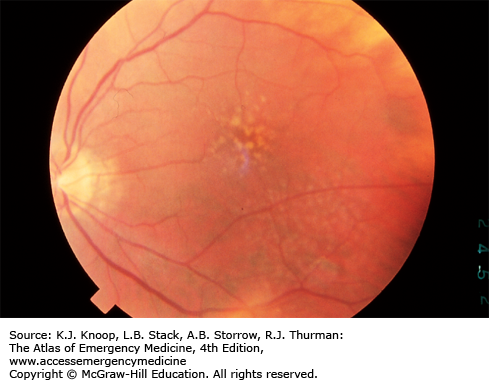

ROTH SPOTS

Roth spots are retinal hemorrhages with a white or yellow center. They may be seen in patients with a host of diseases such as anemia, leukemia, multiple myeloma, diabetes mellitus, collagen vascular disease, other vascular diseases, intracranial hemorrhage in infants, septic retinitis, and carcinoma. Flame-shaped or splinter hemorrhages or dot-blot hemorrhages may resemble Roth spots.

Routine referral for general medical evaluation is appropriate.

Roth spots are not pathognomonic for any particular disease process and can represent a variety of clinical conditions.

These lesions represent red blood cells surrounding inflammatory cells.

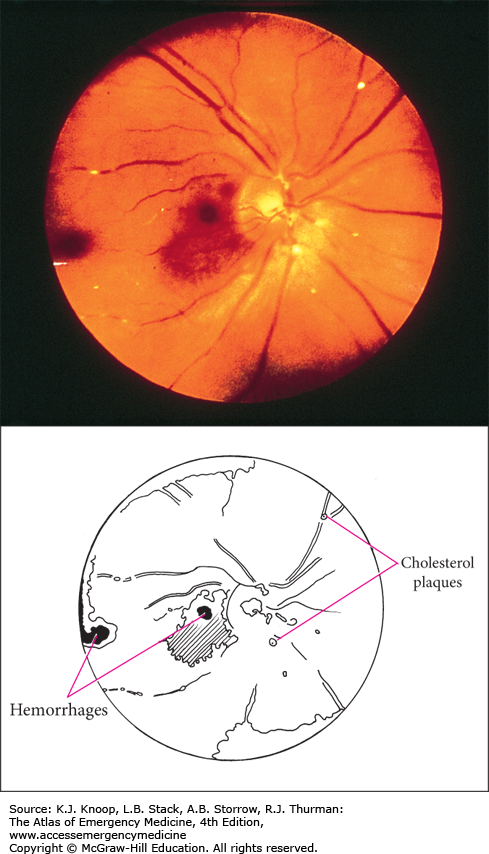

EMBOLI

Plaques, if present, are often found at arteriolar bifurcations. Patients may have signs and symptoms of vascular disease such as carotid bruits or stenosis, aortic stenosis, aneurysms, or atrial fibrillation. Amaurosis fugax, a transient loss of vision often described as a curtain of darkness obscuring vision with sight restoration within a few minutes, may be present in the history.

Cholesterol emboli (Hollenhorst plaques), associated with generalized atherosclerosis, often from carotid atheroma, are bright, highly refractile plaques. Platelet emboli (carotid artery or cardiac thrombus) are white and very difficult to visualize. Calcific emboli (cardiac valvular disease) are irregular and white or dull gray and much less refractile.

Referral for routine general medical evaluation is appropriate unless the patient presents with signs or symptoms consistent with showering of emboli, transient ischemic attack, or cerebrovascular accident, in which case admission should be considered.

Retinal emboli may produce a loss of vision, either transient or permanent in nature.

Arteriolar occlusion may occur in either a central or a peripheral branch location.

Occurrence of retinal emboli should prompt the clinician to search for an embolic source as the event may be a precursor to impending ischemic stroke.

CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

In central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), the typical patient experiences a sudden painless monocular loss of vision, either segmental or complete. Visual acuity may range from finger counting or light perception to complete blindness. Fundal findings may include the following: fundal paleness caused by retinal edema; the fovea does not have the edema and thus appears as a cherry-red spot; narrow and irregular retinal arterioles; and a “boxcar” appearance of the retinal venules.

Attempts to restore retinal blood flow may be beneficial if performed in a very narrow time window after the acute event. This may be accomplished by (1) decreasing intraocular pressure (IOP) with topical β-blocker eye drops or intravenous acetazolamide; (2) ocular massage, applied with cyclic pressure on the globe for 10 seconds, followed by release and then repeated. Urgent consultation with an ophthalmologist is indicated to determine if more aggressive acute therapy (paracentesis) is warranted. However, such aggressive treatment rarely alters the poor prognosis. Medical evaluation and treatment of associated findings may be warranted. Tissue plasminogen activator may be considered for lysis of an occluding thrombus.

Visual decrement may be caused by a “low-flow” state (vs total occlusion). As this cannot be identified on presentation and can present hours later, immediate treatment and consultation is indicated regardless of the time of onset.

Sudden, painless monocular vision loss is typical.

CRAO may be associated with temporal arteritis. This diagnosis should be strongly considered in all patients presenting with signs and symptoms of CRAO who are older than 55 years.