INTRODUCTION

Foot injuries occur most commonly in work and athletic environments.1 Work-related foot injuries can be associated with substantial medical costs and lost wages.2 Sport-related foot and ankle injuries require care so the athlete can return to the demands of the sport as quickly as possible.3 Motor vehicle crash patients with a foot or ankle injury typically have a higher injury severity score than those without such injuries.4

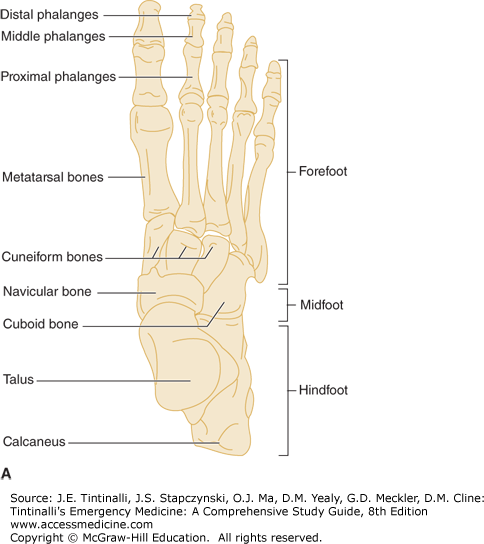

The foot is divided into three sections: the hindfoot, the midfoot, and the forefoot. The Chopart joint separates the hindfoot from the midfoot. The Lisfranc joint divides the midfoot and the forefoot. The hindfoot is comprised of the talus and the calcaneus. The midfoot encompasses the medial, middle, and lateral cuneiforms; the navicular; and the cuboid. The tarsus refers to the bones of the hind and midfoot. The forefoot includes the metatarsals and the proximal, middle, and distal phalanges (Figure 277-1). Ligaments and muscles enable foot movements of eversion, inversion, adduction, and abduction.

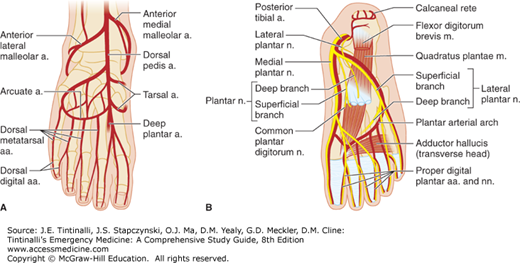

Vascular supply of the foot originates from branches of the popliteal artery: the anterior tibial artery, with its branch the dorsalis pedis supplying the dorsal aspect of the foot; and the posterior tibial and peroneal arteries supplying the sole (Figure 277-2).

FIGURE 277-2.

A. Arteries of the dorsum of the foot. B. Vessels and nerves of the sole of the foot. a. = artery; aa. = arteries; Abd. hall. = abductor hallucis; Ant. lat. = anterior lateral; Ant. med. = anterior medial; br. = branch; brev. = brevis; dig. = digitorum; Flex. = flexor; Lat. = lateral; Med. plant. = medial plantar; n. = nerve; nn. = nerves; Post. = posterior; Quad. = quadratus; Superf. = superficial; trans. = transverse.

The sural, saphenous, peroneal, and lateral plantar nerves innervate the foot for both motor and sensory function and originate in branches from the sciatic and femoral nerves.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Ask about the mechanism of injury and direction of force. Obtain key information, including ability to bear weight after the injury, prior injury or surgery to the area, and any other potential injuries. Because it requires great force to fracture the foot, other injuries can coexist, and foot pain can distract from other serious injuries.

The foot examination does not necessarily begin with the foot, but with the entire lower extremity on the affected side. Examine the hip, knee, and ankle. Evaluate neurovascular integrity. Vascular compromise of the foot is identified with diminished pulses, a cool extremity, and mottled skin. Once the general examination is completed and the focused foot examination begins, start with the general appearance of the foot and compare it with the uninjured side. Look for obvious closed or open deformities. Ask the patient to identify painful areas. Palpate the foot for abnormal findings or tenderness. Pay particular attention to the base of the fifth metatarsal and the dorsal aspect of the base of the second metatarsal. Range the joint both passively and actively through all typical motions of the foot. Evaluate gait when possible.

HINDFOOT INJURIES

The calcaneus is the most commonly fractured tarsal bone, whereas the talus is infrequently fractured.5 Fractures in the hindfoot typically require a large force, like an axial load to the heel, to occur. Because of this force, associated injuries are common.

Calcaneal fractures are subdivided into intra-articular and extra-articular fractures, with intra-articular fractures being the more common of the two. A displaced intra-articular fracture is common and poses its own challenges for long-term care. Some surgeons advocate for open reduction and internal fixation; others prefer nonoperative closed reduction; and still others prefer primary arthrodesis.6

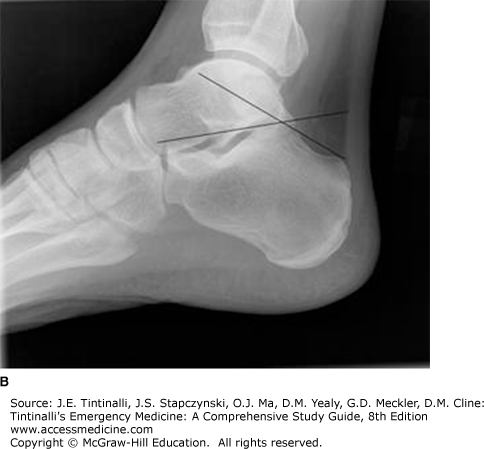

Plain radiographs, specifically the lateral view, are needed for fracture diagnosis. The Boehler angle is measured using the lateral view and represents the intersection of two lines: (1) the line drawn from the highest part of the anterior process of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior articular surface of this bone, and (2) the line between the highest point of the posterior articular surface of the calcaneus and the most superior part of the calcaneal tuberosity. The normal angle measures between 25 and 40 degrees. When the angle is <25 degrees, suspect a fracture (Figure 277-3). Because this angle varies widely between individuals, a comparison view is helpful if the diagnosis is in question. Although plain radiographs are helpful when the fracture is visible, a CT can provide detail and help clarify the management plan.

For intra-articular fractures, obtain orthopedic consultation to determine the management plan. For nondisplaced fractures, treat an intra-articular fracture with immobilization, a well-padded posterior splint, strict elevation, non–weight-bearing status, and appropriate analgesia. Elevate the leg above the heart to minimize edema and the risk of compartment syndrome (see the chapter titled “Compartment Syndrome”). Displaced fractures may require surgical repair. Care for an extra-articular fracture is elevation, immobilization, analgesia, and orthopedic follow-up. Some of these will require outpatient surgical intervention, with less invasive, percutaneous approaches being adopted in more recent years.7

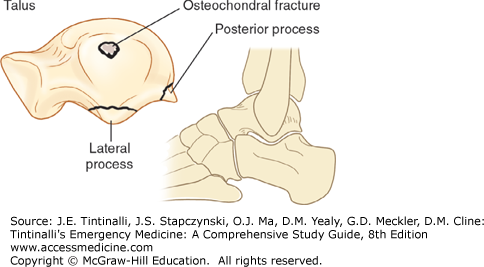

Fractures of the talus usually require a significant mechanism such as extreme dorsiflexion or a fall from a great height. “Major” talus fractures are those involving the head, neck, or body of the talus (Figure 277-4) and can result in avascular necrosis. “Minor” talus fractures are those that do not cross the central part of the talus (Figure 277-5). A lateral process talar fracture is sometimes called “snowboarder’s ankle,” and is commonly mistaken for a lateral ankle sprain.

Diagnosis begins with plain radiography, but CT provides better visualization of the talus. Minor talus fractures can be treated on an outpatient basis with a posterior splint, non–weight-bearing status, analgesia, and orthopedic referral. Major talar fractures ideally require orthopedic consultation in the ED.

Dislocations of the talus, when the tibiotalar joint remains intact, are either peritalar or subtalar. The talocalcaneal and talonavicular joints are disrupted by a rotational-inversion force. Dislocations are rare but are orthopedic emergencies. Immediate orthopedic consultation and reduction are necessary to prevent neurovascular compromise to the foot.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree