Ear Infections in Adults

Michael Cole and Sukhjit S. Takhar

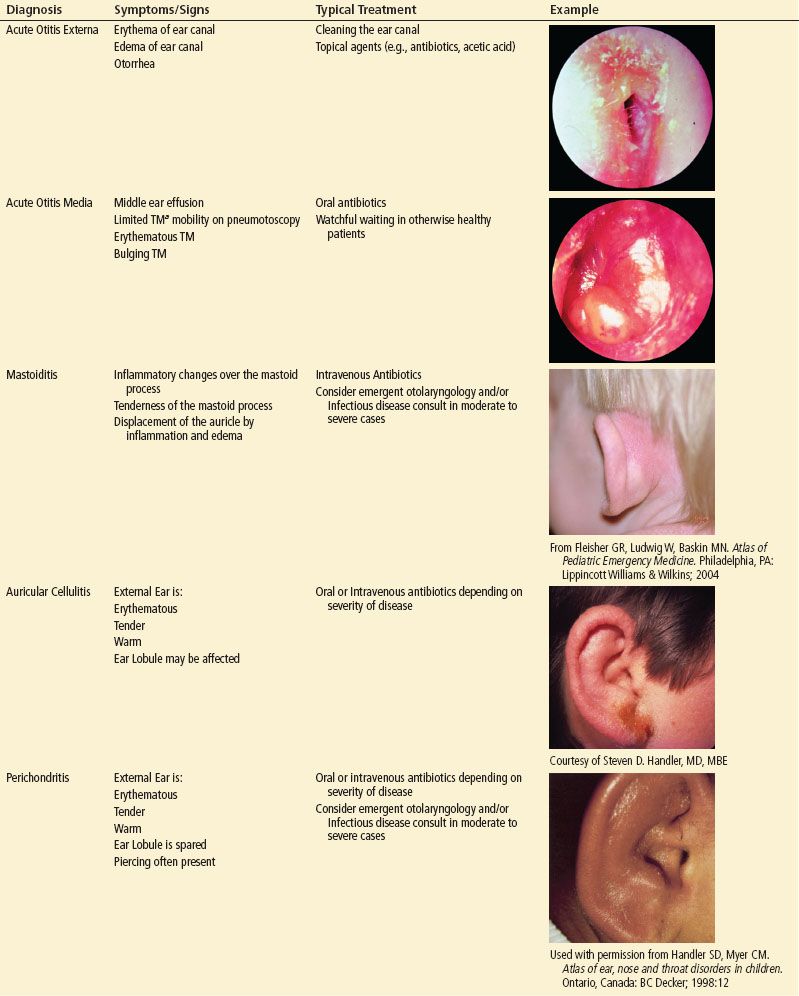

The vast majority of ear infections in the antibiotic era are benign and self-limited. However, there are certain life-threatening conditions that require prompt diagnosis and treatment (eTable 68.1).

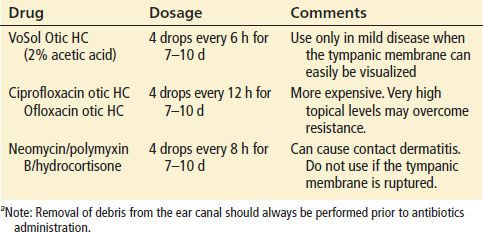

TABLE 68.1

Therapeutic Options for the Management of Otitis Externaa

eTABLE 68.1

Most Common Etiologies of Ear Pain

ACUTE OTITIS EXTERNA

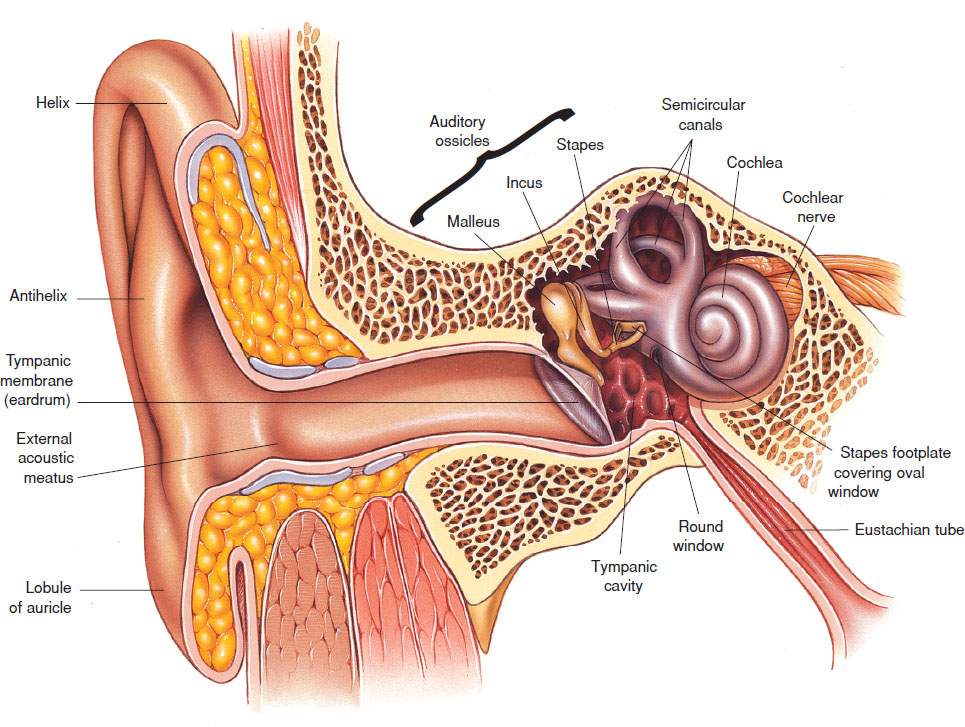

Acute otitis externa (AOE) is a diffuse inflammatory condition of the external ear canal. Knowledge of the anatomy helps to understand AOE and its complications. The external ear is composed of the external auditory canal (EAC) and the auricle. The outer portion of the external canal is cartilaginous with a well-developed dermal layer. The inner, or osseous, portion is lined by a thin layer of epithelium that is firmly attached to the periosteum of the temporal bone (Fig. 68.1). The narrowest part of the canal is the osseous–cartilaginous junction. Cerumen is produced by the apocrine glands and is required for a healthy ear canal. It is a thin, acidic, protective coat that is inhospitable to many microorganisms including those most commonly implicated in AOE (1).

FIGURE 68.1 Anatomy of the middle ear. Asset provided by Anatomical Chart Co.

The overlying squamous epithelium of the inner portion can be disrupted by direct trauma, prolonged use of ear plugs, ear phones or hearing aids, or maceration from prolonged water exposure, providing the initial insult that leads to infection (2). A warm, humid environment promotes bacterial growth. AOE, often known as swimmer’s ear, occurs most often in the summer months and in tropical climates with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus being the most common pathogens (3,4). Fungal infections are typically seen in chronic disease and occasionally cause AOE.

Invasive otitis externa, also called necrotizing otitis externa or malignant otitis externa, is a rare complication of otitis externa. Essentially it is osteomyelitis of the temporal bone, occurring when the infection spreads from the auditory canal to the temporal bone and nearby structures, like the cranial nerves. It was originally called malignant otitis due to the high associated mortality. It occurs most often in the elderly diabetic patient and occasionally in other immunocompromised patients. P. aeruginosa is the responsible organism in up to 98% of cases (5,6).

ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

Acute otitis media (AOM) is an inflammatory process of the middle ear. It occurs most commonly in young children. In adults, the pathophysiology and treatment are quite similar, with a few noteworthy differences.

Eustachian tube dysfunction is critical in the pathogenesis of otitis media. The tube connects the middle ear cavity to the nasopharynx and provides ventilation and drainage (see Fig. 68.1). Eustachian tube dysfunction may result from an upper respiratory tract infection, allergy, barotrauma, or nasopharyngeal tumor. These inciting factors may lead to congestion and accumulation of fluid behind the tympanic membrane (TM). If this fluid subsequently becomes infected by nasopharyngeal organisms, AOM is the result.

The most common organisms involved in AOM are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis (7,8). Viruses are often present as coinfection agents. Patients with chronic disease can be infected with Pseudomonas or S. aureus.

Complications of otitis media occur when the infection spreads beyond the confines of the middle ear. Intracranial spread may lead to meningitis, brain abscess, or lateral sinus thrombosis, whereas extracranial spread leads to TM perforation, mastoiditis, subperiosteal abscess, facial nerve paralysis, or petrous apicitis (9,10). Complications have decreased dramatically in the antimicrobial era.

It is noteworthy that the mastoid air cells are connected to the middle ear. In uncomplicated otitis media, patients often have fluid in the mastoid air cells. Therefore the finding of fluid in the mastoid air cells on imaging is nonspecific and requires clinical correlation. Mastoiditis is clinically diagnosed when there is tenderness over the mastoid prominence, displacement of the auricle posteriorly and inferiorly, and signs of inflammation.

AURICULAR CELLULITIS AND PERICHONDRITIS

Infections of the external ear structures are usually the result of local trauma or extension from a severe case of otitis externa. Auricular cellulitis is an infection of the dermis overlying the external ear and it is most often caused by streptococci or staphylococci.

Perichondritis is infection or inflammation of the perichondrium of the auricular cartilage. Piercing the upper third of the pinna (“high piercing”) has become fashionable, and it allows the introduction of bacteria into a poorly vascularized area. Although most infections are due to staph and strep, patients with recent (<1 month) piercings appear to have an increased incidence of pseudomonal infection (11,12). Cosmetic deformity following perichondritis is common and difficult to avoid.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The initial symptoms of otitis externa may be pruritus and a sensation of fullness, which can progress to more severe pain, mucopurulent discharge, and hearing loss (13). Infection may spread beyond the ear canal, leading to pain in surrounding soft tissues and lymph nodes. Potential spaces, tissue planes, and fissures in the external ear canal can allow the spread of bacteria to the temporal bone, parotid gland, and the temporomandibular joint. Infection may also spread through the thin, osseous portion of the ear canal to the skull base. Patients with necrotizing external otitis complain of severe, unrelenting pain, often worse at night. Cranial nerve VII (facial) is the most commonly affected, leading to facial paralysis, although others may be involved (5,6).

Patients with AOM develop progressive pain as fluid accumulates in the middle ear, bulging the TM outward. There can also be hearing loss, vertigo, and low-grade fever. Perforation of the TM leads to drainage of pus or blood. This differs from otitis externa in that the pain improves after perforation and drainage occur.

Auricular cellulitis resembles soft tissue infections in other parts of the body. The ear is tender and erythematous in the absence of systemic complaints. Perichondritis is a deeper infection. Patients may present days to weeks after a high piercing. There is localized tenderness and possible purulent drainage and the ear may also appear deformed. The ear lobule is devoid of cartilage and is not involved in perichondritis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

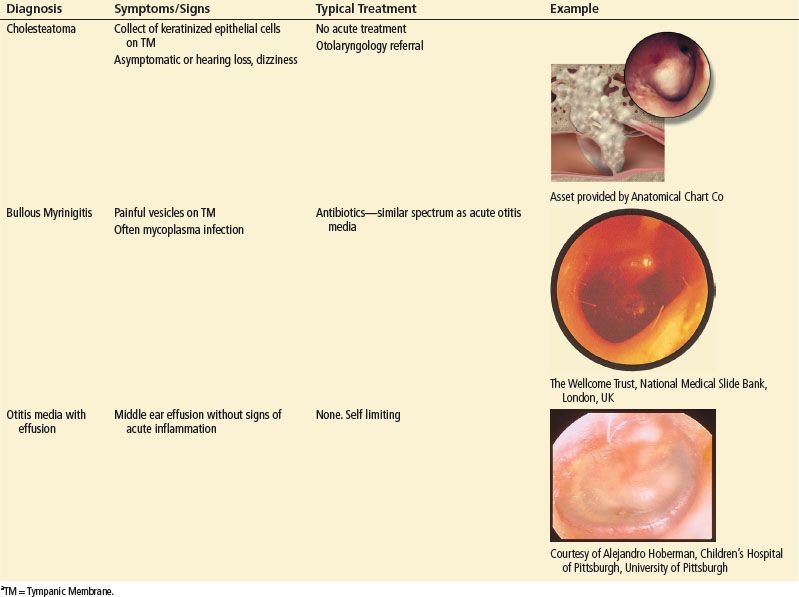

A variety of conditions can mimic otitis externa. These conditions may cause otalgia, otorrhea, and/or inflammation of the external ear canal. Commonly, otitis media with a perforation of the TM is misdiagnosed as otitis externa as a result of fluid drainage into the EAC. Chronic otitis media (COM) is defined as recurrent or chronic middle ear infections in the presence of a perforated TM, which may drain either serous or purulent fluid (i.e., chronic suppurative otitis media). Patients with COM have fluid drainage with less inflammation and tenderness of the external ear canal when compared with AOE. Cholesteatoma is a keratinized collection of epithelial cells diagnosed by its distinct appearance with patients being asymptomatic or presenting with hearing loss, dizziness and otorrhea. Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) presents with vesicles on the TM and adjacent tissues, otalgia and, classically, facial nerve palsy. Bullous myringitis, also characterized by small vesicles on the TM, is classically a manifestation of mycoplasma infection but occurs with other organisms as well. Localized abscesses also occur in the ear canal and are most often due to S. aureus. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external ear canal should be considered in an older patient who fails standard therapy for otitis externa. Fungal otitis externa should be considered if the physical examination shows a white or black discharge. Contact dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis are also mimickers of AOE.

A variety of disorders cause middle ear pain and may be confused with otitis media. Otitis media with effusion (OME) presents with a middle ear effusion without any signs or symptoms of acute inflammatory disease. Antibiotic therapy is not appropriate in these patients. COM, as described above, may also be mistaken for AOM. Frequently a cholesteatoma is also present. These patients need otolaryngology referral.

Relapsing polychondritis is an autoimmune disease that can involve the auricular cartilage in addition to the cartilaginous tissues in the respiratory tract and aorta. These patients present with complaints and physical examination findings similar to those of infective perichondritis. However, the ear lobe lacks cartilage and thus is spared in relapsing polychondritis.

ED EVALUATION

Acute Otitis Externa

Otitis externa is diagnosed based on history and physical findings. Patients should be questioned about predisposing factors such as water exposure, instrumentation of the ear canal, and immune status. The patient should be questioned about hearing loss, vertigo, and prior infections.

A thorough examination of the head and neck should follow. Patients almost invariably complain of pain with tragal manipulation or otoscope insertion. The ear canal is edematous and narrowed and may be filled with cellular debris. If possible, the external canal should be cleaned for better visualization of the deeper structures and to aid in treatment.

Patients with systemic toxicity should be evaluated for a deeper, invasive infection. The most common organisms are S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Patients with a chronically weeping, wet ear are more often infected with Pseudomonas. Staphylococcus tends to be associated with a more acute onset of symptoms. Appearance of granulation tissue on the floor of the EAC at the bony–cartilaginous junction is a typical finding in invasive disease. Although patients with invasive otitis externa may be in severe distress, they may remain afebrile with a normal white blood cell count (5,6). High-resolution, CT scan with thin cuts through the temporal bone, is generally the initial imaging study for patients with suspected invasive disease (6).

Acute Otitis Media

Patients with suspected AOM should also be asked about risk factors such as recent respiratory tract infections, a history of tobacco exposure (both primary and secondhand tobacco exposure increases risk), and barotrauma (e.g., air travel or scuba diving). To diagnose acute otitis media, the patient should have 1) acute symptoms, 2) a middle ear effusion, and 3) symptoms of middle ear inflammation. Classic findings (erythema and bulging of the TM) have been shown to be highly suggestive of disease, and a normal TM (one that is concave, gray, and translucent) is helpful in ruling out disease. To avoid overdiagnosis, pneumatic otoscopy is often recommended to confirm middle ear effusion; however this requires a cuffed speculum, and is often impractical in the emergency department. The physical examination should also focus on possible complications of otitis media. In addition to the ear itself, the mastoid process, nasopharynx, and oropharynx should be examined and a cranial nerve examination should be performed. If invasive infection or severe disease is suspected, CT scan with thin cuts through the temporal bone is the initial imaging study of choice (14). Contrast-enhanced CT scans or an MRI should be considered if one is concerned about intracranial complications. Note that fluid in the mastoid sinus found on imaging, radiologic mastoiditis, is a nonspecific finding and does not correlate with clinical mastoiditis since other diseases of the ear (AOM, COM, etc.) may result in fluid in the mastoid sinus (15,16). Laboratory tests are often not helpful in the initial examination.

Auricular Cellulitis and Perichondritis

The patient should be questioned about trauma and other exposures such as bites, as well as comorbid conditions. A careful inspection of the external ear is critical. One should also ask about previous history of similar episodes. The external ear structures should be palpated and any deformities or obvious abscesses noted. Early perichondritis can present as tenderness without erythema.

KEY TESTING

• Consider CT scan if invasive disease is suspected.