INTRODUCTION

Pediatric ophthalmologic problems are a common yet challenging issue for all emergency physicians. The history often comes from the parents, particularly in preverbal children, and it may even be difficult for older children to fully articulate their symptoms. The child and the parents need to be calmed and reassured sufficiently to allow for a complete and thorough examination. This chapter includes a review of eye examination techniques and illnesses specific to the care of children. Because the care of pediatric and adult trauma to the eye and its surrounding structures is similar, only those areas of difference are discussed in this chapter. Further discussion of eye emergencies is provided in chapter 241, “Eye Emergencies.”

EYE EXAMINATION IN A CHILD

If a history of chemical exposure is obtained, triage as highest priority, and immediately irrigate the eye with 1 to 2 L of saline.

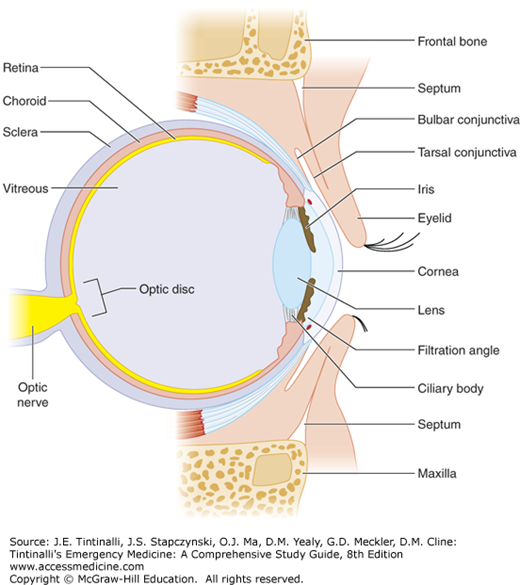

A complete eye exam includes gross examination, assessment of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and ophthalmoscopic exam of the eye. A slit lamp exam of the eye should be performed whenever possible.

Begin by performing a general survey, adopting an outside-in approach, to note any obvious abnormalities such as rash, soft tissue changes, matter on the lashes, ptosis, misalignment of the eyes, injection of the conjunctiva, drainage from the eye, or corneal/lens opacities. Newborns may appear cross-eyed during the first 2 months of life as ocular fixation develops.

Visual acuity (VA) is the vital sign of the eye, and it should be the first objective measurement obtained after the history. Obtaining VA in a child will depend on the child’s age and level of development. A child 6 months to 3 years old should be able to fix and follow a face, toy, or light; a child 3 to 5 years old should have a VA of 20/40 or better with one line acuity difference between eyes; and a child >5 years old should have a VA of 20/25 or better with no acuity difference between eyes.1 Several different eye charts can be used to check distance VA in children, including the Snellen, Allen picture, and tumbling E charts. There is no consensus on the best eye chart for use in young children, but if the child knows letters of the alphabet (typically 4 to 6 years of age), the standard Snellen eye chart should be used. Consider using the tumbling E chart if the child is illiterate or has a cognitive disability. Generally, if the child can identify the letters or objects when standing beside the chart, then it is appropriate to formally test the child’s vision. To use the Snellen chart, check acuity at a distance of 20 ft. Document VA for the lowest line on which four or more characters were correctly identified. One can also chart “20/30 minus 3,” which indicates the patient incorrectly identified three characters in the 20/30 line. When using the Allen picture or tumbling E chart, acuity should be assessed at a distance of 10 ft. from the patient.

If the child cannot stand, use the Rosenbaum near vision card or the Allen reduced picture cards, held at 14 in. (36 cm) from the eyes to check VA. Record which chart was used and the distance at which it was tested.

Check acuity in the nonaffected eye first to establish baseline function. If the child holds his or her hand to cover the eye not being tested, make sure to use the palm and not the fingers, so as not to “peek” or put pressure on the globe. A solid occluding device is preferred. VA should be assessed with the patient wearing corrective lenses. If not available, then use a commercial pinhole occluder or a card with five to six holes created with an 18-gauge needle. If the child is unable to read the top line of an eye chart, then hold up one or more fingers at 3 ft. (1 m) and ask how many fingers are visible. If the child is unable to count fingers, then move your hand from side to side at 1 to 2 ft. (30 to 60 cm) and ask if the child sees motion. Document these responses with the distance your hand is from the patient (i.e., “count fingers at 3 ft.” or “hand motion at 2 ft.”). If the child is unable to see motion, then shine a bright light into the eye and document the presence or absence of light perception.

For VA in children from approximately 3 months to 3 years of age, use a brightly colored object, light source, or moving toy to attract the child’s attention. See if the child is able to follow it with both eyes and then with each eye individually with the opposite eye occluded.

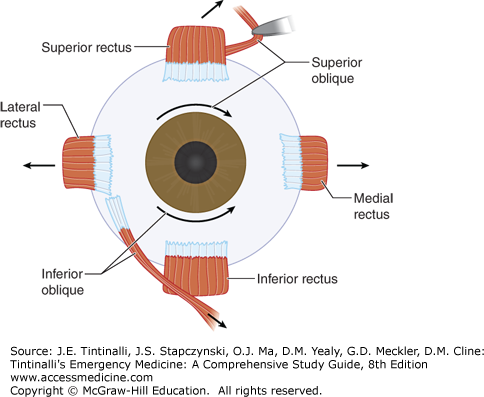

Extraocular movements can be assessed after VA. In cooperative children, have the child follow your finger or an object through the cardinal directions of gaze, often in an “H” pattern, as you would in an adult. In younger children, try using a toy or brightly colored object to direct gaze while the head is held stationary. If this is not possible, the examiner can move the head gently while the child stares at a stationary object to watch the eyes move passively in the orbit.

Relieving pain will make your exam much easier, especially in a child unwilling to open his or her eye. With the patient supine, analgesic drops can be applied to the space between the medial canthus and the nose. The drops will flow into the eye when the child eventually opens his or her eye.2

Older and more cooperative children can be examined sitting independently or on a parent’s lap. Infants, toddlers, developmentally delayed children, and uncooperative children may need to be swaddled in a sheet. Some patients require an eyelid retractor to examine the eye. One can use a standard Desmarres retractor or an eyelid speculum. If neither of these is available, an eyelid retractor can be made from a bent paper clip cleaned with an alcohol swab.

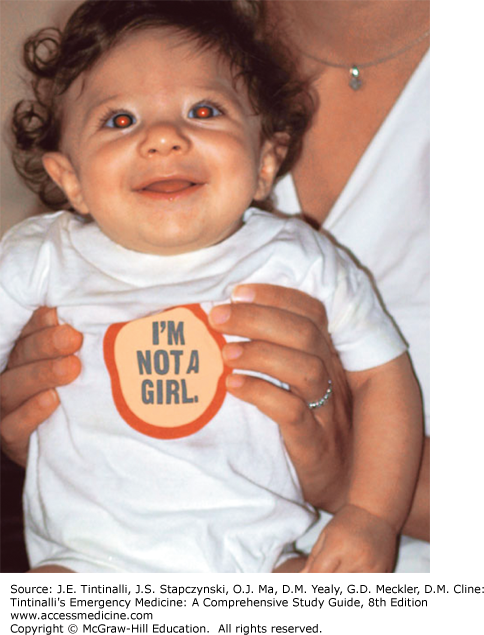

First, document pupil diameter in ambient light. When checking pupil size, have the child focus on a distant object to exclude accommodative miosis and record whether the size was obtained in bright, ambient, or dark illumination. If the difference between pupils is 0.5 mm or greater, then anisocoria exists. A greater size discrepancy in a dark room when compared with a light room indicates physiologic anisocoria, which is of no clinical significance. It is also important to look for leukocoria (white appearance of pupil), which may be indicative of problems with the cornea, lens, or anterior or posterior chamber. Leukocoria is discussed later in the chapter.

Next, check the direct and consensual light reflexes. A bright light source is recommended for children around age 5 years or older. In younger children, a bright light will only cause the child to shut his or her eyes. If the child is old enough to cooperate, have him or her focus on a distant object in the room, such as a brightly colored picture attached to a wall, or have a parent hold up two fingers while standing at the end of the room and direct the child’s attention to the parent. Assess the direct light reflex by shining a light source into the pupil and watching for the pupil to constrict. Then assess the consensual light reflex by shining light into one eye and watching for the pupil of the other eye to constrict. Finally, assess for a relative afferent pupillary defect, a sign of unilateral optic neuropathy. First, shine a light source into one eye, and then swing it to the consensual eye. The consensual pupil should remain constricted in response to the now direct light exposure. If the pupil dilates in response to direct light, a positive relative afferent pupillary defect is present. Repeat the procedure with the other eye and document your observations. Some children will have a small amount of pupillary movement (dilation and contraction) in the consensual eye when the light is swung from the direct to the consensual eye. This is pupillary escape and can be a normal response.

Continue with examination of the red reflex, which should be performed in children of all ages.3 In a dimly lit room, look at the pupils through the direct ophthalmoscope or panoptic scope; position yourself at the patient’s eye level about 1 to 2 ft. away. Document the presence or absence of the red reflex for each eye (Figure 119-5). With older children, perform the same funduscopic examination that you would in an adult.

SPECIFIC PEDIATRIC EYE PROBLEMS

In the following sections, specific eye problems in children are discussed. Eye injuries and eye emergencies also commonly seen in adults are discussed in chapter 241, “Eye Emergencies.”

Strabismus is ocular misalignment. Knowledge of preexisting strabismus helps differentiate between congenital/childhood strabismus and acquired emergent causes of strabismus. Terminology used to describe strabismus is listed in Table 119-1. Normal newborns may have transient misalignment that usually improves by 3 to 4 months of age as the strength of extraocular muscles improves.4

Amblyopia is a loss of VA not correcTable by glasses in an otherwise healthy eye. If children have unilateral visual impairment, their brain will “choose” the image presented by the eye with better vision. If amblyopia is not corrected by about age 10 years old, the brain eventually suppresses visual information presented by the impaired eye, leading to permanent vision loss.

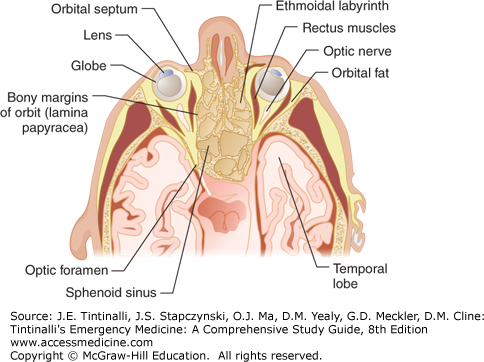

Emergent causes of strabismus include cranial nerve palsy and muscle restriction or entrapment that may be associated with trauma, stroke, tumor, aneurysm, thyroid-associated orbitopathy or other infiltrative process, increased intracranial pressure, or infection. The innervation of the extraocular muscles defines which cranial nerve is involved. Cranial nerve VI innervates the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle, and palsy will lead to esotropia. Cranial nerve IV innervates the ipsilateral superior oblique muscle, and palsy will cause hypertropia. Cranial nerve III innervates all other extraocular muscles, and palsy will lead to exotropia, hypertropia or hypotropia (depending on which branch is affected), and ptosis (Figure 119-4).

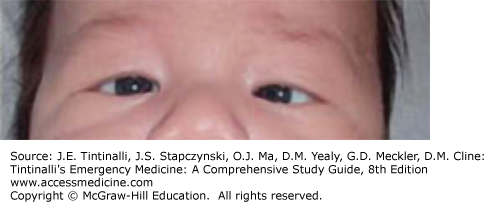

Strabismus is usually suspected after general inspection. Some children have epicanthal folds that lead to pseudostrabismus, or the appearance of ocular misalignment, when the eyes are in fact in proper alignment (Figure 119-6). To identify true strabismus, two simple tests must be performed.

Begin with the Hirschberg test by holding a penlight several feet from the child and observe the reflection of the light on each cornea. In normal ocular alignment, the light reflection will appear on the same position of each eye. Then, a cover test can be performed. Have the child fixate on a distant object and then cover one of the child’s eyes. If the uncovered eye then moves, it can be assumed that it was not properly fixated on the object and strabismus is present. When the eyes are uncovered, they will revert to their original misalignment. Misalignment can further be described as a “tropia,” or constant misalignment, or a “phoria,” or intermittent misalignment, such as when the patient is tired or fusion is broken (Table 119-1). With a “phoria,” the eyes will revert to normal (equal) alignment when both eyes are uncovered.

Historical clues to an emergent cause of strabismus include trauma, diplopia, report of abnormal extraocular movements, sunsetting of the eyes (upgaze deficit), nausea, vomiting, and lethargy. If an emergent cause of strabismus is suspected, obtain imaging directed at the suspected condition.

Congenital strabismus caused by extraocular muscle weakness usually self-resolves in infancy. STable strabismus that persists into childhood should be referred nonemergently to an ophthalmologist. Strabismus caused by amblyopia often resolves with glasses that equalize the vision, although a patch over the “good” eye or surgical correction may be required.

Tears are produced in the lacrimal gland and drain at the medial aspect of the eye through the nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac through the canalicular system to the Hasner valve and finally into the nose. Several common problems seen in pediatrics can arise in the gland and canalicular system.

Dacryostenosis, or nasolacrimal duct obstruction, is a narrowing or obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. It occurs in 6% of all newborns and usually resolves with conservative management.5 Dacryostenosis is a common condition presenting to the ED, and infants may present with epiphoria, eyelash matting, and tears that appear thicker and yellowish in color, which may be mistaken by parents as infection. Fluorescein applied to the eye and left for 5 minutes will accumulate, whereas it normally would be cleared by the lacrimal system. An important clinical feature is the lack of accompanying signs or symptoms, such as fever, irritability, or conjunctivitis. If the conjunctiva are not inflamed, the cause is dacryostenosis with evaporation of the aqueous layer of poorly draining tears, which leaves the yellow mucus layer behind and mimics conjunctivitis.

Treatment of dacryostenosis is supportive and does not require antibiotics. Parents should be taught gentle massage with a downward motion to the nasolacrimal duct three to four times a day. If still present after 12 months of age, ophthalmology referral is indicated for possible dilation of the duct.

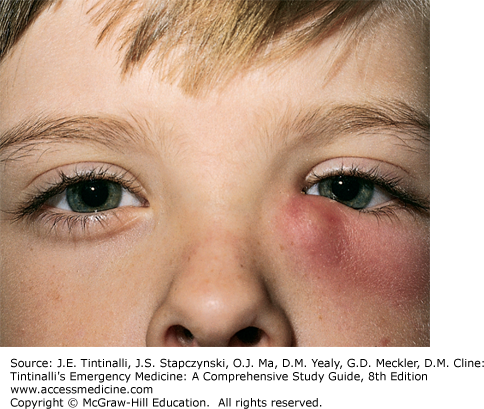

Inflammation and bacterial superinfection of the lacrimal sac will cause dacryocystitis. Common pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, staphylococci, and Haemophilus influenzae.5,6 Patients develop a chronic mucopurulent discharge followed by erythema and swelling inframedially to the eye (Figure 119-7).

In children of all ages, dacryocystitis is usually a secondary bacterial infection following a viral upper respiratory infection. The diagnosis is made when gentle pressure with a finger or cotton swab applied to the nasolacrimal sac causes a reflux of mucopurulent material. The discharge should be cultured to identify the causative agent.

Improperly treated dacryocystitis may lead to periorbital and orbital cellulitis. Children are often quite ill and require hospital admission with parenteral antibiotics until the infection begins to improve.7,8 A cephalosporin, such as cefuroxime (50 milligrams/kg IV every 8 hours) or cefazolin (33 milligrams/kg IV every 8 hours), may be used, or clindamycin (10 milligrams/kg IV every 6 hours) may be used for penicillin-allergic patients. If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected, vancomycin (10 to 13 milligrams/kg IV every 6 to 8 hours) is indicated.7,9

A dacryocele is a small, bluish-hued, palpable mass in the location of the nasolacrimal duct (inferior and medial to the eye) without conjunctival erythema, discharge, or other pathologic findings. It is caused by an obstruction at the valve of Hasner and the common canaliculus.5 Due to possible need for marsupialization, patients should be urgently referred to a pediatric otolaryngologist or ophthalmologist.4

Dacryoadenitis is inflammation of the lacrimal gland and can be acute or chronic. Chronic dacryoadenitis is caused by noninfectious inflammatory disorders such as Sjögren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis, or thyroid disease. Acute dacryoadenitis is usually infectious. In both acute and chronic disease, children will have soft tissue swelling, especially in the region of the lateral upper lid. With infectious causes, systemic symptoms such as malaise and fever may also be present.

Viral dacryoadenitis causes less intense discomfort and erythema than bacterial dacryoadenitis. Causative viral pathogens include Epstein-Barr virus, mumps virus, coxsackievirus, cytomegalovirus, and varicella-zoster virus. Bacterial dacryoadenitis is associated with intense eye discomfort, tenderness, and erythema. The most common causative bacterial pathogen causing dacryoadenitis is S. aureus, but streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Brucella melitensis have also been implicated.7

The first-line treatment of bacterial dacryoadenitis is oral or parenteral antibiotics against S. aureus. For mild infections, an oral first-generation cephalosporin, such as cephalexin (25 milligrams/kg PO every 6 hours), until the infection has resolved is appropriate. If methicillin-resistant S. aureus is suspected, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (20 milligrams/kg PO [or IV] every 12 hours) or linezolid (10 milligrams/kg PO [or IV] every 12 hours) may be used. For more severe infections, parenteral antibiotic therapy is indicated. Nafcillin (37.5 milligrams/kg IV every 6 hours) is appropriate when methicillin-resistant S. aureus is not suspected. Vancomycin (10 to 13 milligrams/kg IV every 6 to 8 hours) is indicated for severe dacryoadenitis caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus.7

Blepharitis is inflammation of the eyelid that may present with eye redness, tearing, photophobia, crusting of the lid margin, swelling, or pruritus. Anterior blepharitis is usually infectious in nature (staphylococci) and affects the base of the eyelashes, whereas posterior blepharitis affects the conjunctival surface of the eyelid and is usually caused by meibomian gland dysfunction.9 Both types of blepharitis are treated with warm compresses and baby shampoo scrubs once to twice daily. Have caregivers apply shampoo to a washcloth and then gently scrub the eyelids. This should be continued until symptoms have resolved completely, which usually requires prolonged treatment. In addition, staphylococcal blepharitis should be treated with erythromycin or bacitracin-polymyxin ointment one to three times a day for 7 days, with the length of treatment depending on severity.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree