INTRODUCTION

OTITIS MEDIA

Children between the ages of 6 months and 2 years are at highest risk of developing acute otitis media (AOM). Children at increased risk of recurrent AOM contract their first episode prior to 12 months, have a sibling with a history of recurrent AOM, are in day care, or have parents who smoke.

AOM is an acute inflammation and effusion of the middle ear. Viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens may cause AOM. The pathogenesis of bacterial AOM is eustachian tube dysfunction, typically following a viral infection, allowing retention of secretions (serous otitis) and seeding of bacteria. The most common bacterial isolates are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pyogenes. There is an increased prevalence of antimicrobial resistance for S pneumoniae and β-lactamase-producing strains of H influenzae. Vaccination for strains of S pneumoniae has resulted in a modest decrease in incidence of AOM.

Patient presentations and complaints vary with age. Infants with AOM have vague, nonspecific symptoms (irritability, lethargy, and decreased oral intake). Young children can be irritable, often febrile, and frequently pull at their ears, but they may also be completely asymptomatic. Older children and adults note ear pain, impaired hearing, and occasionally otorrhea.

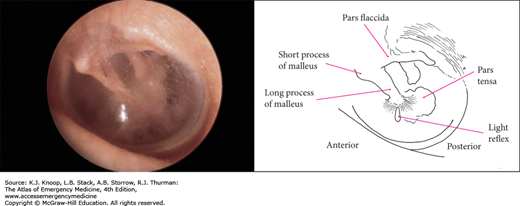

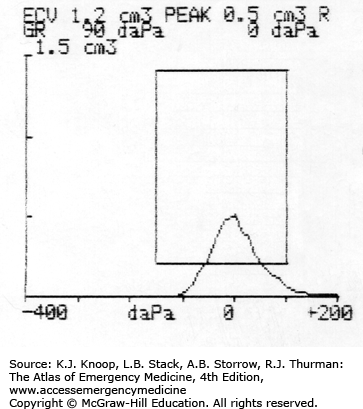

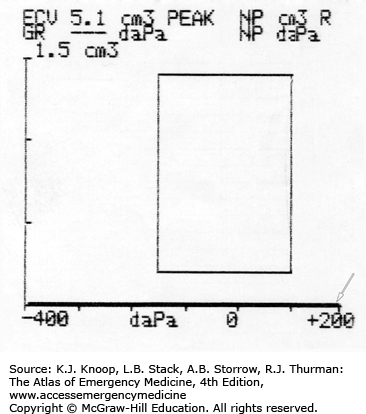

Otoscopy should focus on color, position, translucency, and mobility of the tympanic membrane (TM). Compared with the TM of a normal ear, AOM causes the TM to appear dull, erythematous or injected, bulging, and less mobile. The light reflex, normal TM landmarks, and malleus become obscured. Pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry enhance accuracy in diagnosing AOM.

Although AOM generally resolves spontaneously, most patients are treated with antibiotics and analgesics. Steroids, decongestants, and antihistamines do not alter the course in AOM but may improve upper respiratory tract symptoms.

Follow-up in 10 to 14 days or return if symptoms persist or worsen after 48 hours is appropriate and patients should be referred to an otolaryngologist for further evaluation, an audiogram, and possible tympanostomy tubes if they have significant hearing loss, failure of two complete courses of outpatient antibiotics during a single event, chronic otitis media (OM) with or without acute exacerbations, or failure of prophylactic antibiotics.

AOM is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of distinct fullness or bulging of the TM.

In children, recurrent OM may be due to food allergies.

Only 4% of children less than 2 years with AOM develop temperatures greater than 104°F. Those with fever higher than 104°F or with signs of systemic toxicity should be closely evaluated for other causes before attributing the fever to AOM.

Most children over 2 years qualify for observation for 48 hours prior to initiation of antibiotics.

Management of AOM may require narcotic analgesia; topical Auralgan may decrease pain.

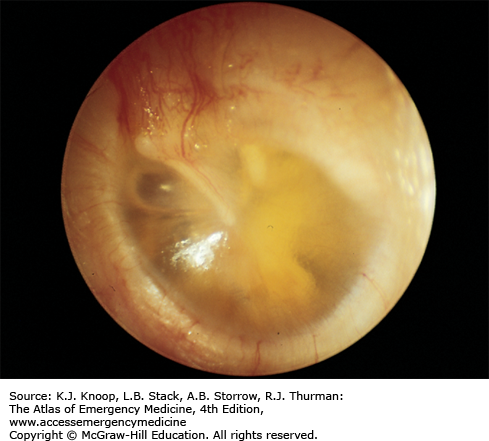

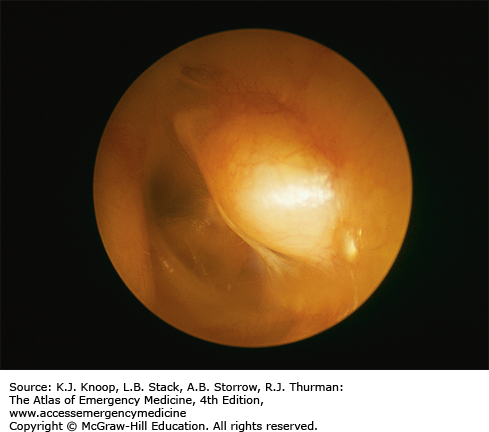

FIGURE 5.6

Serous Otitis Media with Effusion (OME). Serous OME is commonly seen after AOM, but it is also common without this history. Any process that leads to obstruction of a eustachian tube may cause OME. A clear, amber-colored effusion with a single air-fluid level is seen in the middle ear behind a normal tympanic membrane. (Photo contributor: C. Bruce MacDonald, MD.)

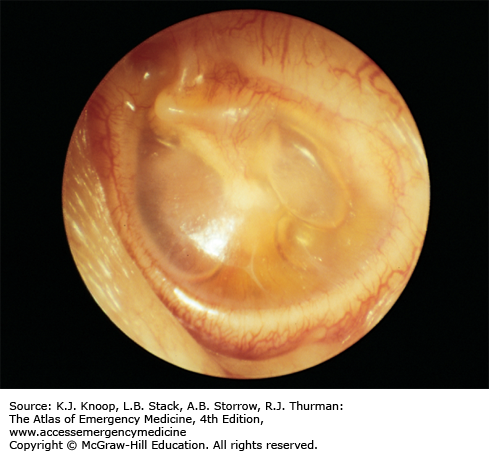

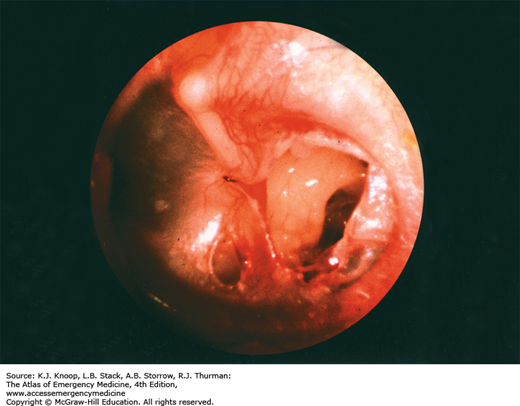

BULLOUS MYRINGITIS

Bullous myringitis is a direct inflammation and infection of the TM secondary to a viral or bacterial agent. Vesicles or bullae filled with blood or serosanguinous fluid on an erythematous TM are the hallmarks. Frequently, a concomitant OM with effusion is noted. Typical pathogens are the same as seen in AOM.

The onset of bullous myringitis is preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection and is heralded by sudden onset of severe ear pain, scant serosanguinous drainage from the ear canal, and frequently some degree of hearing loss. Otoscopy reveals bullae on either the inner or outer surface of the TM. Patients presenting with fever, hearing loss, and purulent drainage are more likely to have concomitant infections, such as OM and otitis externa (OE).

Differentiation between viral and bacterial etiologies for TM bullae is not necessary. Although most episodes resolve spontaneously, many physicians prescribe antibiotics. Warm compresses, topical or strong analgesics, and oral decongestants provide symptomatic relief. Referral is not necessary in most cases unless rupture of the bullae is required for pain relief.

Instruct parents that TM rupture may occur with sudden resolution of the pain and drainage from the ear canal.

Carefully differentiate TM bullae from cholesteatomas or herpetic vesicles.

Facial nerve paralysis associated with clear, fluid-filled TM vesicles is characteristic of herpes zoster oticus (HZO).

CHOLESTEATOMA

Cholesteatomas are collections of desquamating stratified squamous epithelium found in the middle ear or mastoid air cells. Congenital cholesteatomas occur most frequently in children and young adults. Acquired cholesteatomas originate from perforation or retraction of the TM allowing migration of epithelium into the middle ear.

Injury may occur to middle ear ossicles through the production of collagenases, and may erode into the temporal bone, inner ear structures, mastoid sinus, or posterior fossa dura. Treatment delays can lead to permanent conductive hearing loss or infectious complications.

Many cholesteatomas have an insidious progression without associated pain or symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) scans may reveal bony destruction.

Refer initial diagnosis. No medical or surgical management is required unless they become symptomatic.

Persistent pain associated with headache, facial motor weakness, nystagmus, or vertigo suggests inner ear or intracranial involvement.

Polyps found on the TM can indicate the presence of a cholesteatoma and require further evaluation to exclude its presence.

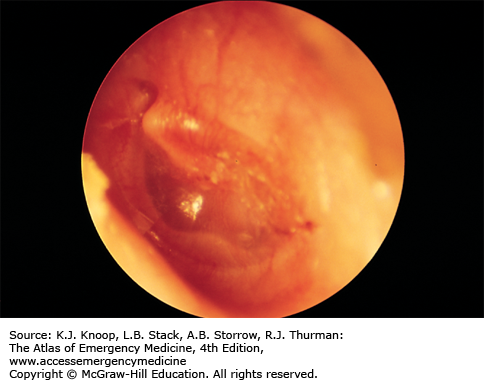

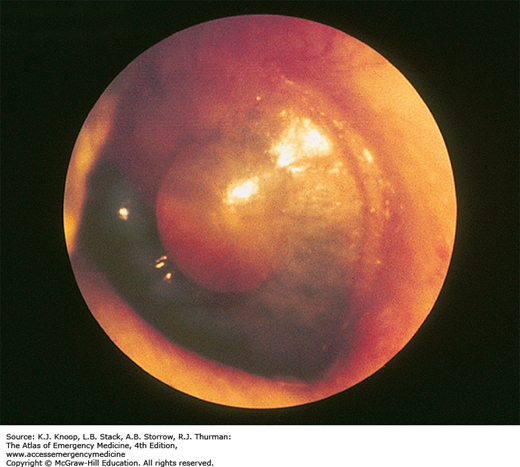

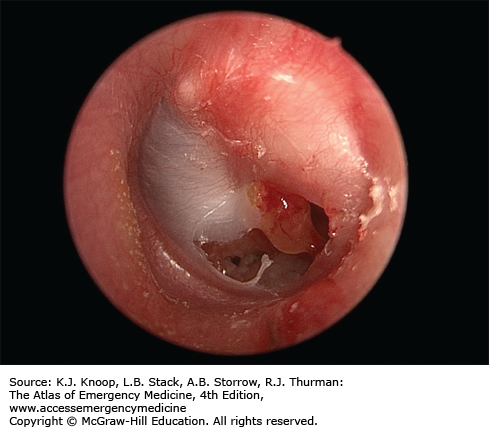

FIGURE 5.12

Acquired Cholesteatoma. This is a left ear with an inferior perforation and granulation tissue present just below the tip of the malleus. A white mass is seen behind the eardrum in the posterosuperior quadrant, roughly 12-o’clock to 3-o’clock position. This patient had a history of PE tubes placed several years ago with a resultant perforation allowing squamous epithelium access to the middle ear. (Photo contributor: David R. White, MD)

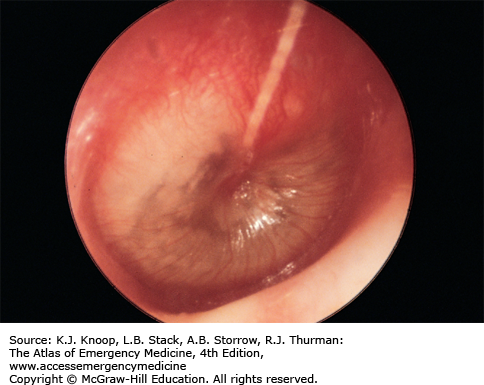

TYMPANIC MEMBRANE PERFORATION

Acute tympanic membrane (TM) perforations are caused by direct penetrating trauma, barotrauma, OM, corrosives, thermal injuries, and iatrogenic causes (foreign-body removal, tympanostomy tubes). TM perforations are occasionally accompanied by injuries to the ossicular chain and temporal bone.

Patients with an acute TM perforation complain of a sudden onset of ear pain, vertigo, tinnitus, and altered hearing after a specific event. Physical examination of the TM reveals a slit-shaped tear or a larger perforation with an irregular border, often associated with blood along the margins. Subacute or chronic perforations have smooth margins and a round or ovoid shape.

Treatment of acute TM perforations is tailored to the mechanism of injury. All easily removable foreign bodies should be extracted. Corrosive exposures require face, eye, and ear decontamination. Antibiotics and irrigation do not improve the rate or completeness of healing unless the injury is associated with OM. Systemic antibiotics should be reserved for perforations associated with OM, penetrating injury, and possibly water-sport injuries (see “Otitis Media” above). Topical steroids impede perforation healing.

Patients are instructed to avoid water in the ear while the perforation is healing and to return if symptoms of infection appear. While nearly 80% of all TM perforations heal spontaneously, all TM perforations require referral to an otolaryngologist for follow-up for possible myringoplasty.

Corticosteroid eardrops of any formulation retard spontaneous healing and should be avoided.

Traumatic TM perforation associated with cranial nerve (CN) deficits or persistent vertigo requires immediate otolaryngology consultation due to possible temporal bone fractures or injury to the round or oval window.

OTITIS EXTERNA

Otitis externa (OE), or “swimmer’s ear,” is an inflammation and infection (bacterial or fungal) of the auricle and external auditory canal (EAC). Typical symptoms include otalgia, pruritus, otorrhea, and hearing loss. Physical examination reveals EAC hyperemia and edema, otorrhea, occlusion from debris and swelling, pain with manipulation of the tragus, and periauricular lymphadenopathy.

Several factors predispose the EAC to infection: increased humidity and heat, repeated water immersion, foreign bodies, trauma, hearing aids, and cerumen impaction. Bacterial OE is primarily an infection due to Pseudomonas species or Staphylococcus aureus. Diabetics are particularly prone to infections by Pseudomonas, Candida albicans, and, less commonly, Aspergillus niger.

EAC irrigation and suctioning is recommended to thoroughly evaluate the EAC. Topical antibiotic suspensions containing polymyxin, neomycin, and hydrocortisone or ciprofloxacin with ear wicks are effective. Topical solutions are not pH-balanced and thus are irritating and may cause inflammation in the middle ear if a perforation is present. Topical fluoroquinolones may be less irritating and are only given twice a day. Systemic antibiotics are not indicated unless extension into the periauricular tissues is noted. Patients should avoid swimming and prevent water from entering the ear while bathing. Dry heat aids in resolution, and analgesics provide symptomatic relief. Follow-up should be arranged in 10 days for routine cases.

Resistant cases may have an allergic or eczematous component. These typically present with a dry, scaly, itchy EAC and are chronic in nature.

Drying the EAC after water exposure with a 50:50 mixture of isopropyl alcohol and water or with acetic acid (white vinegar) minimizes recurrence. If the TM is possibly perforated, isopropyl alcohol should be avoided.

If a TM perforation is suspected and antibiotic drops are indicated, a suspension is recommended.

Consider malignant OE, typically caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in elderly, diabetics, or immunocompromised patients. Exposed bone, ulceration of the EAC, and facial nerve weakness are hallmarks.

PREAURICULAR SINUS ABSCESS

Preauricular sinus abscesses arise from pits or fissures originating from congenital malformations of the preauricular soft tissues. They are located near the front of the ear and mark the entrance to a sinus tract. These are lined with squamous epithelium and thus may produce epithelial-lined subcutaneous cysts, which may become infected, leading to cellulitis or abscess. Patients may have other congenital anomalies such as hearing loss or renal disease. Patients may present with recurrent ear discharge, pain, swelling, redness, itching, headache, and fever. The diagnosis is often overlooked in early stages.

Initiate oral antibiotics to cover for S aureus (most common). Incision and drainage should be avoided in the emergency department (ED). Needle aspiration may be attempted and may give some relief. Arrange follow-up with an otolaryngologist for complete excision of the sinus track.

Preauricular sinus abscesses may be confused with first branchial cleft cysts.

Because of their close proximity to the facial nerve, referral to a specialist who is familiar with the underlying anatomy is recommended.

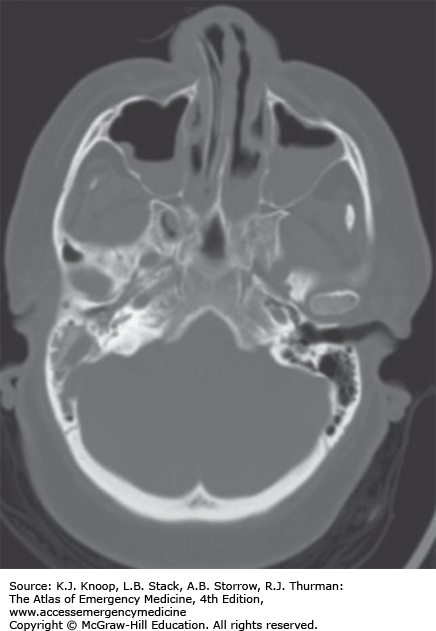

MASTOIDITIS

Mastoiditis is an infection or inflammation of the mastoid air cells often resulting from extension of purulent OM with progressive destruction and coalescence of air cells. Medial sinus wall erosion can cause cavernous sinus thrombosis, facial nerve palsy, meningitis, brain abscess, and sepsis. With the use of antibiotics for AOM, the incidence of mastoiditis has fallen sharply.

Patients present with fever, chills, postauricular ear pain, and otorrhea. Patients may have tenderness, erythema, swelling, and fluctuance over the mastoid process; proptosis of the pinna; erythema of the posterior-superior EAC wall; and otorrhea.

Initial evaluation includes a thorough head, neck, and CN examination. Contrasted CT of the head or mastoid sinus may reveal bone erosion and intracranial involvement.

While oral penicillinase-resistant penicillins, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, third-generation cephalosporins, and the newer macrolides are effective in mild cases of mastoiditis, severe cases require parenteral antibiotics. Mastoiditis requires prompt consultation and close follow-up.

Most patients require admission for parenteral antibiotics to cover H influenzae, M catarrhalis, streptococcal species, and S aureus.

Surgical incision and debridement, and possibly mastoidectomy, are reserved for refractory cases.

Chronic mastoiditis describes chronic otorrhea of at least 2-month duration. It is often associated with craniofacial anomalies.

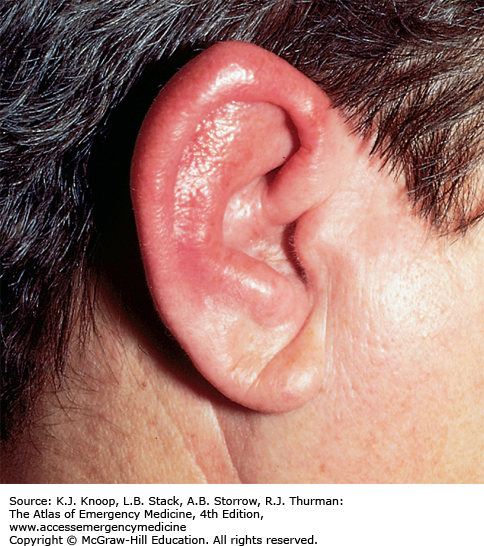

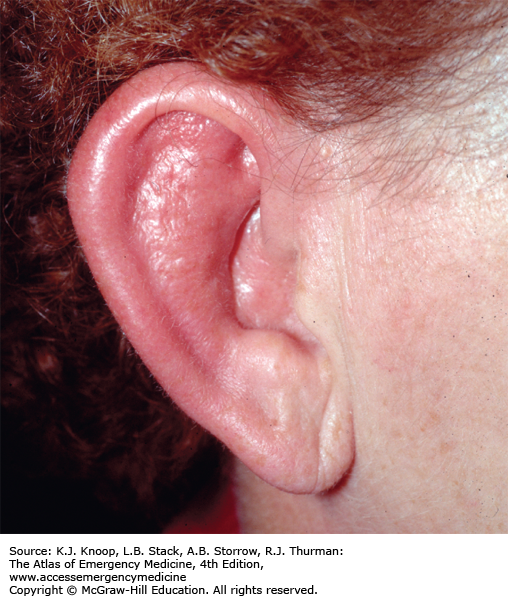

AURICULAR PERICHONDRITIS

Auricular perichondritis is a bacterial infection of the overlying skin and perichondrium of the ear, by definition sparing the auricular cartilage. Causative organisms include P aeruginosa, S aureus, and S pyogenes. Predisposing factors for auricular perichondritis include surgery, ear piercing, burns, frostbite, insect bites, and contact sports. Auricular perichondritis may be an extension of OE. Clinical findings include a swollen, tender, erythematous, and warm auricle, which may involve the ear lobule, and often a fever; the TM is unaffected. Infectious perichondritis may be confused with relapsing polychondritis, an autoimmune condition involving the cartilage of the ears, nose, and trachea.

Outpatient management of the healthy patient includes appropriate oral antibiotics and follow-up in 48 hours. Hospitalization for parenteral antibiotics in the immunocompromised or diabetic patient is advised. Topical antibiotic otic drops should be used if the external canal is involved. Relapsing polychondritis is treated as an outpatient with prednisone if involvement is confined to the ear.

P aeruginosa is the most common bacteria causing auricular perichondritis.

Ear piercing is the most common activity resulting in auricular perichondritis.

Findings of fluctuance and auricular deformity suggest auricular chondritis, a complication of perichondritis.