Dizziness

Jonathan A. Edlow

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Dizziness is one of the most common presenting symptoms in emergency medicine (1,2). Misdiagnosis is common, even when patients are evaluated by neurologists (3). Dizziness has numerous causes and the very word “dizziness” means different things to different people. Older dizzy patients, who are becoming increasingly common in the emergency department (ED), have a higher incidence of serious central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular causes (4–6). Furthermore, dizziness is often caused by a variety of non-CNS or cardiovascular symptoms such as toxic-metabolic and infectious disorders. For all these reasons, correct diagnosis is important, but can be challenging. The evidence base for our understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of dizziness is weak (7), but has increased substantially in the past several years (8,9).

The traditional diagnostic approach to dizziness is based on “symptom quality,” a paradigm that was first published in 1972, based on limited data from a small number of selected patients evaluated in a specialty clinic (10). The “symptom quality” method is to ask the patient, “What do you mean dizzy?” and their response will place them into one of the four categories: vertigo, presyncope, disequilibrium, or “other” nonspecific dizziness. Implicit is that each category has etiologic significance: Vertiginous patients have vestibular causes (usually peripheral), presyncopal patients have cardiovascular causes, those with disequilibrium have neurologic issues whereas nonspecific dizziness is caused by psychiatric disease.

The “symptom quality” approach has fundamental problems. The first has to do with the methods of the original 1972 paper (10). Methodologic weaknesses include small number of patients enrolled, diagnosis assigned by a single neurologist without independent verification, no brain imaging nor any long-term follow-up. Furthermore, some diagnoses known now to be common causes of dizziness (e.g., vestibular migraine), had not yet been recognized as diagnostic entities. Nevertheless, when no tests identified a specific diagnosis, the type of dizziness was used to assign the final diagnosis (e.g., vertigo was assigned a peripheral vestibular cause if no other cause was found). The paradigm of “symptom quality” has never been prospectively and properly validated.

Most ED dizzy patients would never end up in an outpatient specialist-run dizziness clinic, including those with acute cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic, infectious, and other causes. The original study was done in an era of fewer medications (propranolol was the only beta-blocker, there were many fewer antihypertensive agents) and far less polypharmacy. Thus, the patients in that 1972 study were not at all representative of patients seen in an ED in 2014.

Sensory symptoms are difficult to describe. A recent study asked patients a series of questions designed at describing their dizziness type (11). Within 10 minutes, they were asked the same questions but given the answer choices in a different sequence. Half the patients changed the category of dizziness that they had initially endorsed just a few minutes before, and most endorsed multiple dizziness symptom qualities. This fact alone seriously undercuts the “symptom quality” paradigm.

Other recent research shows that patients with cardiac causes of dizziness often use the word “vertigo” to describe what they are feeling (12). In another study of older patients presenting to an ED with dizziness, the use of the word “vertigo” (as opposed to lightheadedness or dizziness) did not predict those who had a cerebrovascular cause (13). The converse is also true. Patients with clear-cut vestibular disease often complain of vague lightheadedness or nonspecific “dizziness.”

Taken together, this literature suggests that using the “symptom quality” paradigm for the diagnosis of unselected dizzy patients has serious shortcomings. As well, they begin to suggest an alternative paradigm based on “timing and triggers.” In the study showing that patients change their “type” of dizziness, their responses to issues about dizziness timing and triggers were far more reliable (11). Because the type of dizziness may not be etiologically useful and because many of the major dizziness syndromes have reliable timing and triggers patterns, an alternative paradigm based on “timing and triggers” may be more useful to the clinician.

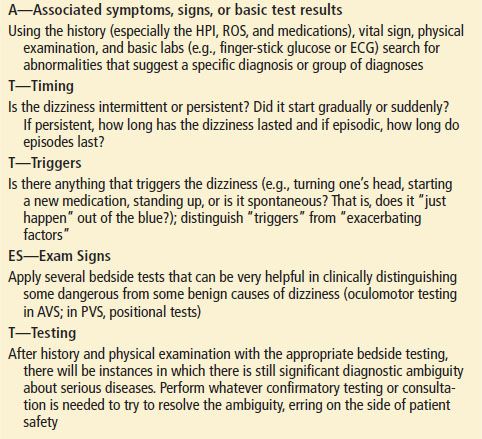

The “timing and triggers” paradigm can be summarized using the mnemonic of ATTEST (see Table 14.1).

TABLE 14.1

Attest—A Method for Diagnosing Dizzy Patients

A: Associated symptoms, signs, and basic testing (such as finger- stick glucose)

TT: Timing and Triggers

ES: Exam Signs

T: Testing (if needed to confirm the clinical diagnosis)

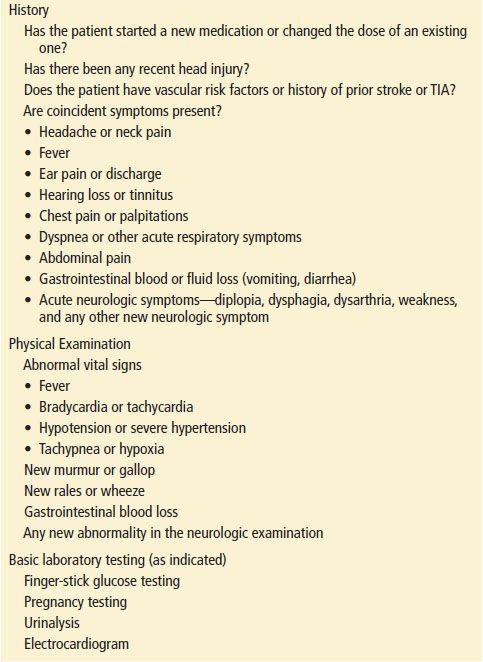

First, the emergency physician (EP) should ask about associated symptoms that suggest a particular diagnosis or group of diagnoses (Table 14.2). For example, dizziness associated with chest pain, or vomiting and diarrhea, or acute neck pain, or fever and cough, suggest obvious possible diagnoses. Has the patient started a new medication? It is important to establish what symptoms accompany the dizziness since a large proportion of ED patients have various medical (and not vestibular or neurologic) problems that cause their dizziness (4). This step will often lead to a clear-cut limited differential diagnosis and workup for many patients (e.g., a chest x-ray for a dizzy patient with fever, cough, and green sputum).

TABLE 14.2

Associated Findings (That May Suggest a Specific Diagnosis or Group of Diagnoses)

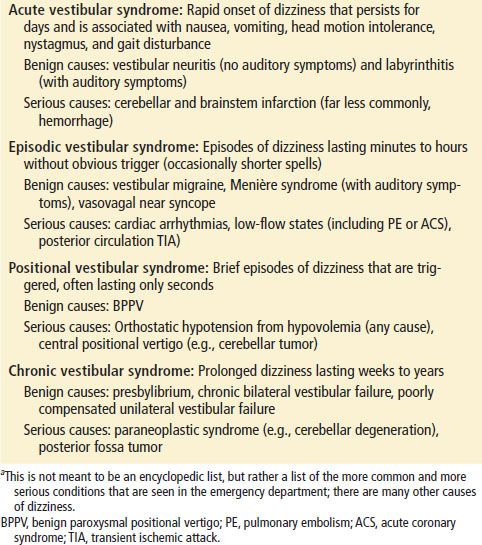

Next, the EP should ask questions designed to place the patient into one of four “timing and triggers” categories (see Table 14.3). These include the acute vestibular syndrome (AVS), the episodic vestibular syndrome (EVS), the positional vestibular syndrome (PVS), and the chronic vestibular syndrome (CVS). The history can be used to define the onset, duration, constancy, and triggering or exacerbating features. Patients can generally describe these features of their histories more reliably than the “type” of dizziness (11). Each of these four categories suggests a particular differential diagnosis (see Differential Diagnosis section and Table 14.3).

TABLE 14.3

Timing and Triggers Categories for Dizzy Patients (and Differential Diagnosis of More Common Causes)a

Once the category is defined, then one uses bedside and other routine tests to further narrow the differential diagnosis. Some of this testing is part of a normal physical examination. Is the patient mentating normally? Is there obvious nystagmus on primary gaze (staring straight ahead)? Is there a murmur or signs of heart failure? Is there melena or evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding? Some of the confirmatory tests are a more detailed bedside oculomotor examination that helps to distinguish central from peripheral vestibular disorders. These tests are easy to learn to do and interpret.

Confirmation with more sophisticated (nonbedside) tests is the final step. This might mean a computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest if pulmonary embolism (PE) is the target diagnosis or telemetry, serial cardiac enzymes, and electrocardiograms if an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the concern. Many patients will not need these tests because the bedside examination findings and basic tests can establish some diagnoses (e.g., vestibular neuritis or benign paroxysmal positional vertigo or a urinary tract infection).

The “timing and triggers” paradigm frequently leads to making a specific diagnosis compared to the traditional “symptom quality” approach. The approach to patients with AVS and PVS have been studied fairly extensively (8,9,14), but it is important to acknowledge that the “timing and triggers” or ATTEST approach has not been prospectively validated or systematically studied.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Without some type of diagnostic strategy or algorithmic approach, diagnosis of the dizzy patient is an exercise in futility since dozens, if not hundreds, of individual conditions as well as side effects from nearly every medication can produce dizziness. An approach based on “timing and triggers” also suggests a differential diagnosis based on various temporal categories (Table 14.3).

For patients with an AVS, the major differential diagnosis is a peripheral vestibular process (of the eighth nerve or its end organ) versus stroke. The eighth cranial nerve has two components, the vestibular and the cochlear, that can be affected together or individually. Patients with vestibular neuritis have dizziness (but no hearing loss) (15). Patients with acute sensorineural hearing loss have diminished hearing (and no dizziness) (16,17). The term labyrinthitis is often used when both systems are affected. Because the organs of balance and hearing are colocated peripherally, coinvolvement of dizziness and hearing generally implicates a peripheral process, but there is an important exception.

The labyrinth is supplied by the labyrinthine artery, which is a branch of the anterior-inferior cerebellar artery (AICA—itself originating from the basilar). It is, therefore, possible that an AVS or an acute sensorineural hearing loss is due to a stroke. This is probably less common than benign peripheral causes; however, with AICA strokes, both balance and hearing are usually affected (18). Although “vertigo” has been reported in patients with supratentorial stroke (19), patients with dizziness or vertigo as a prominent presenting symptom of cerebrovascular disease usually have posterior fossa strokes (20). Although vestibular neuritis accounts for the majority of patients who present with the AVS, cerebellar (or brainstem) stroke is the other important possibility that is critically important for the emergency physician to consider (21). Bedside testing can help distinguish between these groups of patients, and within the first 48 hours, may actually be better than MRI (14).

Acute intracerebral hemorrhage is a very rare cause of the AVS; almost all such patients have other neurologic symptoms or signs (22). Some older patients with a toxic–metabolic or infectious problem could present with an AVS but the frequency with which this happens is probably low (<1%) (9) and many of these patients will likely be identified by attention to associated symptoms. Multiple sclerosis can also present as the AVS.

Vestibular migraine is the most common cause of the EVS. Migraine is extremely common in the general population and in one series of dizzy patients older than 65 years, 13% were found to have vestibular migraine (23). However, the EP should be cautious in diagnosing migraine in elderly patients without a prior history of migraine. Dizziness from migraine can occur with or without headache (24). Duration of attacks is often minutes to hours to days but can last seconds in 10% of patients (24). Head motion intolerance is common (24). Meniére disease is another cause of the EVS and is associated with episodic dizziness and hearing loss, tinnitus and ear fullness that last between minutes and hours (25). Meniére disease is an uncommon cause in the ED.

The major serious diagnoses that present with the EVS are transient ischemic attack (TIA) of the posterior circulation, cardiac arrhythmias, and transient low flow states such as from a PE, an ACS, or aortic stenosis. As for posterior circulation TIA, classic teaching is that other brainstem symptoms are nearly always associated with dizziness, at least in patients presenting with episodes occurring over more than 3 weeks (26). Since 1975, when the NIH published its TIA classification system (27), many authorities have recommended this definition, which stated that patients presenting with isolated vertigo, general dizziness, diplopia, and dysarthria should not be diagnosed with posterior circulation TIA. Several authors report that TIA can present with isolated dizziness (28–30). Others have reported that spells of dizziness (even over months) can herald a subsequent basilar stroke (31). More recent data clearly suggests that the symptoms above (formerly thought not to represent TIA) in fact do (32). Patients presenting with these symptoms had an odds ratio of 15 for having a vertebrobasilar territory stroke, many within the 48 hours following the transient neurologic symptoms (32). Some of these patients had isolated vertigo. Patients with vertebral stenosis and posterior circulation symptoms are at particularly high risk for subsequent stroke (33).

Patients with the PVS have a narrower differential diagnosis. BPPV is the most common benign cause. These patients have very brief episodes lasting about 15 to 30 seconds that are triggered by head movement. It is important to note that many episodes occur at night in bed and therefore some patients have difficulty precisely fixing the duration of the spells. This is one instance in which a symptom waking a patient from sleep makes a benign diagnosis more likely than a serious one. Patients with BPPV may feel an anticipation of dizziness and will sometimes report “constant” dizziness for days, but a careful history will tease out the true episodic nature of the dizziness. It is important to note that many patients with BPPV do not endorse true vertigo (34). As well, BPPV may be less well recognized in elderly patients (35). It bears reemphasis that these patients may complain of vertigo or vague lightheadedness or dizziness that can easily be mistaken for orthostasis if symptoms occur on arising in the morning, as is often the case. The two can usually be distinguished, however, by inquiring whether the symptoms also occur on reclining or rolling over in bed, which should not occur in those with orthostatic hypotension.

More serious diagnoses that present as the PVS include orthostatic hypotension of any cause and central positional vertigo. The former can be due to any dangerous cause of hypovolemia such as gastrointestinal bleeding, fluid losses from gastroenteritis, persistent vomiting, and others including medication side effects (36). Abnormal orthostatic vital signs are very common in elderly patients especially in those who live in extended care facilities (37); this means that orthostasis is a common cause of dizziness, but also that the presence of an orthostatic blood pressure drop may be an incidental finding in an elderly patient with dizziness of another cause.

Central positional vertigo is a very uncommon BPPV mimic that can be caused by tumors, strokes, and other CNS lesions (38–40). Most of these patients will have physical examination clues during positional testing (Dix–Hallpike) that typical BPPV is not the correct diagnosis: persistent symptoms or signs lasting longer than 1 minute, downbeat nystagmus, lack of latency to nystagmus onset, and lack of therapeutic response to an Epley or other canalith repositioning maneuver (41).

Patients with the CVS whose symptoms persist longer than weeks most commonly have polysensory dizziness, degenerative neurologic disease, psychiatric syndromes, drug side effects, or drug–drug interactions, although specific data about the relative frequency for various causes are lacking. Occasionally, a patient with a slow growing posterior fossa tumor can present with the CVS.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History

The history is of paramount importance. In addition to the usual history, the following steps may help focus and supply clues that may help pinpoint a diagnosis or at least help to narrow the list of potential diagnoses.

The ATTEST (Table 14.1) mnemonic should be used to gather the important elements of the history. Associated symptoms should be identified that may supply clues of the underlying etiology (see Table 14.2). Antecedent medication changes or head trauma may suggest a drug side effect or posttraumatic BPPV. The clinician’s focus will be different with a patient who presents with severe abrupt onset headache with dizziness than with a dizzy patient who reports abdominal pain and diarrhea as associated symptoms.

A distinction should be made between “triggering” the dizziness and “exacerbating” the dizziness. “Triggered” dizziness suggests that something made a patient dizzy when they started out not dizzy. An example is a patient who is lying on a stretcher completely asymptomatic and when a Dix–Hallpike is done, the patient becomes dizzy. “Exacerbated” suggests that something increased a dizzy patient’s symptoms (but they were already dizzy to start with). An example of this would be a patient with vestibular neuritis who feels dizzy at baseline while lying still in the stretcher, but on head motion, the dizziness intensifies.

This is a very important distinction and highlights a common misconception about dizziness (42). The misconception is that a patient whose dizziness worsens with head motion has a peripheral vestibular cause of their dizziness. This is not true. A dizzy patient from a stroke, multiple sclerosis, or a cerebellar tumor, will develop worse dizziness with head movement. A hypovolemic patient will also have worse dizziness upon changing position (standing up).

Next, a “timing and triggers” category should be defined by asking questions such as the following.

• “When did the dizziness start?”

• “Did it begin suddenly or gradually?”

• “What were you doing when it started?”

• “How long does the dizziness last?”

• “Is it episodic or continuous?”

• “If it’s episodic, how long do episodes last?”

• “Are the episodes triggered or do they occur without warning?”

• “If they are triggered, what seems to be the trigger?”

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination of the dizzy patient needs to be fairly comprehensive given the long list of possible causes but always starts with considering the vital signs (factoring in the specific chief complaint). For example, if a patient has dizziness with a new fever, then the source of the fever should be sought. If the fever is associated with cough, then a chest x-ray is likely indicated. Dizziness and tachycardia should raise the suspicion of a gastrointestinal bleed or PE or perhaps just dehydration from poor PO intake as a result of a vestibular disorder.

The EP should not pigeonhole the patient too early in the evaluation and certainly not based on which word the patient uses to describe their dizziness. A patient endorsing true vertigo “like the room is spinning around” might have rapid atrial fibrillation whereas another patient complaining of “lightheadedness” might have BPPV. With the caveat that the physician has done relatively thorough general and cardiac examinations and that the vital signs do not suggest anything obvious or catastrophic, special care should be taken on the examination of the ears, eyes, and nervous system. As for the neurologic examination, the EP should test the gait, and focus on the cerebellar and oculomotor examinations.

The tympanic membrane is inspected for signs of otitis. Unilateral new hearing deficit plus dizziness suggests a peripheral cause, since hearing and balance end organs are colocated peripherally. However, in the appropriate setting (abrupt onset of symptoms in a patient with vascular risk factors), a stroke involving the AICA or its labyrinthine branch can cause acute hearing loss and dizziness.

Gait should be tested. Patients who normally use a cane or a walker should be tested using those devices to allow for a meaningful comparison with their baseline. A new gait abnormality, especially the inability to walk without falling, should suggest a central cause of dizziness or severe volume depletion. In a patient who is vomiting, having the patient try to sit up in the stretcher without holding on to the side rails (e.g., with arms crossed across the chest) will also test for truncal ataxia. In patients with the AVS, presence of severe gait instability or truncal ataxia strongly suggests a CNS cause (21,43).

As well, in patients with the AVS, three specific bedside oculomotor tests can identify posterior circulation stroke more accurately than MRI, at least in the first 48 hours from symptom onset (14). These three tests are the horizontal head impulse test (HIT), testing for direction-changing gaze-evoked nystagmus, and alternate cover test for skew deviation (14). An important caveat to this study is that it was done by trained neuro-otologists. However, from the perspective of a practicing emergency physician, these tests are relatively easy to learn to perform and interpret. In patients presenting with an AVS, the presence of any of the worrisome findings suggests stroke (or another central cause) whereas the absence of all the worrisome findings strongly suggests a peripheral problem.

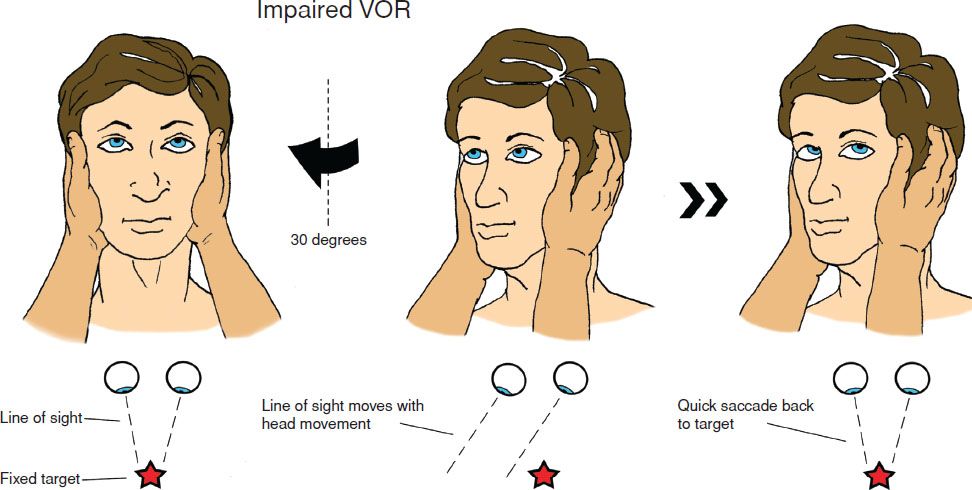

The HIT was first described in 1988 (44). Figure 14.1 shows how the test is performed and interpreted. The presence of a corrective saccade of the eyes back toward the examiner’s nose is a positive test and means that the lesion is likely in the peripheral labyrinth. The maneuver tests the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), which does not loop through the cerebellum or lower brainstem, that is why it is negative (no corrective saccade) in patients with cerebellar or medullary strokes. Pooled results across four studies identified as part of a systematic review showed that a normal HIT was found in 85% of patients with stroke (n = 152) and only 5% of patients with a peripheral vestibular problem (n = 65) (9). However, the HIT will be positive in some patients with brainstem stroke that affects the vestibular nerve root entry zone in the pons. Most patients with these brainstem strokes will have one of the other two eye findings on examinaton that indicates the central nature of the lesion (14). The HIT is a safe test although a single case of transient complete heart block has been described (45).

FIGURE 14.1 The head impulse test (HIT, sometimes referred to as the head thrust test) is a test of vestibular function that can be easily done during bedside examination. The HIT tests the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), and can help to distinguish a peripheral process (vestibular neuritis) from a central one (cerebellar stroke). With the patient sitting on the stretcher, the physician instructs him to maintain his gaze on the examiner’s nose. The physician holds the patient’s head steady in the midline axis and then rapidly turns the head to about 20 degrees off the midline. Panel 1: The normal response (intact VOR) is for the eyes to stay locked on the examiner’s nose. Panel 2: The abnormal response (impaired VOR) is for the eyes to move with the head, and then to snap back in one corrective saccade to the examiner’s nose. The HIT is usually “positive” (i.e., a corrective saccade is visible) with a peripheral lesion (vestibular neuritis), and the test is normal (no corrective saccade) in cerebellar stroke. This occurs because the VOR pathway does not loop through the cerebellum. Occasional patients with small brainstem strokes may have a positive test because the VOR pathway does loop through the brainstem. Because it is the “positive” test that is reassuring with the head impulse test and the “negative” test that is worrisome, it is very important to only use the test in patients with the AVS. If one were to use the HIT in patients with pneumonia or with a fractured wrist, the HIT would be “negative” (worrisome for a CNS event). Therefore, it is critical that it only be applied to patients presenting with an AVS.