I

II

III

IV

V

Chamber (s) paced

Chamber (s) sensed

Response to sensing

Rate modulation

Multisite pacing

O → none

A → atrium

V → ventricle

D → dual (A + V)

O → none

A → atrium

V → ventricle

D → dual (A + V)

O → none

T → triggered

I → inhibited

D → dual (A + V)

O → none

R → rate modulation

O → none

A → atrium

V → ventricle

D → dual (A + V)

S → single (A or V)

S → single (A or V)

13.2.2 Unipolar Versus Bipolar Leads

Artifacts during electrocauterization can be erroneously considered by the CIED as spontaneous fast electrical activity of the heart (oversensing) [7]. Nearly all leads implanted in the last decade are bipolar, meaning that both the cathode and the anode are on the tip of the catheter, reducing the inter-electrode distance and the likelihood of external interferences. However, in some patients, especially with less recent implantations, unipolar leads can still be present. In these patients, the risk of oversensing is particularly high, as the sensed field is included between the tip of the lead (functioning as a cathode) and the generator (anode).

13.2.3 Unipolar Versus Bipolar Electrocautery

Electrosurgery current usually occurs in the frequency range between 100 and 5000 kHz and is typically delivered in a unipolar configuration between the cauterizing instrument and ground electrode. Bipolar electrosurgery involves the use of an electrical forceps where each limb is an electrode; it is used far less commonly because it is useful only for coagulation and not dissection. Bipolar systems deliver the current between two electrodes at the tip of the instrument, reducing the likelihood for EMI with CIEDs. Therefore, malfunctions are associated with unipolar electrocautery only, while bipolar electrosurgery does not cause EMI when not directly applied to CIED.

EMI usually occur when electrosurgery is performed within 8–15 cm from the device. Electrosurgery below the umbilicus with the grounding pad placed on the thigh is therefore unlikely to result in EMI with thoracic CIEDs.

EMI are more likely with the cutting mode rather than with the coagulation mode of surgical electrocautery, probably because of the higher power and the longer period of time applied for tissue cutting than coagulating a bleeding vessel.

The use of a harmonic scalpel, an ultrasonic cutting and coagulating instrument, can avoid surgical diathermy, according to some data [8].

13.2.4 Effects of EMI on CIED: General Considerations

Depending on the type of devices and lead, the programming of the devices and the type of surgery, different malfunctions can be found.

The possible effects of EMI can be transient (due to oversensing) or permanent (initiation of noise reversion, electrical reset mode, or increase of pacing thresholds).

Permanent damages are extremely rare, unless the energy is applied directly to the pulse generator or system electrode. There are some old reports of various serious effects, such as failure to pace, system malfunction, and even inappropriate life-threatening uncontrolled pacing activity [3]. However, because of the advances in lead and generator technology, most recent reports suggest that nowadays these effects infrequently occur.

13.2.4.1 Reset

Resetting of PMs has been reported in presence of energy coursing through the pulse generator (i.e., when the electrocautery touches, or is very close to, the generator) and simulates the initial connection of the power source at the time of manufacture. During reset, pacing parameters are automatically programmed in VVI mode with a lower rate from 60 to 70/min (depending on the manufacturer) and high output energy. For ICD, beside a VVI 60–70/min pacing mode, a fixed antitachycardia therapy (with lower rate cutoff ranging from 146 to 190/min according to the manufacturer) is programmed.

13.2.4.2 Generator Damages

The application of electrosurgery either in immediate close proximity or directly to the pulse generator can cause failure or permanent damage to a CIED, especially to older pacemakers (with voltage-controlled oscillators, no longer manufactured). ICDs may be more resistant, but energy can still enter the pulse generator in presence of breaches of lead insulation.

13.2.4.3 Lead-Tissue Interface Damage

Damage to the lead-myocardial interface is unlikely to occur with modern devices, but monopolar electrosurgery pathways crossing a pulse generator can produce enough voltage to create a unipolar current from the pulse generator case to a pacing electrode in contact with myocardium. This can result in a localized tissue damage with an increase in pacing threshold and possible loss of capture [9].

13.2.4.4 Oversensing

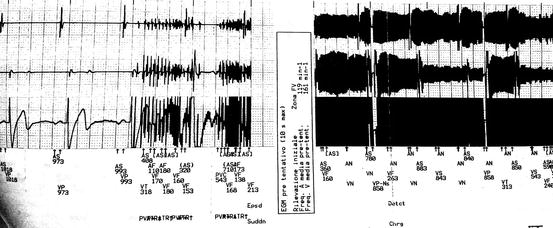

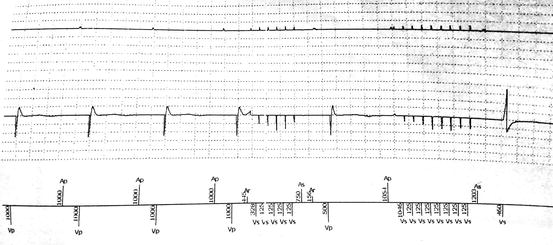

The most frequent CIED interaction with EMI is oversensing, leading inappropriate inhibition of pacing output and false detection of a tachyarrhythmia, with possible inappropriate CIED therapy (Fig. 13.1).

Fig. 13.1

Ventricular oversensing during thoracic surgery leading to ICD charge

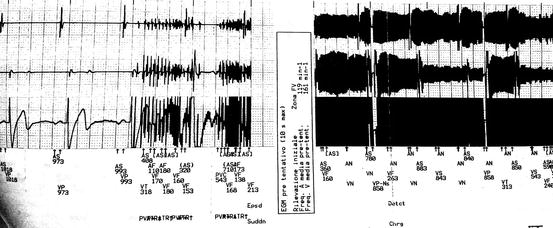

Electrosurgery applied below the umbilicus is much less likely to cause PM or ICD interference than when applied above the umbilicus. However, endoscopic gastrointestinal procedures that use electrosurgery may result in interference (Fig. 13.2). In a recent analysis on 71 subjects with ICD, EMI were recorded in 50 % of thoracic and head or neck procedures, 22 % of upper extremity procedures, 7 % of abdominal/pelvic procedures (laparoscopic cholecystectomies only), and 0 % of lower extremity procedures. No EMI in any lower abdominal procedures were recorded [10].

Fig. 13.2

EMI during polypectomy

13.2.4.5 Pacemaker Response to EMI

When programmed in inhibited pacing modes (AAI, VVI, or DDI), pacing inhibition can occur in presence of EMI, with consequent bradycardia or asystole in PM-dependent patients. When programmed in tracking mode (DDD), sensing of EMI in the atrial channel (more likely to occur, because of the higher sensitivity necessary to detect atrial signals) could result in increased rate of ventricular pacing or false atrial arrhythmia detection and consequent “mode-switch” to inhibited pacing modes (VDI, VVI, or DDI).

For a patient with spontaneous underlying rhythm, pacing inhibition does not have any consequences, while in PM-dependent patients, a prolonged (>4–5 s) pacing inhibition can result in significant hemodynamic compromise. Therefore, limiting electrosurgery usage to shorter bursts is desirable and may be a safer approach than either reprogramming the CIED or placement of a magnet over the pulse generator [3].

In patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), ventricular stimulation is, or should be, always present at surface ECG; however, these patients are not usually pacemaker dependent, so will not experience hemodynamic difficulties if biventricular pacing is transiently interrupted, with the exception of patients with advanced spontaneous AV block and those treated with AV node ablation (“ablate and pace”).

13.2.4.6 ICD Response to EMI

The ICDs require a certain duration (several seconds) of continuous high-rate sensing to satisfy arrhythmia detection criteria and consequently start the treatment (antitachycardia pacing or DC shock). Therefore, short bursts (<5 s) of electrosurgery alternating with pauses lasting some seconds are unlikely to result in false tachyarrhythmia detection and inappropriate antitachycardia therapies.

Inappropriate ICD shocks, although painful in nonsedated patients, should not be necessarily considered a serious danger for both the patient (apart from skeletal muscle contraction even if the patient is paralyzed by curare) and the people surrounding, who will not experience any shock. There is, however, a rare but possible proarrhythmic effect of DC shocks, which can initiate ventricular fibrillation.

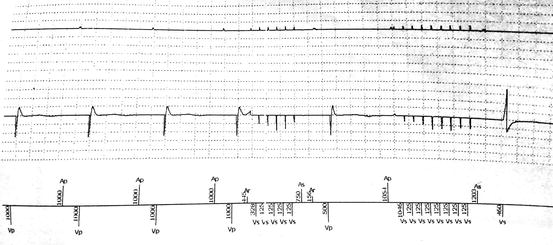

13.2.5 Effects of the Magnet

A simple magnet (typically 90 G) should always be present in the operating room when a patient with a CIED undergoes a procedure potentially causing EMI. However, the effect of the magnet positioned on the skin just above the device (Fig. 13.3) differs between pacemakers and ICDs.

Fig. 13.3

A magnet placed on the CIED pocket

13.2.5.1 Pacemakers

When a magnet is applied on a pacemaker, it usually causes “asynchronous pacing” (generally VOO or DOO), meaning that pacing at a fixed rate is provided, independently from any sensed activity, ensuring cardiac stimulation (or avoiding inappropriate triggered activity) even in the presence of persistent artifacts. The pacing rate in the presence of a magnet is CIED characteristic and varies according to the battery charge.

If spontaneous ventricular activity is adequate, asynchronous pacing (provided by the magnet or by CIED reprogramming) can be unnecessary or even inappropriate and potentially dangerous, as the magnet rate may compete with the patient’s rate; however, the risk that asynchronous pacing in patients with intrinsic rhythm can potentially induce atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, although widely feared, is very low [11].

13.2.5.2 Implantable Defibrillators

In ICDs, arrhythmias detection or tachycardia therapy can be disabled by magnet application and is automatically re-enabled when the magnetic field is removed. In some elderly Boston Scientific (former Guidant) ICDs, antitachycardia therapy may be permanently, and not transiently, deactivated by magnet application, necessitating reprogramming of the device or magnet repositioning to restore prior function. For this reason, and because it is possible to turn off magnet response in some devices, careful monitoring is required during the procedure to determine the effects of cauterization.

If inappropriate antitachycardia therapies (shock or antitachycardia pacing) should be delivered despite the magnet, shorter bursts (<5 s) with pauses between bursts, or bipolar cautery, are mandatory. On the other side, when true sustained ventricular arrhythmias occur, appropriate antitachycardia therapies can be delivered by the device by just removing the magnet or by using an external defibrillator. In this case, external pads should be placed in the anteroposterior rather than anterolateral position, ensuring the anterior (apical) pad is at least 5 cm away from the device.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree