Introduction

In this chapter, we assess available data on associations between irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and dyspareunia. IBS will be defined and a short summary of its characteristics provided. Sexual dysfunction (including dyspareunia) and chronic pelvic pain (CPP) will be discussed in the context of the well-recognized phenomenon of comorbidity between IBS and extra-intestinal unexplained symptoms and functional disorders. The chapter will conclude with a conceptual and mechanistic model and discussion of these associations.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the best known of the functional gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorders, all characterized by chronic or recurrent GI tract symptoms that are not explained by structural abnormalities, infection, or metabolic changes on routine testing [1, 2]. Patients with IBS suffer from chronic abdominal pain, usually in the lower abdomen, with an impaired bowel pattern. The latter can be constipation, diarrhea, or mixed constipation and diarrhea. Although the range of prevalence rates for IBS in studies conducted throughout the world is broad (from 2% to 25%), in the Western world, it is generally agreed that 10–20% of adults meet diagnostic criteria for IBS [1, 3, 4].

The burden of IBS on the health care services is substantial. As many as 28% of referrals for gastroenterology consultations are for IBS [5]. Absenteeism rates from work or school are significantly higher among patients with IBS than nonaffected individuals [6]. The cost of health services for patients with IBS is very high [7, 8].

Approximately 60–70% of IBS patients are women [6], making it a serious women’s health concern. The results of studies have shown that a greater awareness of IBS on the part of gynecologists could reduce the rate of unnecessary diagnostic tests and procedures in women complaining of pelvic/lower abdominal pain. Because of the similarity in pain of bowel and gynecological origin, the cause of women’s symptoms may be difficult to determine [9] and women with unrecognized IBS may undergo unnecessary pelvic laparoscopy or even surgery.

For many years IBS was considered a “diagnosis of exclusion.” However, over the past 20 years expert working groups have developed symptom-based, consensus-diagnostic criteria for IBS and the other functional GI disorders [1]. Known as the Rome criteria (Rome III in its latest version) (Table 21.1), these criteria have contributed to positive developments in the field of functional GI disorders. IBS can now be confidently diagnosed on the basis of a cluster of symptoms with a minimal diagnostic work-up [10].

IBS is a complex, multifactorial disorder. Research on the pathophysiology of IBS has focused on the bidirectionalsignaling pathways and information processing centers between the GI system and the central nervous system, known as the brain–gut axis [11–14]. The experience of abdominal pain and/or altered motility and bowel habits can be caused by impaired activity in the intestinal lumen, the intestinal mucosa, or the enteric nervous system [15–17].

Table 21.1 Rome III diagnostic criteria for IBS.*

| Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort** at least 3 days/month in the last 3 months associated with two or more of the following: |

| 1. Improvement with defecation; |

| 2. Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool; |

| 3. Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool. |

* Criterion fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

** “Discomfort” means an uncomfortable sensation not described as pain.

Brain–gut activity is mediated by biochemical factors incorporating input from the neuroendocrine and neuroimmunological systems [18]. Peripheral stressors and/or changes to the intestinal mucosa (e.g., following acute gastroenteritis [19, 20], transient mucosal inflammation, and/or prior abdominal or pelvic surgery [21–23] may affect afferent stimuli from the gut. A major factor in the experience of symptoms is abnormal central processing of peripheral afferent visceral signals, leading to a lowered threshold for pain (hypersensitivity) and increased selective attention to gut-related stimuli (hypervigilance) [24].

Similar processes have been implicated in “functional” gynecological disorders related to CPP and dyspareu-nia, including vestibulodynia. Pukall et al. reported that women with vestibulodynia have augmented sensory genital processing similar to other “hypersensitivity syndromes” such as IBS [25, 26].

Comorbid Conditions and Symptoms in IBS

In a systematic review of the literature, Whitehead et al. [27] reported that 50% of IBS patients complain of at least one other unexplained somatic symptom and that a significant number of IBS patients meet diagnostic criteria for other functional somatic syndromes [28] including CPP and dyspareunia.

When patients with IBS also suffer from other chronic unexplained symptoms (such as dyspareunia) and/or other non-GI functional disorders (such as CPP), there is a significant increase in symptom severity and comorbid psychopathology with a corresponding reduction in quality of life as compared to IBS patients without chronic comorbid conditions [27–29].

Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction Among IBS Patients

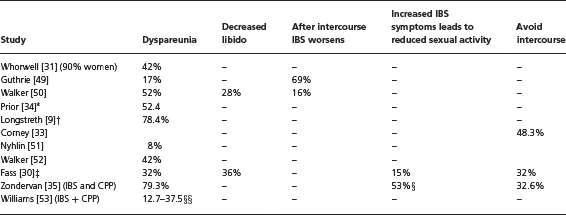

Some studies examine the link between IBS and dyspare-unia (Table 21.2), although there are more studies investigating the association between IBS and CPP. These studies have reported an increased prevalence of sexual dysfunction among IBS patients, including reduced sexual drive [30], increased dyspareunia [31, 32] and more severe IBS symptoms following intercourse. IBS patients report a high rate of intercourse avoidance [33]. The pres-enceofsexual dysfunctioninIBS maybeaffectedbyfactors such as a history of sexual abuse and disorders of the pelvic floor.

Whorwell et al. [31] assessed 100 consecutive IBS patients (90 women and 10 men) in the UK for noncolonic comorbid conditions in comparison with 100 controls matched to the patients by age, sex, and social class. Among the IBS patients, 42% reported dyspareunia compared to 5% of the controls (P < 0.0001). This significant association was not affected by the presence or absence of psychological comorbidity. In contrast, there was no significant difference between the groups in the percentage reporting premenstrual tension (63% and 55%, respectively).

Prior et al. [34] evaluated 798 patients referred by general practitioners to a gynecological clinic over a 6-year period. Of these, 63 were referred for dyspareunia of whom 52.4% were found to meet diagnostic criteria for IBS (40.8–59.2, 95% CI, P < 0.001). This strong association was not related to overlap with other indications for referral to the gynecology clinic. Interestingly, the prevalence of IBS was particularly high among women complaining of dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea, but was similar to rates for controls in women who came to the gynecology clinic for other indications such as termination of sterilization, for cervical abnormalities, and because of prolapse, cysts, or vulvar warts.

Longstreth et al. [9] assessed 86 women undergoing gynecological laparoscopy for CPP. IBS was diagnosed in 47.7% of these women. Those with IBS were compared with those without IBS on a series of demographic and clinical variables as well as findings at laparoscopy. No significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of age, symptoms (pain duration, abnormal menstrual bleeding, depression, chronic headache or backache), or findings on laparoscopy (adhesions, endometriosis, functional ovarian cyst, uterine fibroid, chronic PID, neoplastic ovarian cyst, or other findings). However, there was a significant difference between the groups in rates of dyspareunia. Among women with IBS, 78.4% complained of dyspareunia compared with 53.8% among those without IBS (P < 0.05).

Table 21.2 Reported rates of dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction in women with IBS, with and without CPP.

‘Women with dyspareunia who were diagnosed with IBS

†Women with CPP and IBS referred for diagnostic pelvic laparoscopy

‡Women with IBS and a sexual problem over previous 6 months

§IBS, CPP, and genitourinary symptoms

§§Mixed dyspareunia = 12.7%; functional = 11.8%; organic, 37.5%

Zondervan et al. [35] conducted a community-based survey of a representative sample of women in a district of England examining the overlap among CPP, dys-menorrhea, dyspareunia, and IBS. Among women with CPP without IBS, 41% reported dyspareunia over the previous three months (compared with 13.8% among women without either CPP or IBS). The percentage of women reporting dyspareunia increased to 79.3% among women who reported CPP and IBS. Another finding of interest was that among women with CPP without IBS, 22% reported having sexual intercourse less frequently because of the pain compared with 53% among women with CPP, IBS, and genitourinary symptoms (P <

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree