Key Clinical Questions

What mechanisms cause cutaneous flushing?

How does one differentiate benign and malignant etiologies of flushing?

What tests and studies are useful to evaluate each potential diagnosis?

What treatments are available for each etiology?

What is the difference between acute and chronic urticaria?

What are the common causes of acute urticaria and chronic urticaria?

What is the appropriate workup for patients with acute or chronic urticaria?

In what clinical scenario is a skin biopsy indicated?

What is the appropriate workup when vasculitis is present on skin histology?

What therapies are available for acute and chronic urticaria?

Flushing: Clinical Manifestations and Causes

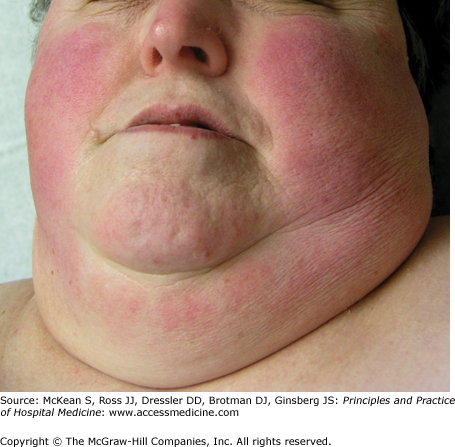

Flushing results from vasodilation in the skin, produced by release of vasoactive mediators or activity of the vasomotor nerves. It is characterized by sudden warmth and visible erythema, affecting the head (Figure 141-1), neck, and upper chest, regions of abundant superficial cutaneous vasculature. Flushing may be episodic or constant. When persistent, it may produce fixed facial erythema with a cyanotic tinge, secondary to the development of telangiectasias and large cutaneous blood vessels, containing slow-moving, deoxygenated blood (Figure 141-2).

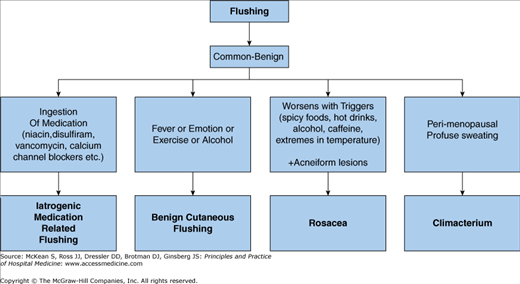

The overwhelming majority of patients with flushing have common and relatively innocuous causes, with only a small proportion of cases being associated with tumors and other significant underlying medical problems (Table 141-1).

|

Flushing is most often physiologic (benign cutaneous flushing). It is more common in women than men. Common precipitants include fever, exercise, warm temperatures, spicy foods, and alcohol. In fair-skinned persons, flushing (or blushing) often occurs in response to strong emotion, which perhaps evolved as a nonverbal means to express arousal or display vigor. Although blushing historically was thought attractive, it may produce anxiety and distress in some contemporary patients.

Rosacea is characterized by acneiform inflammation of the central face, with erythema, flushing episodes, telangiectasias, and often papules and pustules. Eye lesions, such as blepharitis, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and keratitis with corneal ulcers also occur. It is common in fair-skinned patients of middle age; the prevalence among Caucasian women in the United States is approximately 16%. The etiology is unknown. There seems to be a genetic predisposition. Helicobacter pylori and the face mite Demodex folliculorum have been invoked as possible causes, with equivocal data. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have also been suggested to play a role. These peptides, such as cathelicidins and beta-defensins, are components of the innate immune system, with broad antimicrobial activity. They are released with any injury to the skin. LL-37 canthelicidin is expressed in abnormally high amounts in the skin of rosacea patients, compared to controls. When LL-37 has been injected into the skin of mice, the mice demonstrate a phenotype similar to rosacea patients, with erythema, inflammation and telangiectasias. Rosacea must be distinguished from systemic lupus erythematosus and photosensitivity eruptions. Rosacea is confined to the face; extrafacial lesions suggest another etiology.

Climacteric flushing occurs in 50% to 85% of menopausal women not taking estrogen replacement. It may be experienced as a wave of heat radiating outward from the upper body, and typically lasting 3 to 4 minutes. Skin temperature is elevated about 1°C during hot flashes, and heart rate also rises. The physiology is poorly understood, but may relate to changes in hypothalamic thermoregulation associated with fluctuations in estrogen levels. Episodes are often associated with the same precipitants as benign physiologic flushing, but they may also be unprovoked. If frequent, concentration and sleep may be disturbed, and depression and fatigue may result. Lifestyle measures, including keeping the body cool and avoiding triggers, may be helpful. Estrogen replacement is the most effective drug therapy, but should only be prescribed after a detailed discussion of risks and benefits.

All vasodilator drugs, such as nitroglycerine, sildenafil, and calcium channel blockers, may lead to flushing. Niacin-induced flushing is due to the subcutaneous release of prostaglandin D2, along with the formation of vasodilatory prostanoids. Morphine and other opiates may trigger histamine release from mast cells, leading to flushing. Sulfonylurea drugs interfere with the metabolism of alcohol, leading to acetaldehyde-related flushing when these patients imbibe alcohol.

Alcohol and its metabolite acetaldehyde are both vasodilators and may lead to flushing. Wines may contain several substances which provoke flushing, including tyramine, histamine, and sulfites. Asian populations have a prevalence rate of alcohol-related facial flushing of up to 36%, often related to an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, which leads to a buildup of acetaldehyde. Spicy foods and foods containing tyramine (aged cheeses and meats, soy products), sulfites (wines, dried fruits), or nitrites (cured meats) may lead to flushing. Flushing from scombroid poisoning (histamine fish poisoning) results from eating fish which has been left at room temperature too long, leading to conversion of histidine to histamine by surface bacteria. It is not a true allergy.

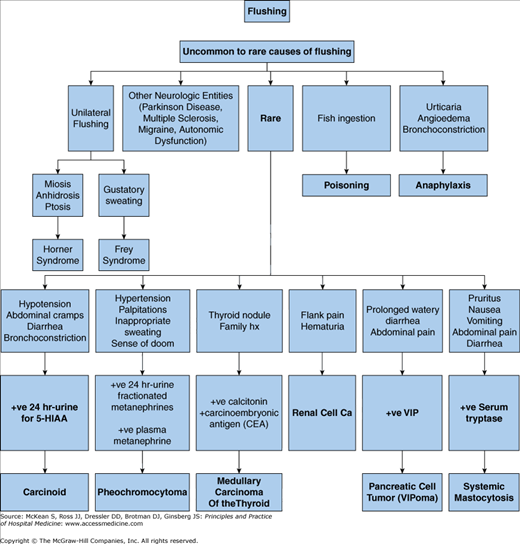

An uncommon cause of flushing, carcinoid tumors are, in general, quite rare and occur in approximately 2 per 100,000 people. Carcinoid syndrome occurs in about 10% of patients with carcinoid tumors. Carcinoid syndrome (CS) occurs in approximately 10% of all patients with carcinoid tumors. Flushing is the most frequent clinical sign, appearing in up to 95% of patients at some point during the course of their disease. The likelihood of flushing in carcinoid syndrome is dependent on the production of tumor-derived mediators such as 5-hydroxytryptamine and substance P and on the anatomic location of the carcinoid tumor. The flushing associated with CS is distinctive, occurring as well-defined, intensely pruritic reddish-brown wheals all over the body, including the palms and soles.

The annual incidence of pheochromocytoma in the United States is estimated to be approximately 500 to 1100 cases per year. Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland, another uncommon malignancy associated with flushing, is a tumor of the parafollicular, or C cells, of the thyroid gland and accounts for approximately 5% to 8% of all thyroid tumors. Pancreatic VIPoma, a neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreatic islet cells, is associated with watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and flushing. VIPoma occurs at a rate of approximately 0.05 to 0.2 new cases per million adults.

Systemic mastocytosis is a condition that presents with increased mast cells in the skin and visceral organs. When the mast cells degranulate, they release many mediators including histamine, which as discussed above, is believed to cause flushing through its vasodilatory effect on vascular smooth muscle.

Malignant causes, such as pheochromocytoma produce flushing by the elevated production of endogenous catecholamines. These substances are well-described mediators of flushing when administered exogenously.

Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland produces calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The flushing associated with this entity is believed to be due to the overproduction of these products, especially calcitonin. Flushing, and diarrhea, can sometimes be the presenting symptoms of medullary thyroid cancer.

Pancreatic islet cell tumors are neuroendocrine tumors of the gut and include insulinoma, gastrinoma, glucagonoma, somatostatinoma and VIPoma. VIPoma, a tumor of the delta cells of the pancreas, specifically produces increased amounts of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). VIP relaxes vascular smooth muscle which produces the cutaneous flush associated with this tumor.

An uncommon but potentially life-threatening cause of flushing is anaphylaxis. Acute anaphylaxis is mediated by the massive release of histamine and prostaglandin D2, as well as tryptase, to a lesser degree. It is felt that both histamine and prostaglandin D2, through its vasodilatory activity on vascular smooth muscle produces the cutaneous manifestation of flushing.

Neurologic disorders that may affect the autonomic nervous system, such as Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, and migraine, may occasionally lead to flushing. Cluster headache and paroxysmal hemicrania may cause ipsilateral facial pain and autonomic disturbances, including flushing. Patients with Horner syndrome may have ipsilateral ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis, and loss of flushing. Flushing is preserved on the contralateral side, leading to asymmetric physiologic flushing (“harlequin syndrome”). The patient may erroneously perceive the contralateral flushing as the abnormality. Causes of Horner syndrome include Pancoast tumors of the lung, carotid aneurysm, brainstem stroke, and multiple sclerosis. Aberrant nerve regeneration after parotid gland injury or surgery may result in ipsilateral flushing and sweating with eating and salivation (Frey syndrome).

Diagnosis

Once you have identified the patient’s complaint as consistent with flushing, it is necessary to evaluate for the underlying etiology. While episodic flushing can be a normal physiologic response to external factors such as heat or alcohol, persistent flushing is uncommon and should raise a red flag to the clinician that further investigation is warranted. Consideration of associated signs and symptoms may help to guide your decision making (Figures 141-3 and 141-4).

If the patient’s flushing is triggered by spicy foods, hot drinks, alcohol, caffeine, and extremes in temperature, you should consider the diagnosis of rosacea. The diagnosis is made on clinical findings, as there is no specific confirmatory laboratory testing. Rosacea can be a condition that not only involves the skin, but can also have ocular symptoms; therefore, the patient should preferably be evaluated by a dermatologist and an ophthalmologist.