FACIAL TRAUMA

PAUL L. ARONSON, MD AND MARK I. NEUMAN, MD, MPH

RELATED CHAPTERS

Resuscitation and Stabilization

Signs and Symptoms

Trauma

Surgical Emergencies

• Ophthalmic Emergencies: Chapter 131

Procedures and Appendices

KEY POINTS

Stabilization of the airway is the primary concern among children with facial trauma.

Stabilization of the airway is the primary concern among children with facial trauma.

Computerized tomography is the optimal imaging study for suspected facial fractures.

Computerized tomography is the optimal imaging study for suspected facial fractures.

Prompt recognition of extraocular muscle entrapment associated with orbital floor fractures is critical to prevent muscle ischemia and fibrosis.

Prompt recognition of extraocular muscle entrapment associated with orbital floor fractures is critical to prevent muscle ischemia and fibrosis.

Displaced nasal bone fractures should be repaired within 7 days of injury.

Displaced nasal bone fractures should be repaired within 7 days of injury.

Fast-absorbing plain gut sutures have demonstrated similar cosmetic performance to nonabsorbable sutures for the repair of facial lacerations.

Fast-absorbing plain gut sutures have demonstrated similar cosmetic performance to nonabsorbable sutures for the repair of facial lacerations.

GOALS OF EMERGENCY THERAPY

Stabilization of the Airway

While injuries sustained as a result of facial trauma are rarely life-threatening, patients who have sustained enough force to cause significant facial injury may have other associated serious injuries. Stabilization of the airway is therefore the primary concern in the management of facial injuries in children. Airway obstruction may result from blood in the mouth, loose teeth, and pharyngeal edema. Thus, the airway should be cleared and examined for patency. Loss of support of subglottic musculature can result from severe mandibular fractures, and the tongue can fall posteriorly and occlude the airway in a patient with a depressed mental status. An oral or nasal airway may serve as an adjuvant to positioning in order to achieve airway patency. Tracheal intubation may be required if the airway remains unstable. Cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy may be necessary if these measures fail to secure the airway but should be attempted only as a last resort because of the technical difficulty and complications associated with such procedures, particularly in young children.

Cervical Spine Protection

Up to 10% of patients with maxillofacial trauma have an associated cervical spine injury. Patients with tenderness of the cervical spine, impaired sensorium, focal neurologic deficits, or major distracting injury should be placed in a hard cervical collar until an injury to the cervical spine can be excluded.

Identification of Specific Bony Injuries and Facial Neurologic Deficits

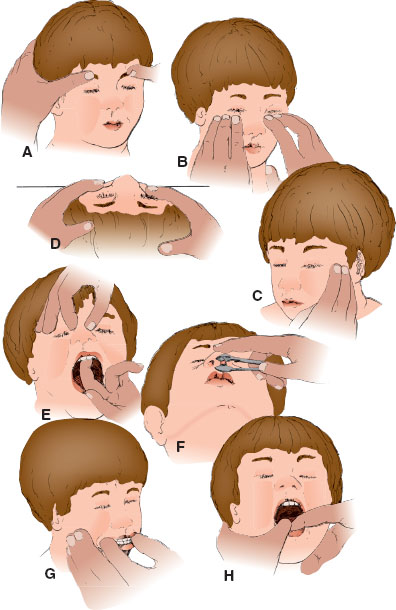

Following airway stabilization and cervical spine protection, examination for specific bony injuries should be performed. After careful observation for deformity and asymmetry, the clinician should palpate the facial bones in a systematic fashion (Fig. 115.1). Tenderness, crepitus, and “step off” are signs of underlying fracture. Particular attention should be paid to the malar eminences, zygomatic arches, and superior and inferior orbital rims.

Assessment for a fracture of the maxilla can be performed by grasping and attempting to move the upper central teeth. Any laxity of the maxilla or crepitus is suggestive of fracture. External and intraoral palpation of the mandibular symphysis, body, angle, and ramus can help diagnose fractures in these areas. Inspection of the mouth and oral cavity should also be performed to assess for injury to the maxilla and mandible. Occlusal disharmony is an indication of mandibular and/or maxillary displacement. Older children will be able to report if their bite “feels normal.” Opposing teeth that do not come together, but that exhibit wear facets (smoothing of mammillations along the incisal surfaces of the teeth) suggest a traumatic malocclusion. An inability to hold a tongue blade between occluded teeth on each side of the mouth is suggestive of a mandibular fracture.

Examination of the eyes should include the assessment of pupillary reactivity and size, examination of extraocular movements, visual acuity, and a thorough inspection for surrounding orbital injuries. Orbital dystopia and/or enophthalmos are suggestive of a fracture of the orbit. Examination of the nose should include documentation of focal tenderness, swelling and asymmetry, bleeding, or other nasal discharge, as well as the presence or absence of a septal hematoma.

FIGURE 115.1 Sequential steps in examination for facial fractures. A: The supraorbital ridges are palpated while keeping the patient’s head steady. B: The infraorbital ridges are palpated using the index, middle, and ring fingers to assess for areas of point tenderness. C: The zygomatic arch is palpated on each side to determine continuity and the possible presence of displaced fractures. D: The infraorbital rims, zygomatic bodies, and maxilla are palpated and examined from the top of the head to determine depressions and fracture displacement. E: The nasal bone and maxilla are examined for stability and possible fracture displacement. F: The nose is examined intranasally to determine the placement of the nasal septum and the possible displacement of nasal bones or disruption of nasal mucosa. G: The occlusion is observed to determine any disturbances of normal teeth relations. H: The mandible is palpated and then retracted to determine sites of discomfort and possible mandibular fractures.

Neurologic examination of the face should include evaluation of both sensory and motor functions. All three branches of the trigeminal nerve should be evaluated for sensation. Anesthesia of the cheek suggests injury to the infraorbital nerve, whereas anesthesia of the lower teeth and lower lip suggests inferior alveolar nerve involvement. The facial nerve should be evaluated by asking the patient to wrinkle the forehead, close and open the eyes fully, smile, show his or her teeth, and close the mouth tightly.

Determination of Appropriate Imaging Modality

The use of radiography in the evaluation and management of children with facial trauma should be considered if there is a concern of fracture based on history and physical examination. The complexity of bony and soft tissue facial structures can make the interpretation of plain radiographs difficult. In addition, plain radiographs are often inadequate to determine whether a patient requires operative intervention.

Computed tomography (CT) has mainly replaced plain radiographs in the definitive assessment of bony facial injuries because it has a greater ability to detect fractures and associated displacement as well as visualize soft tissue structures. Axial views demonstrate fractures of the anterior and posterior walls of the frontal sinus, medial and lateral orbital walls, posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, zygomatic arches, and mandible. Coronal views demonstrate fractures of the ethmoid, sphenoid, and paranasal sinuses; orbital floors and infraorbital rims; the nasoethmoid region; and mandibular condyles and symphyses. Coronal imaging requires hyperextension of the neck and thus requires prior exclusion of a cervical spine injury. Three-dimensional CT imaging can help guide operative repair.

Despite their limitations, there are specific plain radiograph views that may be of utility for the evaluation of facial fractures in children. The Waters view (occipitomental) is used to visualize the midface region: the orbital rims and floor of the orbit, nasal bones, zygoma, and maxilla. This view may be particularly useful in patients suspected of having a blowout fracture of the orbit, as well as for detecting fluid in the maxillary sinus. The Caldwell view supplements the Waters view for the evaluation of the upper two-thirds of the face, including visualization of the superior orbital rim, frontal sinuses, and nasoethmoid complex; however, the orbital floor is often obscured. The lateral view is useful for the detection of fractures to the anterior wall of the frontal sinus, the anterior and posterior walls of the maxillary sinus, and the nasal bones. The submentovertex view provides visualization of the zygomatic body and arch. Posterior–anterior, right and left lateral oblique, and Towne views are used to detect fractures of the mandible; however, fractures of the symphysis may be difficult to discern. Panorex views provide visualization of the entire mandible and lower teeth.

Obtain Subspecialty Consultation When Indicated

The clinician must evaluate whether subspecialist input is warranted for the management of facial trauma in children. Plastic surgeons, ophthalmologists, otorhinolaryngologists, and oral and maxillofacial surgeons have expertise in the management of patients with facial trauma. Once it is determined that subspecialist input is warranted, the decision of which subspecialist to involve will depend largely on availability and expertise of such individuals within the institution.

FACIAL FRACTURES

Mandible Fracture

Goals of Treatment

The primary goals in treatment of mandible fractures include (1) airway stabilization, (2) pain control, and (3) evaluation for the need for subspecialty consultation and possible surgical intervention.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Clinical evaluation of any chin laceration should include palpation of the mandible, particularly the mandibular condyles, to evaluate for mandible fracture.

• The majority of mandibular fractures can be managed conservatively with closed reduction and/or maxilla–mandibular fixation.

• Preauricular swelling and inability to fully close the mouth are key features of temporomandibular joint dislocation.

Clinical Considerations

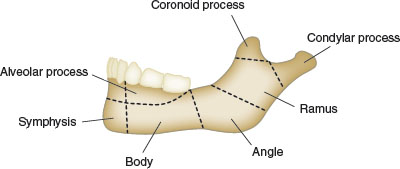

Fractures of the mandible can occur in one or more of the following regions: the symphysis, body, angle, ramus, and condyle (Fig. 115.2). The mechanism of injury often determines the site of potential fracture in patients with trauma to the mandible. Motor vehicle collisions and falls tend to cause fractures of the condyles and symphysis because the force is directed against the chin, whereas assaults tend to result in injuries to the body or angle of the mandible at the point of impact. Patients with parasymphyseal fractures resulting from falls often have an associated fracture in the contralateral subcondylar region. Pain and difficulty opening the mouth are typically present with mandibular fractures. Numbness of the lip and chin may also suggest a mandibular fracture because the inferior alveolar nerve courses through the center of the mandible, from the middle of the ramus, to its exit at the mental foramen. Mandibular fractures may result in airway obstruction due to hemorrhage either from the floor of the mouth or from a disruption in the bony support structure for the tongue.

Powerful muscles of mastication apply distracting forces to the fractured mandibular segments, often resulting in bony displacement and occlusal disharmony. The growth center for the mandible is located in the area of the condyle, and damage to this area from a fracture can cause significant growth disturbances, especially if sustained before the age of 3 years. Therefore, the clinical evaluation of any chin laceration should include palpation of the mandible, particularly the condyles. Malalignment of the lower central incisors (i.e., step off in dentition) suggests a mandibular fracture at the symphysis. Unilateral condyle fractures will most often result in the deviation of the jaw toward the side of the fracture upon mouth opening.

Temporomandibular joint dislocation may not only result from a direct blow to the chin but also may occur while yawning or opening the mouth widely. With dislocation, the condyle of the mandible is displaced anteriorly and is prevented from sliding back into place by spasm of the jaw muscles. Preauricular swelling and inability to close the mouth fully are the key features on physical examination.

FIGURE 115.2 Anatomy of the mandible. Common sites of fracture include the condyle and subcondylar region, as well as the angle, body, and symphysis of the mandible.

Current Evidence

Mandibular fractures are treated more conservatively in children compared to adults due to the risk of injury to the permanent tooth buds and mandibular growth retardation. Most mandibular fractures can be treated with closed reduction and maxillomandibular fixation. A soft or liquid diet is recommended. Displaced fractures commonly require open reduction, internal fixation, or the use of splints. Antibiotics are generally recommended as these fractures are often in communication with the oral cavity, although there is limited data to support this recommendation.

Reduction of temporomandibular joint dislocations may be facilitated with the use of a benzodiazepine to decrease muscle spasm; procedural sedation may also be required. Downward traction is applied to the posterior aspect of the mandible. The chin is then pushed posteriorly to allow the condyle to return to its fossa.

Orbital Fracture

Goals of Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree