INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Lacerations of the face and scalp are proximate in location but have important differences regarding repair. Facial wounds are the most cosmetically apparent of all wounds and therefore warrant careful evaluation and meticulous repair technique for the best possible outcome. Scalp wounds are less visible and are typically closed with less attention to detail. Most facial and scalp lacerations can be closed by the emergency physician, but consult with specialists if the technical aspects of closure are complex.

Three common principles guide repair of facial and scalp lacerations.1 First, cleanse, irrigate, and remove foreign material to minimize infection. Second, limit debridement of skin edges because the excellent blood supply enables tissues to recover that initially appear nonviable. And third, if local anesthetic infiltration distorts anatomy and hinders wound edge alignment, use regional nerve blocks (see chapter 36, “Local and Regional Anesthesia”).2

Use nonabsorbable monofilament suture for facial skin. Rapidly absorbable suture and tissue adhesives are alternatives in selected locations and for children.3,4 Use absorbable suture for mucosa and facial layers. To minimize scarring, place percutaneous sutures on the face 1 to 2 mm from the wound edges, 3 to 4 mm apart, with everted edges. Place mucosal sutures 2 to 3 mm from the wound edges, 5 to 7 mm apart, and superficial so as to only include the mucosa and not the underlying muscle or fascia. Use of magnification with surgical loupes may facilitate more accurate suture placement in facial wounds.

Ask about the possibility of domestic violence in patients with facial injuries, and notify appropriate authorities if violence is suspected (Table 42-1).5,6,7

Most victims of domestic violence have maxillofacial injuries. Women are more commonly affected than men. Fist is most common weapon. Left side of face is most common site of injury (from right-hand-dominant assailants). Nasal bone is commonly fractured. |

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

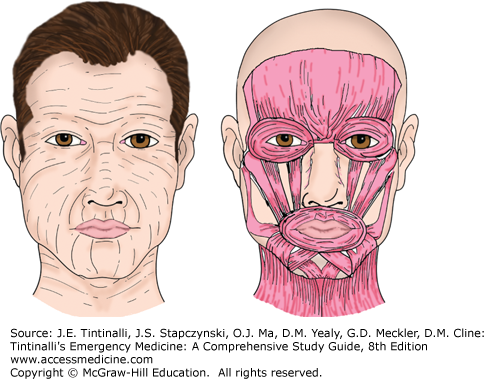

Facial and scalp wounds are most often caused by a combination of sharp and blunt mechanisms. Lacerations caused by sharp objects likely have discrete edges but may extend deeply and involve underlying structures, such as the muscles of facial expression, nerves, and arteries. Wounds caused by blunt forces burst the skin open, damage cells, and produce tissue edema, all of which slow the wound-healing process. As a result, it takes an average of 10 times fewer bacteria to cause an infection in a blunt wound compared with a sharp wound. Blunt forces are also more likely to cause diffuse underlying damage, such as fractures of the facial bones or skull.

In most patients with isolated facial trauma resulting in lacerations, the incidence of facial fractures is low, especially in children.8 However, in multiply injured patients, suspect underlying fracture in facial lacerations involving the infraorbital area, zygoma, nose, lips, and intraoral mucosa, so perform careful physical examination and obtain facial CT scans.9,10

Facial and scalp lacerations have a low incidence of postrepair infection, so primary closure can usually be done in wounds that are not obviously infected, regardless of the duration of time since the injury11,12,13 or even if injury was from a bite.14,15 The presence of foreign bodies, such as soil, glass, or wood fragments, complicates wound healing.13

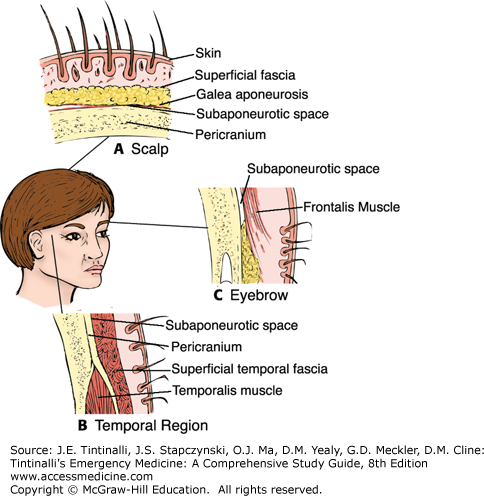

SCALP AND FOREHEAD

Both the scalp and forehead overlie bone with little cushioning fat and have thick skin (Figure 42-1). The one difference is that the scalp has abundant hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Three branches of the external carotid artery (occipital, superficial temporal, and posterior auricular arteries) and two branches from the internal carotid artery (supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries) provide a rich blood supply to the scalp and forehead. The fibrous dermal tissue limits vessel retraction after injury, so significant hemorrhage can result from an arterial laceration. The potential space between the pericranium (periosteum covering the external surface of the skull bones) and the galea aponeurosis that allows for easy movement of the scalp over the cranium also enables hematoma and infection to collect in this subaponeurotic space and spread to involve the entire forehead and scalp. This high degree of mobility sometimes leads to a scalping injury, in which a large segment of the scalp is torn off in one piece.

For some patients with scalp and forehead lacerations, the wound may be only a minor part of the overall injury. Perform a focused assessment looking for intracranial injury before definitive wound care. Control scalp hemorrhage by applying direct pressure or clamping the involved vessel(s) at the wound edges (e.g., using Raney clips; see chapter 40) until the assessment is completed.16

Inspect scalp lacerations, and gently palpate with a gloved finger to determine depth and to identify galeal laceration or depressed skull fracture. Evaluate palpable depressions with a CT scan. Orientation of forehead lacerations has important cosmetic implications. In general, forehead wounds that fall parallel to the lines of skin tension have better cosmetic results than wounds that are perpendicular. The horizontal lines seen on the forehead when the brow is raised are perpendicular to the frontalis muscle underneath (Figure 42-2).

Children may need sedation for wound repair (see chapter 113, “Pain Management and Procedural Sedation in Infants and Children”). Anesthesia can be provided by topical, local, or regional infiltration. Topical agents alone, such as lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine, provide adequate anesthesia in about half of patients and reduce the pain of local anesthetic injection.17,18,19,20 Local anesthetics containing epinephrine are often used in highly vascular wounds to help control hemorrhage from small vessels.

Irrigate (see chapter 40, “Wound Preparation”) to reduce contamination and lessen the risk of wound infection. Appropriate pressure for irrigation can be accomplished with a 30-mL syringe and 18-gauge IV catheter or commercially available irrigation device. However, in resource-poor situations, because the face and scalp are highly vascular, clean-appearing wounds have been repaired using adhesive strips, without prior cleansing and irrigation.21

Do not shave hair before wound closure, because shaving increases the risk of infection.22 To visualize the injured area, brush the hair aside or matt it down with an ointment, such as bacitracin zinc or petrolatum.23 If visualization is still difficult, trim the adjacent scalp hair with scissors.

Suture accessible lacerations of the galea24 to prevent formation of a subgaleal hematoma (Table 42-2).25

| Area | Suture | Size | Anesthetic | Removal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalp | ||||

| Galea | Absorbable | 4-0 | Local | Not removed |

| Skin | Staples | Standard | Local | 14 d |

| Nonabsorbable monofilament | 4-0 | Local | 14 d | |

| Rapidly absorbing | 4-0 | Local | Not removed | |

| Forehead | ||||

| Frontalis muscle | Absorbable | 4-0 | Local or supraorbital nerve block | Not removed |

| Skin | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 5-0 or 6-0 | Local or supraorbital nerve block | 5 d |

| Tissue adhesive | May need deep layer | — | Not removed | |

| Cheek and face | ||||

| Muscle fascia | Absorbable | 4-0 | Local or infraorbital nerve block | Not removed |

| Skin | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 6-0 | Local or infraorbital nerve block | 5 d |

| Rapidly absorbing | 6-0 | Local or infraorbital nerve block | Not removed | |

| Tissue adhesive | May need facial layer closure | — | Not removed | |

| Eyelids | ||||

| Skin | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 6-0 or 7-0 | Supra- or infraorbital nerve block | 3 d |

| Nose | ||||

| Mucosa | Rapidly absorbing | 4-0 | Intranasal | Not removed |

| Cartilage | Nonabsorbable (if necessary) | 5-0 | Intranasal | Not removed |

| Skin | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 6-0 | Local or intranasal | 3–5 d |

| Ears | ||||

| Skin | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 6-0 | Auricular block | 5 d |

| Cartilage | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 5-0 | Auricular block | Not removed |

| Lips | ||||

| Mucosa | Rapidly absorbing | 5-0 | Local, infraorbital, mandibular, or mental nerve block | Not removed |

| Muscle fascia | Absorbable | 4-0 or 5-0 | Local, infraorbital, submandibular, or mental nerve block | Not removed |

| Skin | Nonabsorbable monofilament | 6-0 | Local, infraorbital, or mental nerve block | 3–5 d |

Close scalp skin with surgical staples or simple interrupted percutaneous sutures using nonabsorbable monofilament or rapidly absorbable material.26,27,28,29 Leave suture tails long, and use sutures of a color different than the hair for easy suture removal.

Hair braiding is a technique combining hair apposition and tissue adhesive.30,31,32 In this technique, bring together four to five strands of hair from opposite sides of the wound, twist the strands once, and secure them with a drop of tissue adhesive. This technique requires the wound edges to approximate with little tension, so subcutaneous sutures are sometimes necessary before hair apposition is used to close the skin.

Consider a pressure dressing over a deep scalp laceration for the first 24 hours after repair, to prevent wound hematoma formation.

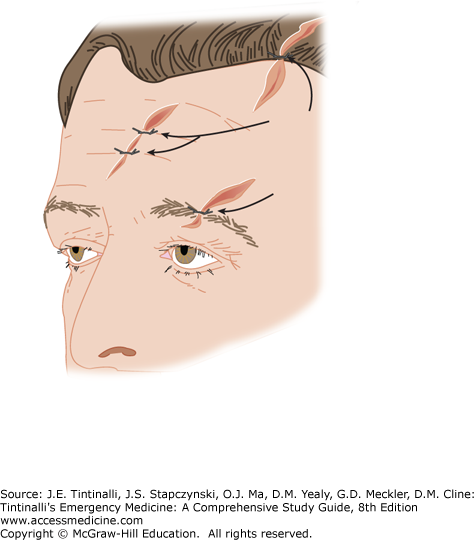

Forehead lacerations are categorized as either superficial, meaning the frontalis muscle is not injured, or deep, meaning the frontalis muscle is involved. For superficial lacerations, close the skin with 6-0 nonabsorbable interrupted suture, rapidly absorbable suture, or tissue adhesive.24,33,34 For deep lacerations, close the muscle layer to avoid noticeable defects, especially when the facial muscles of expression are involved. Close the muscle layer with buried 5-0 absorbable suture. Close the epidermal layer with 6-0 nonabsorbable sutures in a simple, interrupted fashion; with skin closure strips; or with tissue adhesive (Table 42-3).35 Strips or adhesives are especially attractive if the patient is at risk for keloids or hypertrophic scars. Use key stitches to align skin tension lines and the hairline (Figure 42-3).

Do not clip or shave eyebrows because their delicate contour and form are valuable landmarks for wound edge reapproximation. Debridement of loose or nonviable skin in the eyebrow region should be minimal and, if necessary, done so that the remaining hairs preserve as much as possible of the original length, width, and curve of the eyebrow. Use care to align the hair margins. Use sutures that are a different color from the hair and leave long tails to facilitate removal.

EYELIDS

The eyelid is composed of five layers: skin, subcutaneous tissue, orbicularis oculi muscle, tarsal plate, and conjunctiva. The muscular layer controls lid closure and forms both the medial and lateral canthus. Fibers of the orbicularis oculi wrap around the lacrimal system. Nerve supply to the eyelid arises from the temporal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve. The tarsal plate forms the main body of the lower half of the lid and consists of elastic tissue in a dense matrix of connective tissue. Embedded in the tarsal plate are the meibomian glands, which open onto the white line just in front of the conjunctival edge of the lid margin. In the lid margin, the eyelashes are arranged in three irregular rows with their follicles extending obliquely into the tarsal plate.

The lacrimal system begins at the upper and lower puncta that transition into the canaliculi. The canaliculi travel medially into the lacrimal sac that extends inferiorly to the nasolacrimal duct responsible for tear drainage into the nose (Figure 42-4).

FIGURE 42-4.

Periorbital anatomy.