ENT EMERGENCIES

JOEL D. HUDGINS, MD AND GI SOO LEE, MD, EdM

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

The ear, nose, and throat are common sites for infection and neoplasms and may be the sources of acute pain. Although the diseases prompting the emergency department (ED) visit may be distressing to the patient and cause considerable anxiety for the parents, they are rarely life-threatening. The goals of care include rapid recognition of the rare surgical and infectious emergencies and obtaining a thorough evaluation.

KEY POINTS

New trends in treatment of otitis media center around the age of the patient and the severity of illness. Empiric treatment with antibiotics is not always warranted as this process is often self-resolving and rarely leads to complications.

New trends in treatment of otitis media center around the age of the patient and the severity of illness. Empiric treatment with antibiotics is not always warranted as this process is often self-resolving and rarely leads to complications.

Intracranial complications of sinusitis are associated with fever, headache, vomiting, and change in mental status.

Intracranial complications of sinusitis are associated with fever, headache, vomiting, and change in mental status.

CT scans with contrast are the diagnostic test of choice to diagnose retropharyngeal abscess.

CT scans with contrast are the diagnostic test of choice to diagnose retropharyngeal abscess.

Life-threatening etiologies of vertigo are commonly associated with hearing loss.

Life-threatening etiologies of vertigo are commonly associated with hearing loss.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Dizziness and Vertigo: Chapter 19

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Neurologic Emergencies: Chapter 105

ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

Goals of Treatment

Otalgia is an exceedingly common complaint in the emergency department. Providing symptomatic relief to these patients should be a priority. Given that many cases of otitis media are viral in nature, it is important to discern which cases warrant antibiotic therapy. Judicious but appropriate antibiotic therapy may shorten duration of illness in some cases and can prevent complications such as mastoiditis, meningitis, and facial nerve paralysis.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Children greater than 2 years of age without severe otitis media can be observed off antibiotics

• Facial nerve palsies should prompt a thorough evaluation of the middle ear

• Young children with cochlear implants are at significantly increased risk of pneumococcal meningitis secondary to acute otitis media

Current Evidence

Apart from viral infections of the upper respiratory tract, acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common head and neck infection in children and is the second most common diagnosis made in the emergency department (ED). It may occur as an isolated infection though it is commonly a complication of an upper respiratory tract infection. Children with noninfected fluid in the middle ear (also called otitis media with effusion [OME] or serous otitis media or secretory otitis media) are at increased risk for acute otitis media. Other risk factors include: day care attendance, exposure to secondhand smoke, and immunodeficiency states.

In addition to viral etiologies, the more common organisms causing acute otitis at all ages are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Group A β-hemolytic streptococci is a less common etiology. Other Gram-negative organisms may occur in hospitalized patients who are younger than 8 weeks or immunosuppressed.

Over the last decade, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Joint Committee of American Academy of Family Practitioners (AAFP) have developed guidelines to improve accuracy of diagnosis of AOM which were last modified in 2013. Based on the best available evidence in the literature, diagnosis of AOM can be made based on the presence of any one of the following three criteria:

1. Moderate to severe bulging of tympanic membrane

2. Acute onset otorrhea not due to otitis externa

3. Mild bulging and >48 hours of ear pain or intense erythema of tympanic membrane (TM)

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

AOM should be suspected in any child who is irritable or lethargic, has a low-grade fever, and has localized pain in the ear. Older children may have rapid onset of severe ear pain. However, younger patients may rub, tug, or hold the ear as a sign of otalgia. Spontaneous perforation of the TM with serosanguineous drainage may occur in less than 1 hour after the onset of pain. On examination, the TM is hyperemic and mobility is decreased. The strongest predictor of AOM is the presence of a bulging TM that obliterates normal landmarks, whereas isolated hyperemia is least helpful in predicting the disease. Infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and other bacteria may cause blebs on the lateral surface of the drum. The vesicles of bullous myringitis are filled with clear fluid and are painful. The appearance of the TM in AOM secondary to bacterial pathogens does not differ significantly from AOM of viral etiology.

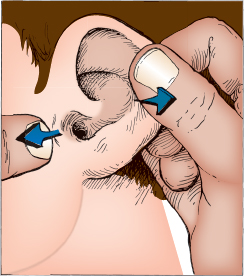

FIGURE 126.1 The external meatus is opened by pulling the auricle in the posterior-superior direction and placing traction on the skin immediately in front of the tragus.

Triage Considerations

Children with altered mental status, high fevers, extreme pain, severe headache, or neurologic abnormalities should be evaluated promptly for complications associated with otitis. Meningitis and intracranial abscesses are rare complications of otitis media.

Clinical Assessment

Acute otitis media should be suspected in any patient with low-grade fevers, ear pain, and irritability. Presentation may vary according to age, as younger patients tend to present with less-specific symptoms such as decreased oral intake and irritability, while pulling at the affected ear. Older children can typically describe otalgia.

Alternative diagnoses such as a foreign body, middle ear effusion, and otitis externa should be considered and considered during the history. A recent history of swimming or pain externally should point the clinician toward a diagnosis of otitis externa.

Examination of the ear begins by inspection of the auricle and surrounding areas. The external meatus should be visualized directly with a bright light after it is fully opened by pulling the pinna posteriorly and superiorly. The tragus may be displaced forward by traction on the skin in front of the ear with the examiner’s other hand (Fig. 126.1). The ear canal can then be examined with a pneumatic otoscope, using the largest speculum that will fit in the meatus without discomfort. Wax or debris occluding the ear canal should be removed with a curette or by repeated irrigation with body-temperature water (see Chapter 141 Procedures, section on Cerumen Removal). Irrigation of the canal should not be performed if a ventilating tube is in place or if a perforation of the tympanic membrane (TM) is suspected.

The TM should be evaluated for its appearance, and part of the middle ear contents can usually be seen if the eardrum is translucent (Fig. 126.2) (see also Fig. 53.2). Mobility should be evaluated with the pneumatic otoscope rather than visualization alone, as this can increase the accuracy of diagnosing middle ear pathology. Pneumatic otoscopy is performed by applying positive and negative pressure to the TM, with the pneumatic otoscope fitted snugly into the ear canal. The pressure applied to the ear can be varied by squeezing a rubber bulb (see Chapter 141 Procedures, section on Pneumatic Otoscopic Examination). Middle ear effusion is more likely to be present if the TM fails to move with this technique.

FIGURE 126.2 Right tympanic membrane.

The ear of a neonate requires special attention to perform an adequate otologic examination. The ear canal itself is narrow and collapsible. Often, only the otoscopic speculum can be inserted, as positive pressure from the pneumatic bulb is used to distend the canal ahead of the advancing speculum. The canal may be filled with vernix caseosa, which must be removed or irrigated out of the canal to permit visualization of the TM. The neonate’s TM lies at a more oblique angle to the ear canal (compared with older children) and may make recognition of the TM and its landmarks more difficult. Amniotic fluid may be present in the middle ear cavity for days to weeks after birth and should not be confused with middle ear infection unless other symptoms such as fever and irritability are present.

A variety of scoring systems have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of AOM, though none have been formally recommended by the AAP.

Management

The clinical diagnosis of AOM is made clinically and no additional laboratory or imaging studies are necessary. Antibiotics prescribed for AOM account for 25% to 50% of all outpatient antibiotics and are partly responsible for the global finding that bacteria, especially S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis, are becoming increasingly resistant to these medications. As such, expert panels and various medical societies have examined the benefits and choice of antibiotics used for this disease. The AAP/AAFP guidelines stress the need to improve accuracy of diagnosis and to use antibiotics judiciously in treating AOM. Using the best available literature, including randomized clinical trials and cohort studies of patients with suspected AOM treated with antibiotics versus those treated with observation, the AAP/AAFP panel concluded that 80% of children who were not treated with antibiotics had spontaneous resolution of symptoms within a 2- to 7-day onset of symptoms. With this information, the panel suggested that a period of observation might be appropriate for otherwise healthy patients with AOM. However, very young children, those with immune, genetic, or craniofacial anomalies, known or underlying OME, or recent AOM in the previous 30 days should not be considered candidates for this option because they are more likely to suffer adverse consequences from observation alone. The panel also specified that the observation option must be used only if there is a high probability that the parent will be compliant in returning for evaluation if symptoms of AOM persist over the next 72 hours.

Specific recommendations therefore vary by age and severity of illness. Any patient younger than 6 months should be treated with antibiotics. The observation option is recommended for children 6 months to 2 years of age whose baseline health is good and who are not ill at presentation without evidence of severe disease. The option of observation is available for children older than 2 years, with nonsevere illness at presentation (Table 126.1). In prospective studies, 25% of those children did eventually require antibiotic upon follow-up within 48 to 72 hours. With regard to follow-up, the guidelines suggest that the observed patients be contacted or seen within 72 hours so that they may be treated if symptoms persist. Other authors have advocated writing a “safety net prescription” to be given to parents of children who are observed at the time of the initial assessment with instructions to fill it if symptoms persist.

TABLE 126.1

OPTIONS FOR THE TREATMENT OF ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA (AAP/AAFP) GUIDELINES

Guidelines for intervention for persistent or recurrent AOM vary. Patients with multiple episodes of AOM over a period of months, OME lasting more than 6 to 8 weeks, complications of middle ear disease, or associated hearing or speech concerns should be referred to an otolaryngologist for evaluation for possible surgical treatment (myringotomy and tube placement).

To effectively treat AOM, the most important pathogen to address is S. pneumoniae because it is less likely to resolve spontaneously without treatment compared with H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. Although a large number of species exist that are resistant to amoxicillin and cephalosporins, evidence from the literature and guidelines suggest that no antibiotic outperforms amoxicillin as the first-line drug to treat AOM in patients who are not allergic to penicillin. Higher dose amoxicillin (80 to 90 mg/kg/day) in two divided doses for 5 to 10 days has been shown to be more effective than standard dosing (40 mg/kg/day) in that it overcomes the minimum inhibitory concentrations of penicillin to kill intermediate and some highly resistant strains of S. pneumoniae. Initial therapy in uncomplicated AOM in patients who have type 1 hypersensitivity (anaphylaxis or history of hives) to penicillin should be treated with a cephalosporin. Those with have similar reaction to cephalosporins should be treated with a macrolide or possibly clindamycin.

In general, if symptoms persist after a child has taken first-line antibiotics for 48 to 72 hours, then the child should be re-evaluated by a health care provider (either by phone or in the office). Antibiotics should then be prescribed to cover β-lactam producing organisms. Specifically, amoxicillin-clavulanate (90 mg/kg/day in twice a day dosing, using the 600 mg per 5 ml suspension) is recommended. Other options include oral cefdinir, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime and, less commonly, ceftriaxone in IV (intravenous) or intramuscular dosing.

Pain should be controlled with acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Oral opiates should be limited to use in those with severe pain. Topical benzocaine (Auralgan or Americaine Otic) provides additional, but brief (30 to 60 minutes), relief for some children but should not be used in patients who have TM perforations or ear tubes. Antihistamines, decongestants, and corticosteroids have shown only minimal benefit and are not recommended.

Rarely, complications of AOM may be encountered in the ED. The following changes may be noted to the TM or the middle ear:

The purulent exudate that fills the middle ear space causes a conductive hearing loss. The congealed exudate may organize and stimulate hyalinization and calcification, leading to myringosclerosis (white patches within the TM) and sometimes tympanosclerosis (white deposits in the middle ear).

The purulent exudate that fills the middle ear space causes a conductive hearing loss. The congealed exudate may organize and stimulate hyalinization and calcification, leading to myringosclerosis (white patches within the TM) and sometimes tympanosclerosis (white deposits in the middle ear).

Spontaneous perforation of the TM usually produces a small hole that heals rapidly; however, large perforations may occur that do not heal even after the infection has cleared.

Spontaneous perforation of the TM usually produces a small hole that heals rapidly; however, large perforations may occur that do not heal even after the infection has cleared.

Ossicular necrosis may also occur in children who have had AOM or OME and can cause a persistent conductive hearing loss. The distal tip of the incus is most susceptible to erosion that can cause eventual disconnection of the incus from the stapes, resulting in conductive hearing loss.

Ossicular necrosis may also occur in children who have had AOM or OME and can cause a persistent conductive hearing loss. The distal tip of the incus is most susceptible to erosion that can cause eventual disconnection of the incus from the stapes, resulting in conductive hearing loss.

As the TM heals after a perforation, skin from the lateral surface of the TM may be trapped in the middle ear to form a cyst (cholesteatoma) that can expand and destroy the structures of the middle ear and surrounding bone.

As the TM heals after a perforation, skin from the lateral surface of the TM may be trapped in the middle ear to form a cyst (cholesteatoma) that can expand and destroy the structures of the middle ear and surrounding bone.

AOM may cause inflammation in the inner ear (serous labyrinthitis). This causes mild to moderate vertigo without a sensorineural hearing loss.

AOM may cause inflammation in the inner ear (serous labyrinthitis). This causes mild to moderate vertigo without a sensorineural hearing loss.

Any of these findings warrant consultation with an otolaryngologist to determine the need for acute intervention, or if the patient can be safely discharged to specialty follow-up as an outpatient.

Other complications warrant more acute intervention and urgent otolaryngology consultation:

Facial nerve paralysis may occur suddenly during AOM. The nerve paralysis may be partial or complete when the child is first examined. The facial nerve usually recovers complete function if appropriate systemic (IV followed by oral) antibiotic therapy is administered and a wide myringotomy with or without tube placement for drainage is carried out as soon as possible.

Facial nerve paralysis may occur suddenly during AOM. The nerve paralysis may be partial or complete when the child is first examined. The facial nerve usually recovers complete function if appropriate systemic (IV followed by oral) antibiotic therapy is administered and a wide myringotomy with or without tube placement for drainage is carried out as soon as possible.

Bacterial invasion of the inner ear (suppurative labyrinthitis) causes severe sensorineural hearing loss and severe vertigo that is usually associated with nausea and vomiting. Early treatment with IV antibiotics and wide myringotomy with tube placement may prevent permanent inner ear damage.

Bacterial invasion of the inner ear (suppurative labyrinthitis) causes severe sensorineural hearing loss and severe vertigo that is usually associated with nausea and vomiting. Early treatment with IV antibiotics and wide myringotomy with tube placement may prevent permanent inner ear damage.

Suppurative mastoiditis (acute coalescent mastoid osteomyelitis) may develop, causing destruction of the mastoid air cell system. Temporal bone computed tomographic (CT) scans are helpful in differentiating otitis media from mastoiditis. Patients with otitis media or mastoiditis have opacified mastoid air cells when disease is present, but those with mastoiditis also have radiographic evidence of erosion of the mastoid air cells creating larger opacified spaces. As the infection spreads to the postauricular tissues, subperiosteal collection of purulent material displaces the auricle inferolaterally from its normal position. The pus may extend through air cells to the petrous portion of the temporal bone, causing a constellation of symptoms of diplopia (sixth cranial nerve palsy), severe ocular pain, and otorrhea; this trifecta is known as Gradenigo syndrome). Pus may also break through the mastoid tip, extend into the upper neck, and create a Bezold abscess.

Suppurative mastoiditis (acute coalescent mastoid osteomyelitis) may develop, causing destruction of the mastoid air cell system. Temporal bone computed tomographic (CT) scans are helpful in differentiating otitis media from mastoiditis. Patients with otitis media or mastoiditis have opacified mastoid air cells when disease is present, but those with mastoiditis also have radiographic evidence of erosion of the mastoid air cells creating larger opacified spaces. As the infection spreads to the postauricular tissues, subperiosteal collection of purulent material displaces the auricle inferolaterally from its normal position. The pus may extend through air cells to the petrous portion of the temporal bone, causing a constellation of symptoms of diplopia (sixth cranial nerve palsy), severe ocular pain, and otorrhea; this trifecta is known as Gradenigo syndrome). Pus may also break through the mastoid tip, extend into the upper neck, and create a Bezold abscess.

The most common intracranial problem associated with AOM is meningitis, which may cause severe sensorineural deafness and irreversible vestibular damage. Less commonly associated problems are cerebritis, epidural abscess, brain abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis, and otitic hydrocephalus. The child with overt or impending intracranial complications should be stabilized, be given IV antibiotics, and have a CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed.

The most common intracranial problem associated with AOM is meningitis, which may cause severe sensorineural deafness and irreversible vestibular damage. Less commonly associated problems are cerebritis, epidural abscess, brain abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis, and otitic hydrocephalus. The child with overt or impending intracranial complications should be stabilized, be given IV antibiotics, and have a CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed.

SINUSITIS

Goals of Treatment

The common cold and upper respiratory tract infection accounts for the majority of infections of the nose and paranasal sinuses. However, bacterial infection of the sinuses is a more serious condition that requires careful examination and prompt treatment. Differentiating bacterial from viral infections can be difficult but is an important aspect of treatment. Severe complications can also result from untreated acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABR), including orbital cellulitis, intracranial abscess, and meningitis. Preventing these life-threatening complications as well as prompt recognition and treatment when they do occur are important goals of treatment.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Imaging studies are not indicated for uncomplicated acute bacterial sinusitis

• Persistence of symptoms longer than 10 days can help differentiate between bacterial sinusitis and viral upper respiratory infection

• Amoxicillin-clavulanate is an appropriate first line choice for oral antibiotic therapy in acute bacterial sinusitis

Current Evidence

Between 5% and 7% of viral upper respiratory infections are complicated by the development of secondary bacterial rhinosinusitis. Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis should be suspected when cough, halitosis, low-grade fever, and purulent rhinorrhea are present. Symptoms such as headache and facial pain may be present, but are variable, particularly in younger patients. Bacterial infection is also more likely to be present when the nasal discharge lasts more than 10 days and if the color of the discharge is thick yellow or green. Sinus imaging in uncomplicated ABR is not recommended, given the potential for false positive studies and risk of radiation exposure. Complications of ABR are estimated to occur in approximately 5% of hospitalized patients, and are a result of extension of the infection into either the orbital or intracranial space.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

There is considerable overlap between the clinical manifestations of ABR and viral upper respiratory infections. Children will often present with cough, nasal symptoms, fever, and headache in both viral upper respiratory infections as well as ABR. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends a presumptive diagnosis of ABR in patients with acute upper respiratory infections with any one of the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree