CHAPTER 1 Evolution of the Coronary Care Unit

Past, Present, and Future

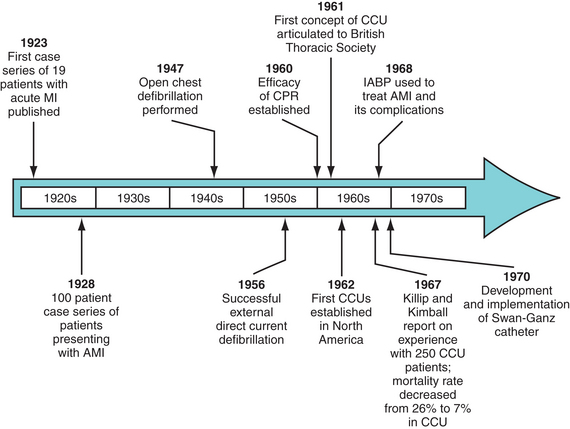

ORIGINATING DURING a time of great technical and investigative discovery, the coronary care unit (CCU) has emerged as one of the most important advances in the care of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Despite the notion that the CCU has revolutionized the management of myocardial infarction (MI), however, widespread proliferation and acceptance of the CCU as “standard of care” has not been met with universal support. Complicating matters further, the CCU has changed considerably over the past several decades, bringing to light unresolved issues of patient triage, medical ethics, physician and nurse training, cost, and resource use. This chapter reviews the evolutionary history of the CCU, from its inception in the early 1960s to its contemporary role in the care of often critically ill patients with cardiovascular disease (Fig. 1-1). Future trends in cardiac care also are addressed, with particular attention given to ways in which the CCU may remain a viable entity within a continuously changing health care system.

Origins of the Coronary Care Unit

Several seminal reviews of acute MI—a highly fatal disease at the time—served to highlight the critical need for improved methods of health care delivery.1,2 Outside of morphine and comfort care measures, there was little available in the clinician’s armamentarium to spare patients with acute MI from death or prolonged convalescence. Treatment of MI at the time has been described as “benign neglect,”3 and even minimal forms of patient exertion were discouraged.

Focus on Resuscitation

The first reasonable therapy to combat complications of myocardial ischemia finally became available after the successful implementation of open-chest4,5 and, later, closed-chest defibrillation.6,7 After reporting on the effective open-chest defibrillation of a patient who developed life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia in the setting of MI, Beck and colleagues5 prophetically reported that “this one experience indicates that resuscitation from a fatal heart attack is not impossible and might be applied to those who die in hospital … and perhaps to those who die outside the hospital.” Following closely on the heels of these discoveries and the demonstrated efficacy of closed-chest massage,8 the concept of the CCU as a vehicle for successful resuscitation began to take shape.

Julian, the senior medical registrar of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, first articulated the idea of the CCU. In his original presentation to the British Thoracic Society in 1961,9 Julian described five cases of cardiac massage used in resuscitation attempts for patients with acute MI. He concluded that “many cases of cardiac arrest associated with acute myocardial ischaemia could be treated successfully if all medical, nursing, and auxiliary staff were trained in closed-chest massage, and if the cardiac rhythm of patients … were monitored by an electrocardiographic linked to an alarm system.” His vision for the CCU was founded on four basic principles, as follows:

At roughly the same time, several clinician investigators in North America developed specialized units devoted exclusively to the treatment of patients with suspected MI. In Philadelphia, Meltzer10 created a two-room research unit with an aperture in the wall through which defibrillator paddles could be passed from one patient to the other. In Toronto, Ontario, Brown and associates11 erected a four-bed unit with an adjacent nursing station for the care of MI patients. Arrhythmia surveillance was provided using a converted electroencephalogram unit with electrocardiogram amplifiers. Although Brown’s initial observations suggested no immediate decline in mortality associated with more attentive coronary care,11 these preliminary findings did little to temper the growing enthusiasm for these specialized units.

Day,12 a contemporary of Meltzer, Brown, and Julian, began building mobile crash carts in the attempt to resuscitate acute MI patients being monitored on the general medical floors. Similar to his colleagues, Day astutely recognized that delays in arrhythmia detection on these general wards significantly limited the success of resuscitation attempts. As a result of his observations, an 11-bed unit was established at Bethany Hospital in New York staffed by “specially-trained nurses who could give the patient with coronary disease expert bedside attention, interpret signs of impending disaster, and quickly institute CPR.”12 Day is largely credited with introducing the term code blue to describe resuscitation efforts for cyanotic patients with cardiac arrest and, perhaps more importantly, the term coronary care unit.

Shift in Paradigms—Prevention of Cardiac Arrest

Until this point, the benefit of specialized care in the CCU was predominantly related to recognition of peri-infarction arrhythmias that were incompatible with life, and the successful termination of such events. It seemed clear to physicians of the time that the development of malignant arrhythmias posed the greatest threat to patients sustaining acute cardiac injury, and perhaps the early recognition and prompt therapy for early prodromata of cardiac arrest might have a significant impact on patient survival. The focus of the CCU moved from one of resuscitation to a more preventive role. Julian13 described this transformation as the “second phase” in the evolution of the CCU.

In the late 1960s, Killip and Kimball14 published their experience with 250 acute MI patients treated in a four-bed CCU at New York Hospital–Cornell Medical Center. Credited largely with the MI classification scheme that now bears their name, in which the presence or absence of heart failure or shock had significant prognostic implications, these two investigators also showed that aggressive medical therapy in the CCU seemed to reduce in-hospital mortality from 26% to 7%. This led Killip and Kimball to proclaim in their landmark report that “the development of the coronary care unit represents one of the most significant advances in the hospital practice of medicine.”14 Not only did it seem that patients with acute MI had improved survival if treated in a CCU, but also all in-hospital cardiac arrest patients seemed more likely to survive if geographically located in the CCU.

“Although frequently sudden, and hence often ‘unexpected,’ the cessation of adequate circulatory function is usually preceded by warning signals.”14 With these words, Killip and Kimball, collectively, with the influential findings of Day, Meltzer, Brown, and others, ushered in the rapid proliferation of CCUs throughout the world, with a categorical focus on the prevention of cardiac arrest.

Truly at the forefront of this new paradigm in coronary care were Lown and colleagues,15 who elaborately detailed the key components of the CCU at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. “From the opening of the unit,” they reported, “the focus has been the prevention of cardiac arrest.” The foundation of their CCU revolved around employment of a “vigilant group of nurses properly indoctrinated in electrocardiographic pattern recognition and qualified to intervene skillfully with a prerehearsed and well-disciplined repertoire of activities in the event of a cardiac arrest.”15 With a CCU mortality of 11.5% and an in-hospital mortality of 16.9%, these investigators concluded that an aggressive protocol emphasizing arrhythmia suppression after MI could virtually eradicate sudden and unexpected fatalities. Although more contemporary data refuting the notion of preventive antiarrhythmic therapy in MI fail to support the early premise of Lown and others,16 their debatable yet compelling results allowed the concept of the CCU to continue to flourish.

Several other developments in the late 1960s through the mid-1980s, including the use of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation,17 the implementation of flow-directed catheters capable of invasive hemodynamic monitoring,18 and the use of systemic thrombolysis for the treatment of coronary thrombosis,19 helped to advance the frontiers of the CCU. Along with these dramatic changes in the care of patients with acute MI came a remarkable transformation in the face and philosophy of the CCU. At the same time, questions and controversies began to emerge regarding the benefits and proper use of these specialized and costly units.

Validating the Benefits of the Coronary Care Unit

Although use of a CCU for the management of patients with acute MI became more commonplace, many still questioned their true impact. These critics pointed to the dubious nature of the early comparisons between CCUs and the general medical wards, most of which were purely observational and experiential reports, and all of which unquestionably lacked the scrupulous scientific and analytic techniques of contemporary clinical research. Adding further fuel to the controversy was a study by Hill and associates20 in the late 1970s comparing outcomes of patients with suspected MI managed at home with outcomes of patients managed in the hospital setting. These investigators found no significant differences in mortality for the two groups, although skeptics cite design flaws, power limitations, and dynamic advances in hospital-based care as major confounders to this study. Nonetheless, results such as these led many, including Cochrane,21 to exclaim, “… the battle for coronary care is just beginning.”

Much of the data in support of the CCU was largely observational. As previously described, Killip and Kimball14 attributed a nearly 20% decline in mortality to the successful implementation of their CCU. Other nonrandomized data from a Veterans Administration population22 and several Scandinavian studies23,24 corroborated the early uncontrolled observations of Killip, Kimball, Day, and others. These trials all showed lower mortality rates and greater resuscitation success in acute MI patients when treated in a CCU setting.

Goldman and Cook25 attempted to ascribe the epidemiologic decline in mortality rates from ischemic heart disease in the United States to the presence of CCUs. From 1968-1976, estimates suggested a decline in mortality of approximately 21%. Using complex statistical analyses and mathematical modeling, the authors surmised that nearly 40% of the decline could be directly attributable to specific medical interventions, with the CCU being one of the premier contributors. They suggested that approximately 85,000 more people would be alive at the end of 8 years because of the presence of CCUs than would have otherwise been alive; in other terms, the CCU may have accounted for approximately 13.5% of the decline in coronary disease–related mortality.25 Epidemiologic estimates from other investigators seemed to corroborate these findings.26

On an even broader scale, Julian13 and Reader27 contemplated that the steady decline in mortality among people 35 to 64 years old in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand since 1967 (the advent of CCUs) may have been a direct effect of the specialized care received in the CCU. More contemporary data, in patients treated during the “thrombolytic era,” have suggested that one highly significant independent predictor of 30-day mortality among acute MI patients was treatment isolated to an internal medicine ward.28 Despite the retrospective nature of this analysis, the findings seemed to underscore the importance of treating acute MI in the setting of an intensive CCU.

Although there are significant limitations to the available data, a plethora of nonrandomized studies seems to support the beneficial role of the CCU in the management of patients with acute cardiac ischemia. A truly randomized, prospective study evaluating the role of the CCU is likely impossible, given the current (albeit arguable) burden of proof in support of these units. Key opinion leaders in the field of cardiovascular medicine have nearly unanimously endowed the CCU as “the single most important advance in the treatment of acute MI.”29,30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree