INTRODUCTION

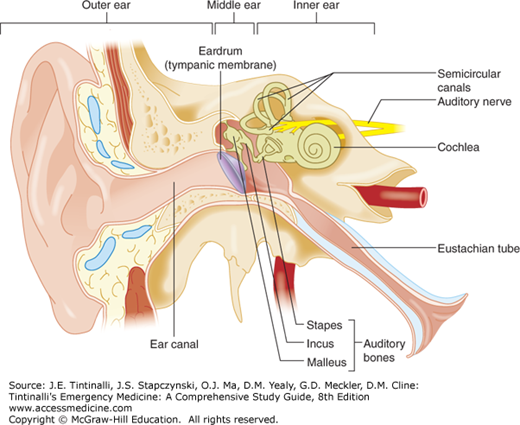

Ear pain, or otalgia, is one of the most common pediatric outpatient chief complaints. The differential diagnosis is listed in Table 118-1. This chapter discusses acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion, otitis externa, acute mastoiditis, and foreign body. Anatomically, the ear is divided into three major parts: (1) the outer ear, which includes the auricle and the external auditory canal; (2) the middle ear, which is bound by the tympanic membrane laterally, contains the auditory ossicles, and is connected to the nasopharynx via the eustachian tube; and (3) the inner ear, which includes the semicircular canals, the cochlea, and the auditory nerve (Figure 118-1).

Common

|

Less common

|

Rare

|

ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

Otitis media is a general term used to describe inflammation within the middle ear, and acute otitis media (AOM) specifically refers to the acute onset of signs and symptoms of middle ear inflammation. Otitis media is one of the two most common diagnoses for outpatient sick visits in children under 15 years old, accounting for 7.4% of all ED visits,1 and is second only to acute upper respiratory infection.2 However, visits appear to be decreasing due to a combination of increased financial barriers to care, improved public education regarding the viral nature of most infectious diseases, and the administration of contemporary pneumococcal and influenza vaccines.3

The peak incidence of AOM is between 6 and 18 months of age.4 In the United States, up to 50% of children will have had at least one episode of AOM by the age of 1 year.5 The incidence is higher in children who are Native Americans, Eskimos, males, day care attendees, exposed to tobacco smoke, born with craniofacial anomalies, prone position sleepers, pacifier users, or born with immunodeficiency syndromes.4,5 The incidence is also higher in infants who are diagnosed with their first episode of AOM before 6 months of age. Breastfed infants have a lower incidence of AOM compared to infants who are formula-fed.5

The middle ear is a laterally compressed cavity within the temporal bone bounded by the tympanic membrane laterally and the eustachian tube medially (Figure 118-1). In the healthy state, this space is aerated and contains the auditory bones, which transmit sound to the inner ear. Compared with adults, the eustachian tube in children is shorter and more horizontally oriented. This orientation is the anatomic rationale for the increased incidence of middle ear disease seen in children. An upper respiratory tract infection can obstruct the eustachian tube and disrupt its function of aerating the middle ear, creating conditions favorable to the development of sterile or purulent effusions.

Microorganisms responsible for AOM originate from the nasopharynx, enter the middle ear space via the eustachian tube, and include both bacteria and viruses. Both bacteria and viruses can be isolated in 66% of cases of AOM, bacteria alone in 27%, and viruses alone in 4%, and cultures are negative for both in 4%.6 The most common bacterial pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae (49%), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (29%), and Moraxella catarrhalis (28%). Common viruses identified in cases of AOM include picornaviruses such as rhinovirus and enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and parainfluenza virus.6

The classic symptom is rapid-onset ear pain. Young or nonverbal children may hold, tug, or rub the ear or be fussy and irritable. Fever is present in many but not all, although fever ≥40.5°C (104.9°F) is rare.7 Older children may complain of decreased hearing due to conductive hearing loss of middle ear effusion. An antecedent history of rhinorrhea, congestion, and/or cough is common because an upper respiratory tract infection creates conditions favorable to the development of AOM.

The most common acute complication is tympanic membrane perforation. More serious acute complications are rare and include mastoiditis, spread to the intracranial cavity (meningitis, encephalitis, abscess, sinus thrombosis, otitis hydrocephalus, facial or abducens nerve palsy), and involvement of the inner ear (labyrinthitis). Acquired sensorineural hearing loss can result from chronic or recurrent AOM and secondary inflammatory changes in the inner ear.

The diagnosis is clinical. Although tympanocentesis is the gold standard for diagnosis, it is outside the scope of most pediatricians and emergency physicians. Guidelines for clinical diagnosis are listed in Table 118-2.3 Erythema of the tympanic membrane alone is insufficient for the diagnosis of AOM because erythema can be caused by middle ear inflammation, crying, or fever.

| Scenario 1 | Moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane |

| Scenario 2 | Mild bulging of the tympanic membrane and at least 1 of the following: Acute onset of ear pain (<48 h) Intense erythema of the tympanic membrane |

| Scenario 3 | New onset of otorrhea not due to otitis externa or foreign body (indicating perforation of the tympanic membrane or AOM in a child with tympanostomy tubes) |

For proper otoscopic examination, use a bright light source, clean otoscope head, and properly fitting speculum. To immobilize the child’s head, have the caregiver hold the child’s head against the caregiver’s shoulder or chest. Or place the child supine with the examiner controlling the head of the child and the parents holding the child’s arms. Remove impacted cerumen with a soft speculum or by gently irrigating the canal with warm water. Both procedures can cause pain and/or traumatic perforation of the tympanic membrane and must be done carefully. Adjunctive use of a topical ceruminolytic agent such as docusate may be helpful in some cases.8

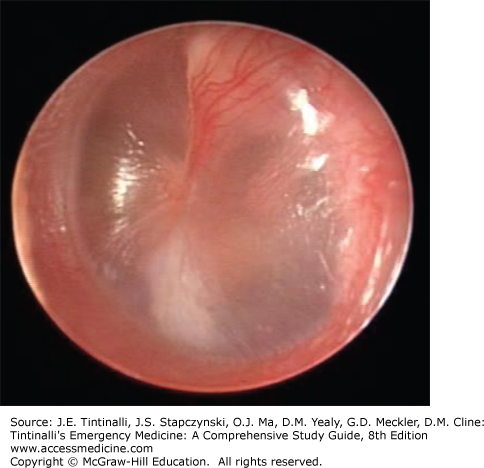

Assess for the presence or absence of discharge in the ear canal and the tympanic membrane’s position, color, degree of translucency, and mobility in response to positive and negative pressures created by the pneumatoscope. Table 118-3 and Figures 118-2 and 118-3 compare normal and abnormal tympanic membrane findings of effusion.

| TM Finding | Normal | Middle Ear Effusion |

|---|---|---|

| Position* | Flat | Bulging |

| Color | Pearly gray | Erythematous or hemorrhagic |

| Translucency | Translucent with easily discernable bony landmarks | Opaque without easily discernable bony landmarks |

| Mobility | Freely mobile | Decreased or absent |

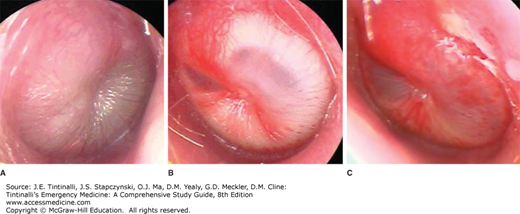

FIGURE 118-3.

Tympanic membrane findings consistent with acute otitis media. A. Severe bulging and opaque. B. Moderate bulging and opaque with intense erythema. C. Mild bulging with intense erythema. [Photos used with permission of Alejandro Hoberman, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.]

Most cases of AOM resolve spontaneously and without complications. Tympanic membrane perforation typically heals spontaneously after AOM resolution, but persistent perforations require ear, nose, and throat referral.

Antibiotics are recommended for some but not all cases of AOM.3 Pain control, however, is an essential treatment modality and should be provided whether or not antibiotics are prescribed.

The medications most commonly used to treat ear pain are shown in Table 118-4. Ibuprofen and acetaminophen are analgesic and antipyretics. Opioids medications such as oxycodone and hydrocodone may be considered for severe ear pain but should be reserved as second-line agents and used cautiously. Topical otic analgesic drops may be used in combination with systemic analgesics because they have a rapid onset and may provide temporary relief of ear pain but have a short duration of action.9,10,11 Topical analgesics are contraindicated in patients with perforation of the tympanic membrane and those with tympanostomy tubes.

| Medication | Comments |

|---|---|

| Systemic | |

| Ibuprofen (10 milligrams/kg PO every 6 h PRN) | First-line agents Also work as an antipyretic |

| Acetaminophen (15 milligrams/kg PO/PR every 4 h PRN) | |

| Oxycodone (0.1 milligram/kg PO every 4 h PRN) | Second-line agents Consider for severe otalgia Use cautiously due to side effects |

| Hydrocodone (0.2 milligram/kg PO every 6 h PRN) | |

| Topical | |

| Antipyrine/benzocaine (2–3 drops every 1–2 h PRN) | Apply drops to a small piece of cotton and place in external ear canal Provide rapid but short-term relief Contraindicated with perforation or tympanostomy tubes |

| Lidocaine (2% aqueous) (2–3 drops every 1–2 h PRN) | |

Consensus guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians recommend an initial observation option (defined as withholding immediate antibiotics) for select children with AOM.3,12 An observational approach for AOM has been used successfully in areas of Europe with similar rates of mastoiditis (the primary suppurative complication of AOM) compared to the United States,13 and this approach is now supported by several randomized controlled trials, systemic reviews, and observational studies.3 Tables 118-5 and 118-6 describe which children require initial antibiotics and which children can initially be observed without antibiotics.