16 Emergencies in Infants and Toddlers

• Use a systematic approach to evaluate and manage infants and toddlers. Know common milestones and age-specific manifestation of illness, take an “AMPLIFIEDD” history, do a “head-to-toe” physical examination, and use the “head-to-toe” memory tool to generate an expanded differential diagnosis.

• Do not make the diagnosis of infantile colic on first episode of excessive crying. Remember Wessel’s rule of 3.

• When the cause of illness in an infant or toddler is not obvious, the emergency practitioner should maintain a high level of suspicion for abuse, accidental toxin ingestion or exposure, intussusception, infection, and nonconvulsive seizure activity.

Perspective

More than 20% of emergency department (ED) visits are by pediatric patients, and a large proportion involve children 4 years or younger.1,2 Common reasons for ED visits in this age group include traumatic injuries, fever, respiratory complaints, and gastrointestinal problems.3–5 Although many of the disease processes are self-limited, it is imperative that the emergency practitioner (EP) identify infants and children at risk for progression to serious illness.

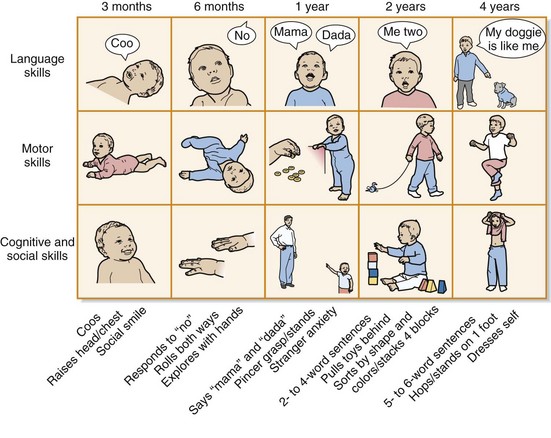

Knowledge of developmental milestones and age-specific manifestations of illness, in addition to taking a thorough history and physical examination, will greatly enhance the clinician’s ability to diagnose and initiate appropriate therapeutic interventions. From early infancy to the toddler stage, remarkable developmental changes occur. Understanding the changes in language, motor, cognitive, and social skills is important to properly assess infants and toddlers (Fig. 16.1). Many of the common illnesses experienced are age related (Table 16.1), and early recognition of the signs and symptoms of the specific diseases that threaten infants and toddlers is an effective strategy. Taking an “AMPLIFIEDD” history (Box 16.1) and performing a “head-to-toe” physical examination allow the clinician to gather the clinical clues needed to generate a comprehensive differential diagnosis. Practitioners in the ED are encouraged to develop an expanded differential diagnosis by using their knowledge of anatomy to aid memory (Table 16.2).

Table 16.1 Age-Related Differential Diagnosis for Various Chief Complaints (Overlap Can Occur)

| INFANTS | TODDLERS | |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Complaints | ||

| Cough | ||

| Wheezing | ||

| Gastrointestinal Complaints | ||

| Vomiting | ||

| Abdominal pain | ||

| Neurologic Complaints | ||

| Seizures | ||

Box 16.1 The “AMPLIFIEDD” History

Allergies: to medications, environmental allergens

Medications: prescription, over the counter, natural remedies

Past medical or surgical history:

Last “feed, pee, poop”: Feeding, stool, and urine pattern; use of formula (dilution?)

Immediate events (history of present illness and review of systems): OLD CAARS

Emergency medical service history: Elicit history of potential trauma, ingestion, abuse, or toxin exposure

Doctor: Name of primary care physician or specialist for additional information and help

Table 16.2 The “Head-to-Toe” Memory Tool

| “HEAD-TO-TOE” PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | POTENTIAL CLINICAL FINDINGS | GENERATE “HEAD-TO-TOE” DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS (EXAMPLES) |

|---|---|---|

| Head | Bulging fontanelle Step-off, laceration, ecchymosis, hematoma Ventriculoperitoneal shunt | |

| Eyes | Icterus, conjunctival injection, cranial nerve deficit, retinal hemorrhage | |

| Nose | Congestion | |

| Mouth | Poor dentition | |

| Neck | Mass | |

| Chest Pulmonary Cardiac | Chest wall tenderness Stridor, rales, rhonchi, wheezing, murmur, dysrhythmia | |

| Abdomen Gastrointestinal tract Liver Pancreas Kidney and urinary tract Adrenal glands | Distention, tenderness, peritoneal signs, palpable mass | |

| Extremities | Deformity, tenderness, edema, induration, erythema | |

| Skin | Rash, petechiae | |

| Neurologic | Weakness, decreased reflexes |

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Infant or Toddler in the Emergency Department

The Crying Infant

Perspective

One of the most challenging aspects of pediatric emergency care is managing an infant with the nonspecific symptom of acute, excessive crying. Infants are not able to vocalize complaints, and crying is the primary mode of communication until language development. According to Brazelton, most babies will cry between  and 3 hours per day in the first 3 months of life, with the peak occurring at approximately 6 weeks.7 By the time that parents bring their crying infant or toddler to the ED, they are often exhausted from attempts to console the child. In such circumstances, the EP must be able to distinguish between relatively benign conditions, such as colic, and severe, life-threatening illnesses, such as meningitis. An orderly approach to infants with excessive unexplained crying will allow the EP to diagnose the occasional severe illness and provide guidance to the caregivers.

and 3 hours per day in the first 3 months of life, with the peak occurring at approximately 6 weeks.7 By the time that parents bring their crying infant or toddler to the ED, they are often exhausted from attempts to console the child. In such circumstances, the EP must be able to distinguish between relatively benign conditions, such as colic, and severe, life-threatening illnesses, such as meningitis. An orderly approach to infants with excessive unexplained crying will allow the EP to diagnose the occasional severe illness and provide guidance to the caregivers.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of early excessive crying (e.g., >3 hours) in infants younger than 3 months has been estimated at 8% to 29%, but it may persist for months longer in up to 40% of these children.8 However, there is no accurate estimate of the incidence of excessive crying secondary to illness because almost every disease process can be accompanied by the symptom of crying. As infants grow and expand their repertoire for expressing specific needs, excessive crying is less frequently voiced as a primary complaint by caregivers.

Pathophysiology

During the first few months of life, infants are expected to have variable periods of prolonged crying, which is normal behavior. However, crying is considered excessive when parents complain about it. Most paroxysmal episodes of crying have a behavioral etiology. In 1954 Wessel published his “rule of 3” for diagnosing colic: when an otherwise healthy infant between the ages of 3 weeks and 3 months cries more than 3 hours per day for more than 3 days per week.9 However, if organic pathology is to be identified, the EP must recognize that excessive crying has meaning and may be indicative of acute illness. In a study of 56 infants with an episode of excessive, prolonged crying without fever or cause identified by the parents, 61% had a serious final diagnosis.10

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

After the primary survey is complete and it is determined that no emergency intervention is indicated, the EP needs to elicit a comprehensive AMPLIFIEDD history (Box 16.2) from the primary caregiver. Clinical findings on the head-to-toe evaluation suggesting a potential cause of the excessive crying may include the following:

• Signs of head trauma, such as scalp contusions, ecchymoses and lacerations, hemotympanum, postauricular hematomas, or periorbital ecchymoses

• A bulging fontanelle indicative of increased intracranial pressure

• A sunken anterior fontanelle consistent with dehydration

• Fluorescein uptake indicating corneal abrasions

• Retinal hemorrhages raising concern for serious abuse

• An erythematous and bulging tympanic membrane signifying otitis media

• Obstruction of the nares secondary to a foreign body

• Oral thrush or mucosal ulcers in the oropharynx often seen with stomatitis

• Exudative pharyngitis and fullness of the posterior pharynx suggesting peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscesses

• Wheezing, rales, or rhonchi indicating a respiratory infection

• Palpation of a mass during the abdominal examination, which can be associated with pyloric stenosis, intussusception, or a tumor

• Diaper rash, anal fissure, or impacted stool on rectal examination

• Scrotal swelling consistent with an incarcerated hernia or testicular torsion

• Extremity tenderness, edema, or bruising concerning for a possible fracture

• Erythema, induration, and tenderness suggesting a soft tissue infection (cellulitis or abscess)

• Hair tourniquet on a toe or finger

• Rashes with potentially life-threatening causes (e.g., petechiae, purpura)

Box 16.2 The AMPLIFIEDD History for a Crying Infant or Toddler

Medication (by mom or infant): Prescription, over the counter, natural remedies

Immediate events (history of present illness and review of systems): OLD CAARS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree