Chapter 17 End-of-Life Issues for Emergency Nurses

The trend toward offering patients in-home palliative care earlier in the end-of-life process is having an impact on how patients die in today’s society. Palliative care focuses on the physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and existential needs of the patient and family. The goal of palliative care is to help the patient achieve the best quality of life by relieving uncomfortable symptoms while respecting religious and cultural practices.1 Palliative care is often provided through hospice services or palliative care services. Nonetheless, emergency providers still have many opportunities to improve care by helping to provide a dignified end of life for patients and their families and supporting cultural and religious practices.2

End-of-Life Decisions

Advance Directives

• An advance directive may include a living will or health care proxy and is based on the belief that patients have a right to make their own treatment decisions.

• An advance directive is not the equivalent of a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order.

• The purpose of an advance directive is to encourage patients and their families (or significant others) to understand, reflect on, and discuss desired treatment options before the need for resuscitation or other emergency interventions.3

• Although state law (usually a Natural Death Act) is the legal basis for advance directives, laws differ in respect to format, forms, witness requirements, and the need for a notary public.

• A living will allows individuals to specify whether they would accept or refuse particular life-sustaining interventions such as dialysis, mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), tube feeding, intravenous (IV) hydration, and blood transfusions.4

• A health care proxy (or durable power of attorney for health care) identifies a specific individual who can make medical decisions on behalf of the patient once the patient is unable to make decisions for himself or herself.1

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 is a federal law that requires all health care agencies that receive federal funding to recognize advance directives. Under the law, hospitals must do the following:5

• Ask patients if they have an advance directive.

• Offer patients and families information about advance directives.

• Inform patients of state laws that pertain to advance directives.

• Notify patients about any hospital policies that affect advance directives.

• Most hospitals attempt to honor a patient’s wishes, but specific exceptions may exist and institutional policies must identify these situations clearly.

• In the event that a health care provider is not willing or able to honor an advance directive, the provider should inform the patient and family of this and arrange for transfer of care to a new practitioner.

• Hospitals need a clear method for identifying patients with advance directives and must have a plan for making these documents readily available to guide treatment decisions.

• In some situations, consultation with the ethics committee for the hospital can guide care decisions. Unfortunately, ethics committee consultations are usually difficult or impossible in emergent situations.

• Potential problems should be identified proactively and addressed with any patient nearing the end of life who uses the ED frequently.

• Consult the ethics committee or risk management department if there appears to be a misunderstanding or disagreement about patient preferences and treatment options.

Table 17-1 provides a list of Internet resources related to advance directives.

TABLE 17-1 INTERNET RESOURCES RELATED TO ADVANCE DIRECTIVES

| ORGANIZATION OR GROUP | INTERNET ADDRESS |

|---|---|

| American Association of Retired Persons | http://www.aarp.org/index.html |

| Aging with Dignity—Five Wishes | http://www.agingwithdignity.org/5wishes.html |

| American Bar Association (ABA Network) | http://www.abanet.org/home.cfm |

| American Medical Association | http://www.ama-assn.org |

| Compassion & Choices | http://www.compassionandchoices.org |

Out-of-Hospital Do Not Resuscitate Orders

• If an individual with an out-of-hospital DNR order experiences a cardiac or respiratory arrest, emergency medical services personnel should not initiate CPR. However, they can provide the following:

• Some states limit access to out-of-hospital DNR orders to patients who are terminally ill or elderly, whereas other states make them available to any competent adult.

• To be valid, an out-of-hospital DNR order requires the health care provider’s signature and the patient’s or surrogate’s signature.

• To avoid potential confusion, patients should have a copy of the original order and some form of wearable identification such as a medical alert bracelet.

• Most states include a provision allowing emergency medical services personnel to perform CPR if the family persistently and strongly requests it, even if the patient has an out-of-hospital DNR order. However, in these difficult situations, emergency medical services personnel are trained to counsel families to forgo CPR.

• Ideally, medical facilities will have a policy that defines the circumstances under which an out-of-hospital DNR order will be honored within the health care facility. These policies should address care of the person with an out-of-hospital DNR in the ED, clinic, or inpatient setting. In addition, discussion regarding out-of-hospital DNR orders should be part of the physician and nursing discharge plan for all appropriate patients.

• Many states are working to make out-of-hospital DNR orders the standard for nursing homes and other community-based care facilities so that emergency medical services personnel responding to these facilities can honor DNR requests.

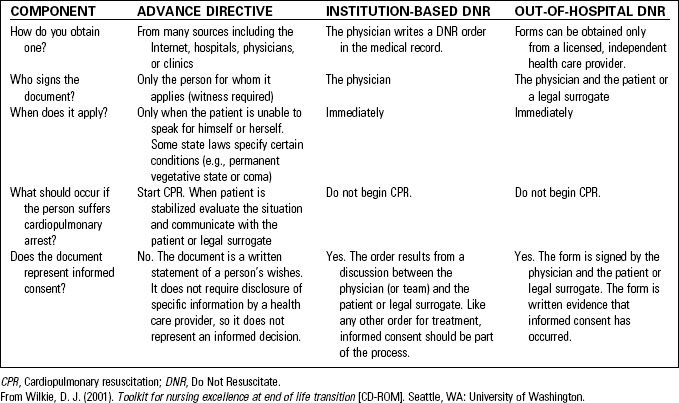

Importantly, an out-of-hospital DNR order is not an advance directive. The out-of-hospital DNR order is a physician’s order to withhold life-sustaining therapy, and it requires a patient’s or surrogate’s signature as evidence that informed consent occurred, similar to consent for a surgical procedure. Table 17-2 summarizes specific differences between advance directives, institution-based DNR orders, and out-of-hospital DNR orders.

Common Medical Emergencies at the End of Life

Uncontrolled Pain

Patients with chronic illness often present with moderate to severe pain related to their diagnosis and disease trajectory. Effective pain control is possible for the vast majority of patients at the end of life. (See Chapter 11, Care of the Patient with Pain, for more information.)

• If the patient is comatose or unable to verbalize pain status, closely monitor the patient’s vital signs and facial expressions, and note any guarding and increased restlessness. Clinicians should provide pain medication when indicated.

• The doses of analgesics and routes may be different from those used in routine practice. Patients at the end-of-life often receive drugs through transdermal patches, intrathecal infusions, or continuous IV drips at doses many times greater than those used for standard therapy. Careful assessment of patients with transdermal patches is necessary to maintain patient safety when additional pain medications are indicated.

Delirium

Delirium is defined as an acute change or fluctuation in mental status accompanied by inattention and the presence of disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness.6 Essential criteria for the diagnosis of delirium are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree