Chapter 41 Facial, Ocular, ENT, and Dental Trauma

Trauma to the maxillofacial region of the body affects as many as 80% of patients with multiple traumatic injuries.1 Common sources of maxillofacial trauma include the following:

Traditionally, the majority of facial trauma cases were related to motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), but with the introduction and enforcement of prevention strategies such as airbags and seat belts, the incidence of maxillofacial trauma secondary to MVCs has declined significantly. As a result, IPV has overtaken MVCs as the leading cause of trauma to the face.2

The face is a frequent target in IPV, also known as domestic abuse. Between 34% and 73% of woman who present with trauma to the face will have sustained the injury because of IPV, but many of these victims will attempt to mask the source of their injury by providing false stories such as “I walked into a door” or “I hit my head on the corner of a coffee table.”3 The emergency nurse should always evaluate the degree of injury with the history provided, looking for inconsistencies, and use these opportunities to open a dialogue with these patients about breaking the cycle of violence. Refer to Chapter 50, Intimate Partner Violence, for more information.

Trauma to the facial region has far-reaching effects on an individual.

• The face is the beginning of both the respiratory and the gastrointestinal tract, and facial trauma often affects both of these systems.

• The face sits directly in front of the cranial vault and is held up by the neck; brain injury and spinal cord trauma are commonly associated with facial injuries.

• The face houses three of the five senses (taste, smell, and sight) and is closely associated with hearing and touch; as well, it plays an integral role in speech. Therefore interaction with the world can be negatively affected by maxillofacial trauma.

• The face is an important part of a person’s identity, leaving a patient with facial trauma to deal with significant psychological impacts long after the initial injury.

Primary Assessment

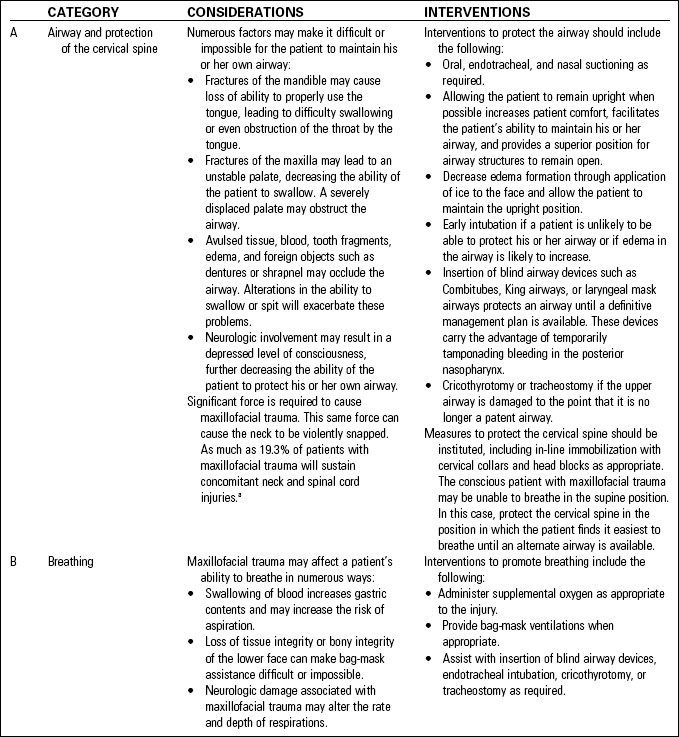

Assessing the patient with maxillofacial and ocular trauma is no different than assessing a patient with trauma to other body systems. The ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation) of trauma assessment are a priority. Table 41-1 describes the primary assessment of the patient with facial trauma.

Secondary Assessment

• Inspecting the face for asymmetry, performing a side-to-side comparison of the eyebrows, infraorbital rims, zygomatic arches, anterior sinus walls, jaw angles, bridge of nose, and lower mandibular borders. At times, a “bird’s-eye” view of the patient, performed by standing at the head of the patient and looking across the patient’s forehead to the face, will reveal deformities that are not evident when looking directly at a patient.

• Palpating the face, noting areas of palpable tenderness, crepitus, or bony deformities while simultaneously assessing for areas of numbness on the face.

• Assessing for mandibular injury by asking the patient to open and close the mouth. Patients with mandibular fractures or temporomandibular joint injuries may have difficulty doing so.

• Asking the patient to follow fingers as they move in various directions. The eyes should move simultaneously through all visual fields. Inability to move the eyes in all directions may indicate orbital wall fractures; injuries to cranial nerves III, IV, or VI; or ocular injuries.

• Assessing the cranial nerves associated with the face (Table 41-2).

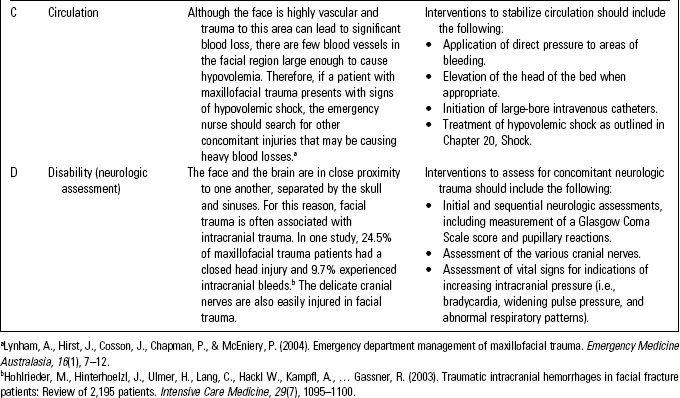

TABLE 41-2 ASSESSMENT OF THE CRANIAL NERVES

| CRANIAL NERVE | ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE |

|---|---|

| I | Have the patient identify a smell. |

| II | Perform a visual acuity test. |

| III, IV, and VI | Have the patient move their eyes through the various visual fields and test for pupil reactivity. |

| V | Touch a wisp of cotton to various areas of the patient’s face looking for areas of altered sensation. |

| VII | Check symmetry and mobility of the face by having the patient frown, close the eyes, lift the eyebrows, and puff the cheeks. |

| VIII | Test hearing acuity. |

| IX and X | Listen to the sound of the patient’s voice; it should be smooth. Assess for the presence of both the gag and the swallowing reflex. |

| XI | Have the patient rotate the head and shrug the shoulders against resistance. |

| XII | Ask the patient to stick out his or her tongue or say the sounds of the letters L, T, and D. |

Facial Soft Tissue Trauma

Numerous considerations are unique when dealing with soft tissue trauma to the face.

• Because the face is highly vascular and tends to bleed longer, wound closure may be delayed as long as 20 hours from the time of injury (as opposed to 4 to 6 hours on other parts of the body).

• “Road rash” to the face may result in permanent epidermal staining (tattooing) from imbedded grease or asphalt. Gunpowder can also permanently stain the face. Application of topical anesthetic followed by scrubbing with a hard brush over areas of road rash will minimize these effects.

• Lacerations involving the eyelids and eyebrows should receive a high triage priority to facilitate rapid closure before edema makes wound edge approximation difficult. Eyebrows should never be shaved, as they may not grow back. They also serve as an anatomic guide for proper wound closure.

• Because of the long-term psychological consequences of scarring, plastic surgery consultation may be considered for facial wounds. This is especially true of lacerations through the lip border to assure that the vermilion border is aligned.

• Wounds inside the mouth, including those on the tongue, carry a higher risk of infection. Carefully inspect these wounds for debris and tooth fragments. Antibiotics are frequently prescribed.

• Lacerations of the cheek may be associated with injuries to the parotid gland and parotid ducts. Clear drainage from the wound is one indication that these glands or ducts are injured.

• Because vasoconstriction on small body parts can lead to significant tissue ischemia, lacerations of the ear and nose are generally closed using anesthetic without epinephrine.

Therapeutic Interventions

• Apply direct pressure and ice to actively bleeding facial wounds.

• Anesthetic with epinephrine is often used on facial wounds to decrease bleeding. Anesthetic without epinephrine is more likely to be used on wounds of the nose or ears.

• Elevate the head of the bed if cervical spinal injuries are not suspected.

• Assist with wound cleansing. Scrub abrasions to remove imbedded material, irrigate other wounds with copious amounts of wound irrigant. Bite wounds tend to be significantly contaminated and will require scrupulous cleansing.

• Consider the need for tetanus prophylaxis.

• Consider the possibility of abuse or crime as the underlying cause and report as per hospital policy and local reporting requirements.

Patient and Family Teaching

• Because of the vascularity of the face and its thin skin, it heals faster. Therefore instruct the patient to return for suture removal within 3 to 5 days.4 Sutures in the ear are usually left in for 10 to 14 days.5

• If wound glue is used for wound closure, instruct the patient to keep the area clean and dry and avoid application of petroleum-based products (such as antibiotic ointment) that can break down the adhesive. The glue will slough off in 5 to 10 days.

• Instruct the patient to apply sunblock with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 15 to the wound for at least 6 months to prevent discoloration of the wound.4

• Teach the patient to return if there are signs of infection, including redness, swelling, warmth, or discharge from the area.

Auricular Trauma

Therapeutic Interventions

• Cleanse the wound, removing any obvious dirt or debris.

• Grossly contaminated wounds may require systemic antibiotics.

• Lacerations are debrided prior to repair. A plastic surgeon may be asked to do the repair to ensure acceptable cosmetic results. The skin is carefully pulled over any exposed cartilage and care must be taken that sutures are not passed through cartilage because this can lead to further damage.

• Complete amputation of the ear will require surgical intervention for reattachment.

• Hematomas of the pinna are aspirated using a large-bore needle or a small stab incision. A drain may be placed to facilitate continued drainage of the area. After the area has been drained, a pressure dressing is applied to the area to prevent blood reaccumulation.

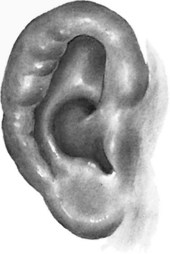

• Figure 41-1 shows “cauliflower ear,” a deformity of the external ear that can result from auricular trauma.

Fig. 41-1 Cauliflower ear.

(From Gisness, C. M. [2010]. Maxillofacial trauma. In Emergency Nurses Association, Sheehy’s emergency nursing: Principles and practice [6th ed., pp. 355–363]. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.)

Ruptured Tympanic Membrane

Signs and Symptoms

• Sudden sharp ear pain at the time of the rupture

• Blood or purulent drainage from the ear canal

• Hearing impairment (proportional to the size of the perforation)

Therapeutic Interventions

• Do not irrigate the ear to prevent fluid from damaging the structures normally protected by the eardrum.

• Antibiotics are indicated if there is a history of ear contamination.

• Ninety percent of perforations will heal spontaneously but large perforations may require surgical repair.

• Instruct the patient and family:

Facial Fractures

Nasal Fractures

The most frequently fractured bones of the face are the nasal bones, accounting for 39% to 45% of all facial fractures.6 While fractures of the nasal bones are typically less serious than other facial fractures, serious complications such as septal hematomas, epistaxis with excessive blood loss, and basilar skull fractures need to be ruled out.

Signs and Symptoms

Therapeutic Interventions

• Control bleeding with direct pressure or pinching the nares. If this is unsuccessful, application of topical vasoconstrictors or packing may be considered.

• Splint the nose as indicated.

• Closed or open reduction may be necessary if fracture is displaced, but surgery is usually delayed until after the swelling has abated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree