Fig. 15.1

Partial task training simulator developed to allow students to practice spinal and epidural anesthetic techniques. Device with puncture block removed (a) and ready for use (b)

Features that increase the effectiveness of partial task training devices for education are those that allow the learner to translate what he/she has learned in the simulation lab into the clinical setting [11]. Lifelike anatomical features coupled with realistic tissue resistance allow the student to experience these procedures more realistically. In earlier devices, puncture sites remained visible on the “skin” so that subsequent students knew where to place the needle. Modern devices include skin that can quickly and easily be removed using magnetic clips or Velcro and contain removable transparent puncture blocks that allow the student to view the vertebrae, puncture sites, and the associated needle tract. Because it is often difficult for the student to conceptualize the various anatomic parts of the axial skeleton, having a model available for reference can be helpful for demonstration purposes (Fig. 15.2).When demonstrating proper needle placement, the use of full skeletal adjuncts (Fig. 15.3a) can make visualization easier. Needle placement for midline lumbar (Fig. 15.3b), paramedian lumbar (Fig. 15.3c), and thoracic epidural (Fig. 15.3d) placement can be easier to conceptualize when first demonstrated on such a device. During proper patient position management and skin preparation techniques, students should be encouraged to “gown and glove” just as they would during the care of an actual patient in order to emphasize the need for following strict aseptic technique. One demonstration that is helpful involves the use of color sensitive dye placed on the “sterile” gloves of the student so that, post-procedure, it is obvious which areas of the field and surrounding area have actually been touched.

Fig. 15.2

Cross-sectional anatomic model of the spinal canal and associated structures

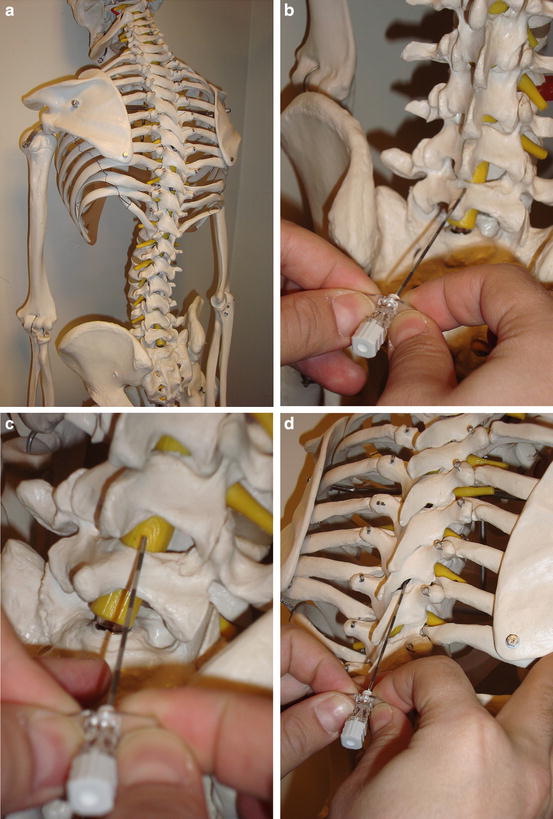

Fig. 15.3

Skeletal model showing natural curvature of the lumbar and thoracic spine (a) can be used to demonstrate proper needle placement for anesthesia requiring a midline lumbar (b), paramedian lumbar (c), or thoracic (d) approach

Scenarios Specific to Urologic Surgery for Full-Environment Simulation

The current use of today’s patient simulators reflects the time and resources available to the instructor. Some educational sessions may be as simple as a “run through” of a case with no intraoperative complications in which students are evaluated on their performance using a checklist of things that should be done, while others involve the entire simulation theater [12]. In the full simulation environment, which is true theater, an extreme level of detail is used to create emotion, confusion, and distraction and add that element of reality that helps to solidify the lesson [13]. Instead of simply completing the tasks on an anesthesia checklist, participants interact with a number of actors, many of whom may be difficult or inappropriate, verbally abusive, or unhelpful. The following scenarios illustrate some classic perioperative complications in urology.

Patient Develops Shortness of Breath After Placement of Regional Anesthesia

The choice of anesthetic in urologic surgery is often a regional technique, driven by the desire to provide adequate analgesia, increase patient safety, reduce unwanted sequelae of general anesthesia, and avoid potentially nephrotoxic drugs. While any of the urologic procedures can be performed under general anesthesia, and with the understanding that general anesthesia is always the backup plan should a regional technique fail, regional anesthesia with or without sedation has certain advantages. In this scenario, a technique commonly performed under spinal anesthesia, such as a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), in an otherwise healthy patient is presented to the student who must develop the anesthetic plan. Should the student prefer a general anesthetic, the “surgeon” can argue against this plan to persuade him/her towards a regional technique. In addition to providing an opportunity for a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of this technique, a partial task- training device such as the one described above can be used to allow the student to practice the administration of spinal anesthesia. It is important to have the students describe what they are doing as they look for landmarks and place the needle in the ‘patient’s’ back so that any corrections to base knowledge can be made in real time. It is also an opportunity to cover different techniques such as the paramedian approach.

An intensive discussion of proper spinal technique serves two purposes. First, it ensures that the student has a firm grasp of all aspects of the procedure and is able to anticipate the next step without assistance from the instructor. Allowing the student to perform a spinal anesthetic on the partial task training device while observing sterile technique can graphically illustrate the need for prior proper planning when, with the needle placed firmly in the patient’s back, the student realizes that he/she has to break scrub in order to obtain required but missing or unopened equipment. Secondly, and this is less obvious but important for the scenario, the discussion serves as a distraction from the impending complication.

Presumably all goes well, and the patient begins to report the expected feelings of numbness and paresthesias. Placed in the lithotomy position with the drapes up, the surgeon starts the surgery, while the student attends to the patient and the various monitors. When the patient begins to complain of shortness of breath, any number of problems could be developing, and the student should vocalize the differential as he/she attempts to intervene. Is the patient hypotensive because of the spinal level? Is it an anxiety attack? Is the patient actually weak from a spinal level that is too high? The student should be given the opportunity to identify and treat the actual cause in real time as the scenario unfolds, providing respiratory and cardiovascular support as needed. Alternative beginnings to this scenario for the more advanced student include the failed spinal (should the block be repeated or should general anesthesia be an immediate choice?) or failed epidural (should the epidural catheter be replaced, a spinal anesthetic performed, or general anesthesia instituted?). Once the patient is stable, a discussion of the etiology of this phenomenon as well as the appropriateness of the student’s treatment plan can occur. Debriefing should include a discussion of the relevant physiology and pharmacology as well as the “unicorns” such as neurally mediated syncope that most students might not get a chance to manage during training [14].

Patient Is Confused and Complaining of Chest Pain in the Postanesthesia Care Unit After a Transurethral Resection of the Prostate

Because of the large volume of irrigation used to clear the surgical field in this operation, significant absorption may occur. Due to the need for an irrigant with a low index of refraction and because electrical conduction is a problem with balanced salt solutions, the isoosmotic fluids, mannitol, glycine, or sorbitol are typically used. Absorption of large amounts of these fluids can lead to significant problems related to electrolyte imbalance. Hyponatremia can cause nausea and vomiting, hypertension, mental status changes including seizures when the sodium drops below 120 meq/l, and dysrhythmias or cardiovascular collapse when the level falls below 100 meq/l. These changes can precipitate myocardial infarction in the patient at risk, but in this setting, the possibility of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) syndrome complicates the matter. In this scenario, the student must assess the patient and quickly gather the information necessary to correctly diagnose the problem and then provide appropriate treatment in real time as the patient’s condition begins to deteriorate.

For this scenario, the student is covering the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and is called to evaluate the patient who is just about to be discharged. The nurse has removed all of the monitors and taken out the intravenous line when the patient begins to complain of chest pain. This situation brings up multiple issues, and the scenario can be tailored to the skill level of the student. Provided there are no contraindications to regional anesthesia, such as a coagulopathy or severe valvular disease, these cases are usually done under spinal anesthesia so that the patients’ mental status can be monitored for mental status changes that would suggest the development of TURP syndrome. Here in the PACU, this patient has recovered from regional anesthesia, but without examining the chart, the student does not know this. Is it possible this case was done under general anesthesia? If so, then why? Does this patient have some greater risk for postoperative hemorrhage? What other clues might be found in the patient’s record? If the instructor wishes to steer the student towards any specific diagnosis, suggestions regarding management or laboratory investigations can be made by support staff such as the PACU nurse or surgical team member. Table 15.1 lists the current recommendations for the evaluation and treatment of the patient with acute coronary syndrome. The same scenario can just as easily be altered to that of a pure post-procedure cardiac arrest, and at the very basic level provides a reasonable background to introduce advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocol as the patient may present with a number of different dysrhythmias [15].

Table 15.1

AHA guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of the acute coronary syndrome

Correct root cause of ischemia (consider hypoxia, hypotension, hypercarbia, electrolyte imbalances, dysrhythmias) |

Remember MONA(H) B |

Morphine |

Oxygen |

Nitrates |

ASA |

Heparin |

Beta blockers |

Intraoperative Hypotension During Cystectomy

There are three basic types of cystectomy: simple, partial, and radical, and each is performed with a midline, transperitoneal incision in the supine position. Even a simple cystectomy can be associated with significant blood loss, though this is much more common in the radical cystectomy, so a discussion regarding the availability of blood and blood products is appropriate. For the neophyte who is comfortable with concepts but who has not yet experienced the realities of clinical practice, this is the perfect moment to discuss factors that might delay obtaining blood for transfusion and emphasizing the importance of planning ahead. If this is not an elective case and blood is not available, consider waiting until it is!

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree