General Anesthesia

The first description of anesthetic-related deaths was apparently by John Snow in a treatise titled

On Chloroform and Other Anesthetics.

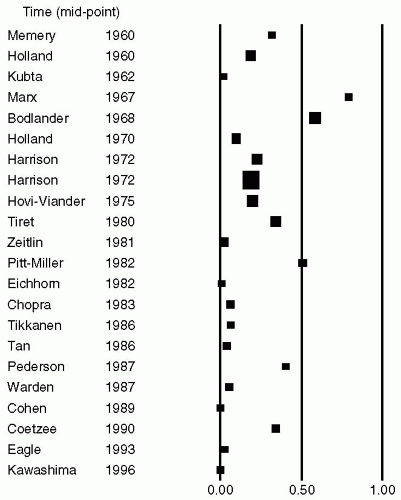

1 Early studies on anesthesia-related postoperative mortality reported an incidence of 1 in 1,500 surgical procedures.

2,

3,

4,

5 These studies concluded that errors in surgical diagnosis, judgment, and/or technique were the most common causes for immediate postoperative deaths. Other factors in decreasing order of frequency were the patient’s medical condition and the anesthetic technique.

Marx et al.

6 and Dripps et al.

7 independently reported that regional anesthesia was associated with a lower rate of mortality than general anesthetic techniques. In the later report by Dripps et al.,

7 deaths deemed related to spinal anesthesia occurred in 1 of 1,560 procedures, and deaths possibly related to spinal anesthesia occurred in 1 of 780 procedures. Corresponding incidences for general anesthesia were 1 of 536 and 1 of 259, respectively.

7Farrow et al.

8,

9 from Wales and Harrison

10 from South Africa independently evaluated mortality associated with surgery in the 1970s and 1980s. Farrow et al. reported that anesthesia-related mortality was highest in patients older than 65 years and anesthesia contributed to 2.2% of perioperative mortality. Harrison

10 noted that anesthesia-related deaths had significantly decreased in the later stages of their study as compared with the data gathered during the initial phases. They attributed this positive change to improvements in routine monitoring, better supervision of trainees, a decrease in caseload per anesthesiologist, and the introduction of recovery rooms and ICUs during their study period. Holland

11 from New South Wales, Australia, between 1960 and 1985 reported on deaths occurring within 24 hours of an anesthetic. The mortality rate decreased from 1 in 5,500 in the 1960s to 1 in 10,250 in the 1970s and to 1 in 26,000 in 1984. The three most common causes of death in their report were inadequate preparation of the patient and inadequate intraoperative and postoperative crisis management. The direct result of this study in Australian anesthesia practice was the phasing out of the resident medical officer as an anesthesia work force member.

Studies were also conducted during the same period in France by Tiret et al.

12 and a decade later in Finland by Tikkanen and Hovi-Viander.

13 The French study reported that respiratory depression in the postoperative period was the predominant cause of death and coma (1 in 13,207) and that major complications occurred more frequently in older patients, those with multiple comorbid conditions, and patients undergoing emergency surgical procedures. Mortality associated with anesthesia and surgery was studied in Finland in 1986 using a retrospective method, and the results were compared with those of a similar study performed in 1975. Surgery was the main contributing factor in the deaths of 22 patients (frequency 0.68/10,000 procedures) and anesthesia in the deaths of 5 patients (frequency 0.15/10,000 procedures). The role of surgery in 1986 had decreased to approximately one third and the role of anesthesia to less than one tenth as the main causes of death associated with anesthesia and surgery compared with the year 1975; in fact, 95.3% of all the patients died mainly because of coexisting medical or surgical conditions. The significant changes in anesthetic practice between the two study periods were a significant increase in specialist anesthesiologists and better recovery room and intensive care facilities.

Earlier studies of anesthetic-related mortality in the United Kingdom by Lunn et al.

14,

15,

16 led to the development of the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths (NCEPOD) in 1987.

17 All deaths that occurred within 30 days of surgery were included in the inquiry. The study categorized deaths as related to either anesthesia or surgery. There were 4,034 deaths over a 12-month period in 485,850 surgeries, leading to a crude mortality rate of 0.7% to 0.8%. Surgery contributed directly or partially to 30% of all deaths. Anesthesia was considered the sole cause of death in only 3 patients, leading to a mortality rate of 1 in 185,000, and was contributory in 410 deaths, for a rate of 7 in 10,000 cases. A striking finding of the report was that 20% of the deaths were avoidable. Avoidable factors for both anesthesiologists and surgeons were a lack of adequate trainee supervision (approximately 50% of deaths in one of the regions were those of patients who had no consultant contributing to their clinical care); failure

to act appropriately with existing knowledge (rather than lack of knowledge); equipment malfunction; and fatigue.

17 At the same time, a Canadian study reported that no deaths could be directly attributable to anesthesia.

18 Four factor groups (patient, surgical, anesthesia, and “other”) were assessed by logistic regression analysis to ascertain which variables were predictive of death within a week of surgery. Advanced age, male gender, compromised physical status, major surgery, emergency procedure, procedures performed from 1975 to 1979, intraoperative complications, narcotic techniques, and having one or two anesthetic drugs administered were associated with a higher mortality rate, whereas duration of anesthesia, experience of the anesthesiologist, and inhalation techniques did not affect the mortality rate. The authors concluded that the patient and surgical risk factors were much more important in predicting 7-day mortality than the anesthesia factors studied.

18The same authors

19 reported the results of a followup study in 27,184 anesthetic procedures performed on inpatients in four major teaching hospitals in Canada. Again, no deaths were directly attributed to anesthesia. Data on these patients were collected, and the outcomes determined for the intraoperative, immediate postanesthetic, and postoperative time periods. Logistic regression was used to control for differences in patient populations across all four hospitals. There were large variations (two-to five-fold after case-mix adjustment) in minor outcomes across the four hospitals. The rates of major events and deaths were similar in three hospitals. One of the hospitals had a significantly lower mortality rate but a significantly higher rate of all major events (cardiac arrest, MI, and stroke). Possible reasons for these differences include lack of compliance in recording events, inadequate case-mix adjustment, differences in interpretation of the variables (despite guidelines), and institutional differences in monitoring, charting, and observation protocols. The authors concluded that measuring the quality of care in anesthesia by comparing major outcomes is unsatisfactory because the contribution of anesthesia to perioperative outcomes is uncertain, and variations may be explained by institutional differences that are beyond the control of the anesthesiologist.

Warner et al.

20 studied major morbidity and mortality occurring within 1 month of ambulatory surgery in 38,598 patients and reported no deaths directly attributable to anesthesia. Fleisher et al.

21 performed a claims analysis of a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries for the years 1994 to 1999. Patients undergoing 16 different surgical procedures under anesthesia in an outpatient hospital, ambulatory surgery center, and a physician office were studied. The 7-day mortality rate was 50 per 100,000 in the outpatient hospital, 35 per 100,000 in the office setting, and 25 per 100,000 in the ambulatory surgery setting.

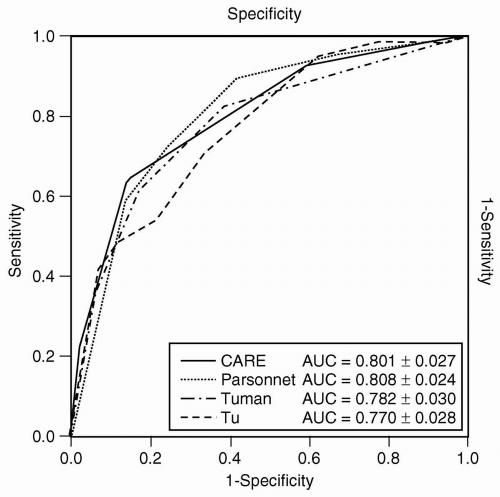

Wolters et al.

22 prospectively studied 6,304 consecutive patients admitted to surgery for perioperative complications in Germany. The objective of their study was to correlate variables recorded perioperatively with morbidity and mortality in an attempt to assess the predictive value of the variables for the outcome of individual patients. Data collected were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, emergency or elective surgery, presence of medical comorbid conditions, type of anesthesia, type of surgery, and the operating time. The surgeries were classified by the Hoehn system (commonly used in Germany) into minor, moderate, or major surgeries. Logistic regression analysis was used to study the correlation between the preoperative risk factors and postoperative complications. Within the study group of 6,304 patients, 140 died postoperatively, and 1,432 patients developed complications that they survived. The variables that had the most influence on the risk for postoperative complications were ASA class IV (odd ratio [OR], 4.2), followed by ASA class III (OR, 2.2), and severity of surgery (OR, 1.86). The model described by Wolters et al.

22 is 96% specific (able to predict uncomplicated course correctly predicted in 96% of cases) but has a very low sensitivity of only 16% (ability to correctly predict complications), giving a positive predictive value of 57% and a negative predictive value of 80%. The authors concluded that despite studying a large number of variables, they were unable to predict the risk of complications for individual patients with any degree of accuracy using statistical methods. They also implied that basing the surgical care of a patient on the probability of complications predicted by a statistical model is not any more accurate or reliable than qualified clinical judgment.

The results of a national confidential inquiry into perioperative deaths conducted in France were reported in 2004.

23 In this report, an expert committee anonymously analyzed the patients’ charts to determine the cause of death and its relation to anesthesia. The annual rates of deaths that were totally or partially related to anesthesia were 7 (95% confidence intervals [CI]; 95% CI, 2-12) and 47 (95% CI, 31-63) per million, respectively. These mortality rates increased with patient comorbidity from 4 per million in patients of ASA physical status class I to 554 per million for those in ASA class IV. Similarly, the rates increased with age from 7 per million in patients younger than 45 years to 32 per million in older patients. Accidents were of respiratory (38%), cardiac (31%), ischemic (25%), and vascular origin (30%). The main surgical procedures that contributed to the mortality were orthopedic (50%: hip fracture, hemorrhagic surgery) and colorectal (24%: occlusion, peritonitis).

Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale reported data between 1978 and 1982 on annual complications associated with anesthesia and found that 76 and 263 per million, respectively, were totally or partially related to anesthesia. The two aforementioned studies indicate that the anesthesia-related mortality rate has decreased 10-fold during the subsequent study periods, whereas the number of anesthetic procedures doubled. In addition, the number of procedures involving elderly patients and patients with poor physical status was four times higher. The authors attributed these improved results to enhanced safety and adherence to practice guidelines published after 1982. They hoped that the rate of 1 per 145,000 (at the time of publication) would serve as a basis for systematic analysis of accidents and review of future trends.

Kawashima et al.

24 reported the results of anesthesiarelated mortality and morbidity from a confidential inquiry over a 5-year period in 2,363,038 patients from Japan in 2003. Data were analyzed for the incidence of critical events during anesthesia and surgery and the outcomes of the events within 7 postoperative days. The average annual incidences of cardiac arrests during surgery due to all etiologies and totally attributable to anesthesia were 7.12 (95% CI, 6.30, 7.94) and 1.00 (95% CI, 0.88, 1.12) per 10,000 cases, respectively. The average annual mortality within 7 postoperative days due to all etiologies and that totally attributable to anesthesia were 7.18 (95% CI, 6.22, 8.13) and 0.21 (95% CI, 0.15, 0.27) per 10,000 cases, respectively. Two principal causes of cardiac arrest during anesthesia and surgery due to all etiologies were massive hemorrhage (31.9%) and surgery-related factors (30.2%); those totally attributable to anesthesia were drug overdose or selection error (15.3%) and serious dysrhythmias (13.9%). This report indicates that preventable human errors caused 53.2% of cardiac arrests, and 22.2% of those deaths in the operating room were totally attributable to anesthesia. The authors concluded that the rates of cardiac arrest and death during anesthesia and surgery due to all etiologies, as well as those totally attributable to anesthesia, were comparable to those of other developed countries.

The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) is the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care in the Veterans Administration (VA) System. Khuri et al.

25 reported the results of the first prospective multicenter study that identified the predictors of 30-day and longterm survival after major surgery, taking into account the compendium of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables that define an episode of surgical care from the NSQIP database. This study showed that events in the postoperative period are more important than preoperative patient risk factors in determining the survival after major surgery in the VA. After correcting for the confounding variables collected in the NSQIP, the occurrence of a complication within the first 30 days postoperatively, independent of the patient’s preoperative risk, reduced median patient survival by 69% in the total patient study group. This study did not focus on the role of anesthetic management in the survival rate of patients after major surgery.

The number of deaths identified each year by the NCEPOD changed little between 1989 and 2003. Successive reports showed that most deaths occur in older patients who undergo major surgery and who have severe coexisting disease.

26 A recent analysis identified higher mortality rates in a UK hospital when compared with a similar institution in the United States.

27 Pearse et al.

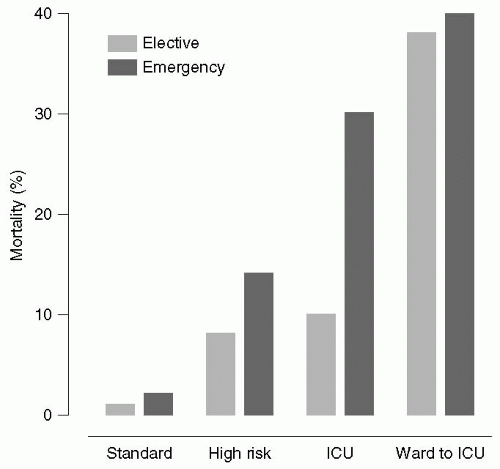

28 extracted data from the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Center (ICNARC) database and the Clinical Accountability, Service Planning and Evaluation Health Care Knowledge Systems database on inpatient general surgical procedures and ICU admissions in 94 National Health Service hospitals in the United Kingdom between January 1999 and October 2004. There were a total of 4,117,727 surgical procedures, of which a high-risk population of 513,924 patients was identified. These high-risk patients accounted for 83.8% of deaths but for only 12.5% of procedures. Despite the high mortality rates,

<15% of these patients were admitted to the ICU (see

Fig. 2.1). The authors concluded that the incidence of postoperative deaths in the United Kingdom has changed little in recent years, and that most deaths occur in older patients with coexisting medical disease who undergo major surgery. They recommended that higher ICU resources be provided for these high-risk patients.

Regional Anesthesia

Auroy et al.

29 reported the results of a 10-month prospective survey of 8,150 French anesthesiologists on major complications related to regional anesthesia based on (a) voluntary reporting during the study period using a telephone hotline service available 24 hours a day and managed by three experts; and, (b) voluntary reporting of the number and type of regional anesthesia procedures performed using pocket booklets. A total of 487 participants reported 56 major complications in 158,083 regional

anesthesia procedures (3.5 per 10,000). Four deaths were reported: three after spinal anesthesia and one after a posterior lumbar plexus block. Cardiac arrests occurred only after spinal anesthesia (

n = 10; 2.7 per 10,000) and posterior lumbar plexus block (

n = 1; 80 per 10,000). Systemic local anesthetic toxicity in all cases consisted of seizures only, without any cardiac events. Lidocaine spinal anesthesia associated with more neurologic complications than bupivacaine (14.4 per 10,000 vs. 2.2 per 10,000). Most neurologic complications were transient in nature. Among the 12 complications that occurred after peripheral nerve blocks, 9 were in patients in whom a nerve stimulator had been used.

Irita et al.

30 investigated critical incidents associated with regional anesthesia using data from annual surveys of the membership of the Japanese Society of Anesthesiologists between 1999 and 2002. The total numbers of anesthetics available for analysis were 3,855,384, of which spinal anesthesia, combined spinal-epidural anesthesia, and epidural anesthesia contributed to 409,338, 146,282, and 69,001 reviews, respectively. A total of 628 critical incidents were reported in patients receiving regional anesthesia, including 108 cardiac arrests and 45 subsequent deaths. The causes of critical incidents were classified as totally attributable to anesthetic management or due mainly to intraoperative pathologic events, preoperative complications, or surgical management. Intraoperative pathologic events consisted of coronary ischemia, including coronary vasospasm (not suspected preoperatively), dysrhythmias (including severe bradycardia), pulmonary thromboembolism, and other conditions. Mortality was defined as death within 7 postoperative days. The incidences of cardiac arrest and mortality due to all causes were 1.69 per 10,000 and 0.76 per 10,000 with spinal anesthesia, 1.78 per 10,000 and 0.68 per 10,000 with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia, and 1.88 per 10,000 and 0.58 per 10,000 with epidural anesthesia, respectively. The incidences of cardiac arrest and mortality due to anesthetic management were 0.54 per 10,000 and 0.02 per 10,000 with spinal anesthesia, 0.55 per 10,000 and 0.00 per 10,000 with combined spinalepidural anesthesia, and 0.72 per 10,000 and 0.14 per 10,000 with epidural anesthesia, respectively. These values did not significantly differ between the three regional anesthesia groups. Intraoperative pathologic events and anesthetic management were responsible for 43% and 33% of cardiac arrests, respectively. Among the causes of anesthetic management-induced critical incidents, inadvertent high spinal anesthesia was the leading cause of cardiac arrest in both spinal and combined spinal-epidural anesthesia groups. Ninety percent of cardiac arrests occurred in patients with ASA physical status I and II, 88% in patients below 65 years of age, 45% in patients undergoing hip or lower extremity surgery, and 25% in patients undergoing cesarean section. The authors concluded that the incidence of cardiac arrest and mortality associated with central neuraxial anesthesia in Japan was similar to that of other developed countries. In patients with good ASA physical status, critical incidents occurred more often under regional anesthesia than under general anesthesia.