FACIAL CELLULITIS, ERYSIPELAS, AND IMPETIGO

Cellulitis and erysipelas are discussed in detail in the chapter 147, “Soft Tissue Infections.” Impetigo is discussed in the chapter 136, “Rashes in Infants and Children.” The differential diagnosis of facial infections is provided in Table 243-1.1

| Historical Features | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset/Timing | Risk/Inciting Factors | Physical Findings | |

| Infectious | |||

| Cellulitis | Gradual | Skin breaks, foreign bodies, prostheses, immunosuppression | Diffuse erythema without clear borders, pain |

| Impetigo | Acute | Infants, children | Discrete vesicles or bullae; patches of crusty skin |

| Erysipelas | Gradual | Elderly, infants and children, immune deficiency, diabetes, alcoholism, skin ulceration, impaired lymphatic drainage | Well-defined, raised area of erythema, pain |

| Viral exanthem | Often acute | Preceding or concurrent viral illness, fever | Variable |

| Parotitis | Gradual | Dehydration, diabetes, immunosuppression | Swollen angle of mandible, potentially visible sialolith |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Rapid | Trauma, may be minor or not apparent | Crepitus, skin necrosis, may be subtle |

| Cutaneous anthrax | Gradual | Animal contact | Black eschar with surrounding erythema |

| Herpes zoster | Acute | Elderly, immunosuppression | Exquisitely tender erythematous or vesicular rash following a dermatome |

| Malignant otitis externa | Gradual | Diabetes, water exposure | Ear pain with drainage, facial swelling, tragal tenderness |

| Trauma | |||

| Soft tissue contusion | Acute | Associated trauma | Tender swelling |

| Burn | Acute | Occupational, recreational exposure | May be difficult to distinguish from cellulitis |

| Inflammatory | |||

| Insect envenomation | Acute | Environment supporting insect life | Diffuse, red, puffy |

| Apical abscess with secondary buccal swelling | Gradual | Usually associated dental pain/caries | Similar to cellulitis; may have intraoral/gingival findings |

| Contact dermatitis | Gradual or acute | Often identifiable exposure | Variable; maculopapular, itchy rash |

| Immunologic | |||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Gradual | Female-to-male ratio, 9:1 | Erythema in classic “malar” distribution |

| Angioneurotic edema | Acute | Exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, allergen | Lip, oral mucosal swelling, sometimes facial |

| Vancomycin flushing reaction | Acute | Recent exposure to vancomycin | Facial erythema, warmth |

Cellulitis is a superficial soft tissue infection that lacks anatomic constraints.2,3,4 Facial cellulitis is caused most commonly by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic) and Staphylococcus aureus,4 with an increasing predominance of methicillin-resistant S. aureus.5 Less commonly, cellulitis may represent extension from deep space infections (see “Masticator Space Infection” section below). In children, buccal cellulitis from Haemophilus influenzae is now very uncommon if children have received the H. influenzae type b vaccine.6

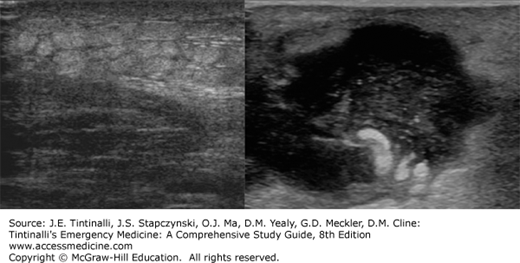

Bedside US can exclude or identify facial abscess (Figure 243-1). CT can identify deep-seated, extensive infections that involve the soft tissues of the neck or pharynx.

Treatment is provided in Table 243-2. Duration of therapy is not well studied, but recommendations range from 7 to 14 days.3,5,7,8 Treatment failures range from 15% to 20% for β-lactams (cephalexin, dicloxacillin, and amoxicillin-clavulanate) as well as for the anti–methicillin-resistant S. aureus therapies9 due to the failure to cover methicillin-resistant S. aureus and streptococcal species, respectively. Cephalexin appears to be the most cost-effective therapy based on a probability of 37% for infection with S. aureus and a 27% methicillin-resistant S. aureus prevalence.10 In selected cases, traditional β-lactam therapy may be added to anti-methicillin-resistant S. aureus therapy, but this strategy increases cost and potential for adverse effects of the medication.

| Cellulitis | Oral therapy: dicloxacillin, cephalexin, clindamycin; vancomycin and cephalosporins are alternatives Suspected MRSA: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, doxycycline, minocycline, linezolid Parenteral therapy: nafcillin, vancomycin, clindamycin Total duration 7–10 d |

| Erysipelas | Oral therapy: penicillin (only if MRSA is unlikely) Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus suspected: amoxicillin-clavulanate, cephalexin, dicloxacillin Bullous erysipelas (or MRSA suspected): trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, doxycycline, or minocycline Parenteral therapy: vancomycin, nafcillin, clindamycin Total duration 7–10 d |

| Impetigo | Topical: mupirocin or retapamulin ointment alone or with oral therapy Oral therapy: dicloxacillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, cephalexin Alternative: azithromycin MRSA suspected: clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole Total duration 7 d3 |

| Suppurative parotitis | Parental therapy: nafcillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate or ampicillin-sulbactam; if penicillin allergic, clindamycin or the combination of cephalexin with metronidazole, or vancomycin with metronidazole Hospital acquired or nursing home patients: consider vancomycin Total duration: 10–14 d |

| Masticator space infection | Parenteral therapy: IV clindamycin is recommended; alternatives include ampicillin-sulbactam, cefoxitin, or the combination of penicillin with metronidazole Oral therapy: clindamycin or amoxicillin-clavulanate Total duration: 10–14 d |

Erysipelas is most common in the lower extremities (66% to 76%)11,12,13 but is classically described as a disease of the face (see Figure 152-3). The nasopharynx is typically the source of bacteria.14 In the majority of cases, erysipelas is caused by S. pyogenes.3,4 Bullous erysipelas is a more severe form of the disease, and half of the infections reported in a 2004 case series were due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus.15 Penicillin is the antibiotic treatment of choice3,13 but is chosen as empiric therapy in a minority of cases.11,12,16,17 If the suspicion exists of a staphylococcal infection (i.e., bullae, trauma, or the presence of a foreign body), alternatives include dicloxacillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or a cephalosporin3 (Table 243-2). One randomized, prospective trial compared the use of a macrolide, roxithromycin, with penicillin and found no difference in efficacy.18

Impetigo is a discrete, superficial bacterial epidermal infection, characterized by amber crusts (nonbullous) or by fluid-filled vesicles (bullous) (see Figures 141-14 and 141-15). It is most common in children. S. aureus alone or in combination with S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic) is the most common cause of nonbullous impetigo. Bullous impetigo is always caused by S. aureus.3,19,20 Treatment should cover streptococcal and staphylococcal species. Topical therapy is sufficient for uncomplicated patients with only a few nonbullous lesions.21 Mupirocin, retapamulin, or fusidic acid ointment is recommended; however, some resistance is developing.3,20,22,23 Consider oral antibiotics for extensive lesions or lesions that do not respond to topical therapy alone. Erythromycin and cloxacillin are superior to penicillin, but there is no clear preference between macrolides, β-lactamase–resistant penicillins, and cephalosporins.3,19 Preferred choices are penicillinase-resistant penicillins (cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) or first-generation cephalosporins (cephalexin).3 For methicillin-resistant S. aureus, treat with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin3 (Table 243-3).

| Antibiotic | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Oral Antibiotics | |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | 875/125 milligrams twice per day |

| Azithromycin | 500 milligrams first day, 250 milligrams 4 more days |

| Cephalexin | 500 milligrams four times per day |

| Clindamycin | 300–450 milligrams three times per day |

| Dicloxacillin | 500 milligrams four times per day |

| Doxycycline | 100 milligrams twice per day |

| Metronidazole | 500 milligrams every 8 h |

| Minocycline | 100 milligrams twice per day |

| Penicillin V | 500 milligrams four times per day |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 1 double-strength tablet twice per day |

| Parenteral Antibiotics | |

| Antibiotic | Dosage |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 1.5–3.0 grams every 6 h |

| Clindamycin | 600 milligrams every 8 h |

| Cefazolin | 1 gram every 8 h |

| Metronidazole | 1 gram loading dose, then 500 milligrams every 8 h |

| Nafcillin | 1–2 grams every 4 h |

| Penicillin G | 2–3 million units every 6 h |

| Vancomycin | 1 gram every 12 h |

SALIVARY GLAND INFECTIONS

There are three groups of salivary glands: the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual. The facial nerve passes through the superficial portion of the parotid gland, and the parotid (Stensen’s) duct opens into the mouth opposite the upper second molar. The submandibular and sublingual glands lie below the plane of the tongue. The submandibular ducts open into the mouth at either side of the frenulum of the tongue. The multiple sublingual ducts open into the sublingual fold or directly into the submandibular duct.24

Signs of salivary gland infections are unilateral or bilateral facial swelling. Recurrent symptoms, dry mouth and eyes, or joint symptoms suggest etiologies such as immunologic or collagen vascular disorders. Other medical conditions, such as nutritional disorders, toxic exposures, diabetes, dehydration, medication usage (i.e., phenothiazines), pregnancy, and obesity, can result in salivary gland enlargement. On physical examination, determine the location of the swelling to identify the gland involved. Multiple gland involvement suggests infection. A palpable tender mass may be a sign of tumor or obstruction by a stone. The differential diagnosis of salivary gland swelling is provided in Table 243-4.24

| Historical Features | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Risks/Inciting Factors | Clinical Features | |

| Infectious | |||

| Viral parotitis (mumps) | Gradual | Nonimmunized | Prodromal illness, unilateral tense swelling, absent warmth/erythema |

| Buccal cellulitis | Gradual | Haemophilus influenzae infection in nonimmunized | Erythematous, tender |

| Suppurative parotitis | Rapid | Dehydration, immunosuppression, chronic illness, recent anesthesia | Painful buccal swelling, fever, pus expression from Stensen’s duct |

| Masseter space abscess | Gradual | Dental infection, post trauma | Trismus, posterior inferior facial swelling |

| Tuberculosis | Gradual | Exposure, immunosuppression | Chronic crusting plaques |

| Immunologic | |||

| Sjögren’s syndrome | Gradual | — | Dry mouth, eyes, sclerosis |

| Systemic lupus | Gradual | Female sex, Asian or African American race | No signs of infection |

| Sarcoidosis | Gradual | Female sex, African American race | No signs of infection |

| Other | |||

| Neoplasm | Gradual | — | No erythema, warmth |

| Sialolithiasis | Gradual | Dehydration, chronic illness | Swelling, tenderness, no signs of infection |

Viral parotitis is an acute infection of the parotid glands, characterized by unilateral or bilateral parotid swelling. It is most often caused by the paramyxovirus and may be caused less commonly by influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackie viruses, echoviruses, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, and even human immunodeficiency virus.25 It is most common in children under the age of 15 years old, but since November 2014, clusters of mumps have been reported in adult members of professional hockey teams. The virus is spread by airborne droplets, incubates in the upper respiratory tract for 2 to 3 weeks, and then spreads systemically. Vaccine protection is not 100%, and outbreaks occur in settings of close contact, such as schools, colleges, sports teams, and camps.26

After a period of incubation, one third of patients experience a prodrome of fever, malaise, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, and anorexia during a 3- to 5-day period of viremia.25 The classic salivary gland swelling then follows. Unilateral swelling is typically followed by bilateral parotid involvement. The gland is tense and painful, but erythema and warmth are notably absent. Stensen’s duct may be inflamed, but no pus can be expressed.25

Diagnosis is clinical and treatment is supportive. Salivary gland swelling typically lasts from 1 to 5 days. The patient is contagious for 9 days after the onset of parotid swelling, and children with mumps should be excluded from school or day care for this interval.

Mumps is usually benign in children but can be severe in adults. Unilateral orchitis affects 20% to 30% of males (with a predisposition of ≥8 years of age), whereas oophoritis affects only 5% of females. Other complications of the mumps virus include mastitis, pancreatitis, aseptic meningitis, sensorineural hearing loss, myocarditis, polyarthritis, hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia.25 Immunocompetent patients with isolated viral parotitis or orchitis can be managed as outpatients. Admit patients with systemic complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree