Chapter 1 Essential Components for a Patient Safety Strategy

The safety of operating rooms depends largely on the professional and regulatory requirements that mandate skill levels, documentation standards, appropriate monitoring, and well-maintained equipment. Prescriptive and detailed protocols exist for almost every procedure performed, and although variation based on surgical and anesthesia preference is allowed, overall there is excellent management of the technical aspects. Experienced operating room physicians, nurses, and technicians come to rely on these operating room characteristics to support the delivery of safe care. Most practitioners, however, at some time have had the experience of working in suboptimal operating room conditions. This may be attributed to the level of procedural complexity in even the simplest of operative procedures when the level of complexity is not matched by the necessary team coordination, leadership engagement, or departmental perspective that encompasses all the prerequisites for reliable delivery of care. There are many causes for this current state, which include, depending on the country, the mechanisms for reimbursement that impede alignment of interests between physicians and hospitals (Ginsburg et al, 2007); the limited interdisciplinary training of the various disciplines (i.e., surgery, anesthesia, nursing, and technician), which promotes a hierarchical structure and undervalues core team characteristics; and the historical perceptions about the roles of physicians, nurses, and ancillary personnel, which have not kept pace with the changing nature of current health care delivery (Baker et al, 2005).

As far back as 1909, Ernest Avery Codman, a Boston orthopedic surgeon, openly challenged the then-current orthodoxy and proposed that Boston hospitals and physicians publicly share their clinical outcomes, complications, and harm. Wisely, he resigned his hospital position shortly before going public with this request, so he could not be thrown off the staff. Despite that, criticisms of him and his ideas were severe. Today his wishes are being realized across the United States at a rapidly accelerating pace (Mallon, 2000). The 1991 Harvard Practice Study, which evaluated errors in 30 hospitals in New York State, ultimately led to the now highly quoted number of 98,000 unnecessary deaths per year attributed to health care error. The Harvard Practice Study forced the health care industry to reflect on problems in patient care resulting in patient harm (Brennan et al, 1991; Leape et al, 1991). From these reflections a science of comprehensive patient safety has developed from disciplines such as engineering, cognitive psychology, and sociology. Combined with the increasing pace of electronic health record deployment, the movement toward demonstrable quality and value in medical care is advancing quickly.

THE CASE FOR SAFE AND RELIABLE HEALTH CARE

The 1991 Harvard Practice Study was the seminal article leading to the 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, To Err Is Human (Kohn et al, 2000), and that report has led to great public and business awareness of quality and safety problems in the health care industry. The media have fueled the public’s interest, and businesses have formed advocacy groups, such as Leapfrog (Delbanco, 2004), to focus attention on this critical topic. The U.S. government program Medicare, with approximately $600 billion in annual spending, recently announced it would not pay for care resulting from medical errors (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2008). Large private insurers are quickly following suit. Aetna just announced it will not pay for care related to the 28 “never events” defined by the National Quality Forum (Aetna Won’t Pay, 2008).

Rapidly developing transparency in the market about safety and quality will be a major driver in health care change. Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital in Boston posts its quality measures on its Web site, including its recent Joint Commission accreditation survey (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 2008). New York Health and Hospitals, the largest public care system in the United States, has committed to following this example. The State of Minnesota publicly posts on the Internet all its hospitals’ reported never events, such as wrong site surgeries and retained foreign objects during surgery (MDH Division of Health Policy, 2008). Several other states are quickly emulating this practice. Geisinger Clinic in Pennsylvania now offers a warranty on heart surgery (Ableson, 2007), in which specified complications are cared for without charge. Given the impressive care processes they have developed, this is a logical way to communicate their superior care and compete in the market. The successful hospitals and health systems in this new rapidly transparent market will be the ones that apply systematic solutions to enhance patient safety. Other bright spots in the systematic approaches taken by large care systems include Kaiser Permanente and Ascension in the areas of surgical and obstetric safety and through Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) initiatives, such as the 100,000 Lives Campaign and the 5 Million Lives Campaign (IHI, 2008).

THE OPERATING ROOM AS A SYSTEM

• The reliability of achieving the desired outcome not just once but repeatedly

• Evaluating the processes leading to the desired outcome

• Analyzing in detail the indivisible steps that make up the process

ACHIEVING RELIABILITY IN SYSTEMS

Operating rooms have done a remarkably good job of making themselves reliable and safe, albeit in a health care industry that has been slow to incorporate many key features of reliable systems (Cooper and Gaba, 2002). The Harvard anesthesia practice standards (Eichhorn et al, 1988), generated in the 1980s and adopted across the United States, are a shining example of standardization of anesthesia care that has helped improve the safety of the specialty. These standards identified minimum monitoring expectations now commonly used in every surgical procedure. They affect all of perioperative nursing and influenced the broad adoption of pulse oximetry and capnography.

Reliability is feasible only when six interdependent factors are effectively integrated (Leonard et al, 2004a):

• An environment of continuous learning

• A just and fair culture (Marx 2001; Marx, 2003)

• An environment of enthusiasm for teamwork

• Leaders who are engaged in safety and reliability through the use of data (Frankel et al, 2003; Frankel et al, 2005)

• Effective flow of information

Integration occurs only through concerted effort at multiple levels, starting with a goal, which takes precedence over all others, to achieve reliability. Organizations and departments that pursue greater reliability find that the end result positively influences patient care and employee satisfaction (Yates et al, 2004); it is obvious even to outside observers. To some extent this applies to all operating room practitioners as they arrive in a location to participate in a procedure. The initial reaction, that gut feeling about the quality of relationships and the safety of the environment, should be taken seriously, for it is likely to be a good barometer of the risk inherent in the environment (CMS, 2008).

AN ENVIRONMENT OF CONTINUOUS LEARNING

One example of a paradigm for a learning environment is Toyota Industries. It leads the auto industry in size and sales, and the enthusiasm of its car owners is well known. Toyota employees make suggestions for improving the work they do an average of 46 times per year and do so with the knowledge that a significant number of their suggestions will be tested and, if found worthy, adopted and spread. This process of applying the insights of the frontline workers to change and improvement applies not only to the production of Toyota’s cars but also to the fundamental work of improvement itself (Spear, 2004). If a change in a procedure takes 1 month today, Toyota would be seeking ideas so that a year from now it could perform that change in 3 weeks. If Toyota receives 10 useful suggestions daily from a department, then 1 year from now its goal would be to receive 12 or 15. Toyota’s perspective is that improvement is always feasible and there is always waste to be removed from its processes. The fact that in a prior quarter wasted effort and materials decreased as a result of focused improvement efforts is immaterial. There is, unrelentingly, always more to be achieved (Liker, 2004; Liker and Hoseus, 2008).

For decades, physicians and hospitals have had a guild relationship in which single physicians plied their trade within the walls of a hospital but with singularly insular perspectives. In the past 20 years a different health care industry has begun to emerge, built on a flood of hard evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials. Groups of clinicians are now providing service-line delivery across the spectrum of care-associated specific diseases (Ableson, 2007).

An environment of continuous learning in health care requires the presence of certain structural elements and the ability to execute ideas. The most basic structural element is the meeting of the clinical, unit-based leadership to consider information about unreliable events and decide on actions to remedy them (Mohr and Batalden, 2002). Surgical procedures will take place safely only in those clinical units whose leaders are able to orchestrate this process. Nursing must be an integral part of the leadership discussions in that unit. Multidisciplinary staff should meet on a regular basis to examine the straightforward operational issues in units, from items as specific as getting drugs to the right places in each room to the flow of patients through the entire suite.

The information collected at such meetings should be collated and evaluated so that remedies to any problems, potential problems, or concerns may be pursued. As in other industries with reputations for high reliability (Freiberg and Freiberg, 1998), listening to the front line and acting on their concerns is key to ensuring a safe process. This requires an environment or culture that makes it easy to bring problems to light and a teamwork structure that supports this process.

A JUST AND FAIR CULTURE

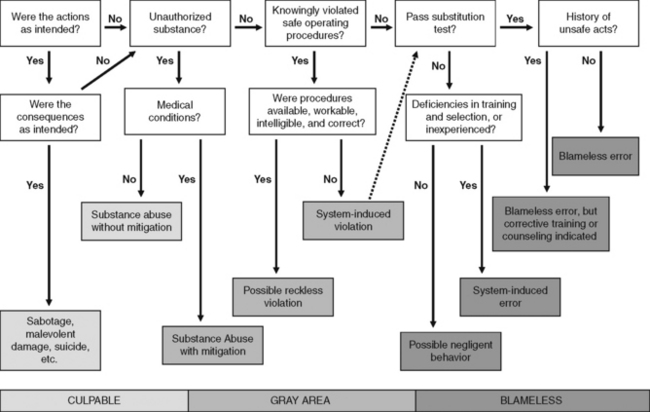

A just and fair culture in health care is one in which individuals fully appreciate that, although they are accountable for their actions, they will not be held accountable for system flaws (Reason, 1997; Marx, 2001). This culture provides a framework for looking at errors and adverse events to quickly and consistently determine if an individual nurse or physician involved in the event has behavioral or technical skill problems, whether or not he or she was set to fail by system flaw. This means evaluating the culpability of an individual after an error, accident, or adverse event by using a simple algorithm (Figure 1-1) that asks the following (Reason, 1997):

• Did the individual mean to cause harm?

• Did the individual come to work impaired (by drugs, alcohol, and so forth)?

• Did the individual follow reasonable rules that others who have similar knowledge and skills would have followed?

• Did the individual have a history of participating in or causing unsafe acts?

Figure 1-1 Reason’s Simple Algorithm.

(From Reason JT: Managing the risks of organizational accidents, Aldershot, Hampshire, England, and Brookfield, Vt, 1997, Ashgate.)

Tragic examples highlight the need for this objective and clear evaluation mechanism, such as the overdoses in Indianapolis in 2006 of the blood thinner heparin. After the wrong concentration of heparin, 100 times too concentrated, was put in the automated pharmacy dispensing machine, nine very skilled individuals—six newborn intensive care unit nurses and three neonatologists—mistakenly took the wrong concentration of drug and administered it to very small infants. Three fatalities resulted (WRTV, 2008).

A similar episode occurred in 2007 involving the actor Dennis Quaid and his family in Los Angeles (Fox News, 2008). The media coverage of the Quaids’ cases has highlighted their trauma as patients and the outrage that occurs when patients feel they are not being told the truth. Missing are the processes required to identify the underlying causes and fixes of these errors. They require an engineering and systematic approach that begins with an objective view of the events and from which flow insights about systematic flaws and individual culpability.

Thought leaders on both sides of the Atlantic have developed schema to address this topic. James Reason in the 1990s described his incident analysis tree (Reason, 1997). In the past decade David Marx developed his Just Culture Algorithm for evaluating the choices made by frontline providers, which incorporates and expands on Reason’s work. In both cases the goal is to ensure appropriate accountability and an environment where every decision made by senior leadership and middle management is based on integrity and ethics.

THE GOOD HEALTH CARE TEAM

What is a good health care team? A good team is a group of interdependent individuals who have the following characteristics (Hackman, 1990; Pryor et al, 2006):

• They have diverse skills and share a common goal.

• Their output through synergy is greater than the sum of the individuals within the group.

• They have an appreciation of the roles played by each team member, including the leaders.

• They know each other’s expertise so well that team members know where to turn to solve a problem.

• They have each agreed individually on norms of conduct, one of which is nonnegotiable mutual respect.

• They address technical problems directly using the skill mix of the team but face complex problems that require adaptation and flexibility through collaboration and open discussion.

• Individuals may express concerns without fear of retribution and know that their concerns will engender only two possible responses: their concerns will be acted on, or knowledge will be respectfully brought to light that mitigates the concern.

TEAM LEADERS: THE CRITICAL ROLE OF LEADERSHIP

The active and committed engagement of executive and clinical leaders in systematically improving safety and quality is essential. One of the greatest challenges is aligning the frequently large number of strategic priorities in an organization with a simple, focused message that resonates with frontline clinicians caring for patients. Alignment and clarity of an organization’s patient safety goals and work is critical. Senior leaders need to clearly communicate the priority of safe and reliable care and model these behaviors on a daily basis. Effective leaders continually reinforce the values and “this is the way we provide care within our organization.” Excellent examples of how to do this well come from (1) the communication at Ascension Healthcare to everyone working in their 71 hospitals: “Care that’s safe, care that’s right, and then we’ll have the resources to take care of the people with no care” (Pryor, 2006), and (2) the long-standing Mayo Clinic motto that goes back to Dr. Mayo himself, “Always in the patient’s best interests” (Davidson, 2002).

Leaders also are keepers and drivers of organizational culture. Setting the tone of how the organization values its people—how it treats them and expects them to treat each other—is at the core of organizational excellence, or the lack thereof. The presence of overt disrespect is extremely destructive within a culture. Unfortunately, this behavior is pervasive in most health care systems and creates unacceptable risk, because nurses may be hesitant to call certain physicians with patient concerns because of the way they have been treated in the past. Sadly, hesitancy to voice a concern or approach certain individuals is a common factor in serious episodes of avoidable patient harm (Leonard et al, 2004a). Encouragingly, a growing list of leaders and hospitals are now dealing directly with this issue. If they do not, they pay with increased nursing turnover, poorer patient satisfaction, and increased clinical risk.

Team leadership is not an innate skill; it is learned (Heifetz, 1994). Physicians are by definition most frequently the leaders of their teams, and nowhere is this truer than in the environments where surgery is performed. Equally true, however, is that the best decisions about direction and goals—those decisions that are most likely to support reliability and safety—accrue from leadership shared among surgeon, anesthesiologist, nursing, and other team members and are feasible only with forethought, discussion about agreed-on norms of behavior, and practice.

Briefing

Briefings in operating rooms are multistep affairs, ideally beginning with a gathering of the surgical team with the patient in the preoperative area and a discussion that engages the patient and team members in delineating a plan for that procedure. The briefing process might continue after the patient is sedated or asleep in the operating room, at which point a further briefing might ensue about any issues that team members might consider unsettling. These might include, for example, concerns about equipment logistics or a team member’s personal comments about what he or she believes are his or her limitations that day, stated as a request that other team members work more closely with him or her. In the United States a third part of the briefing process occurs just before incision and is the time-out. This is a regulatory requirement by The Joint Commission (2003) to ensure correct laterality of the procedure and identification of the patient and procedure.

A good initial briefing process has four components in which leaders do the following:

• Ensure that all team members know the plan.

• Assure team members they are operating in an environment of psychological safety (Bohmer and Edmondson, 2001; Roberto et al, 2006) where they may be completely comfortable speaking up about their concerns.

• Remind team members of agreed-on norms of conduct (Hackman, 1990) such as specific forms of communication that increase the likelihood of accurate transmission and reception of information.

• Expect excellence and excellent performance (Collins, 2001), reminding team members of their responsibility to do their best and remain, throughout, engaged in the performance of the team activity and centered on the plan and team goals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree